What’s the Best Way to Structure a Joint Venture?

The advantages JVs offer can come with challenges that make joint venture agreements more difficult to negotiate.

Negotiations to form or terminate a joint venture can stall – sometimes indefinitely – for many reasons.

Chief among them is disagreement on valuation – whether the relative value of the parties’ assets contributed into the venture at inception, or the current value of the venture’s projected performance at break-up.

Disagreements on valuation are, in essence, divergent assumptions about the future: how the parties’ contributions to the venture will perform, what the venture as a whole will accomplish, and how the external market (including prices, costs, and regulation) will evolve.

Contingent deal terms are one way bridge these differences. Under a contingent term, if certain events or outcomes occur (for example, growth milestones, performance targets, price levels, regulatory decisions), then a particular action is automatically triggered[1]See, Managing the Future with Contingent Deal Terms, The JV Deal Exchange Issue 13, Water Street Partners.

The pharma and biotech industry is no stranger to contingent deal terms. Milestone payments and tiered royalties in pharma and biotech partnerships are almost always tied to R&D and commercialization targets. Upstream oil and gas and mining exploration partnerships also use contingent terms extensively. Companies in these sectors for instance, earn into ventures based on how much they spend.

But beyond these industries, contingent terms have been underutilized in joint ventures.

That was until last year. And then things changed.

With rising inflation and interest rates, and general uncertainty around the profitability and expected return of joint venture investments – especially in green energy – contingent deal terms are now suddenly a prominent feature of many venture agreements[2]The use of earnouts – a contingent term used in M&As – has also been on the rise in M&A transactions over the past year as a hedge against uncertainty. See, Companies Turn to Earnouts to … Continue reading.

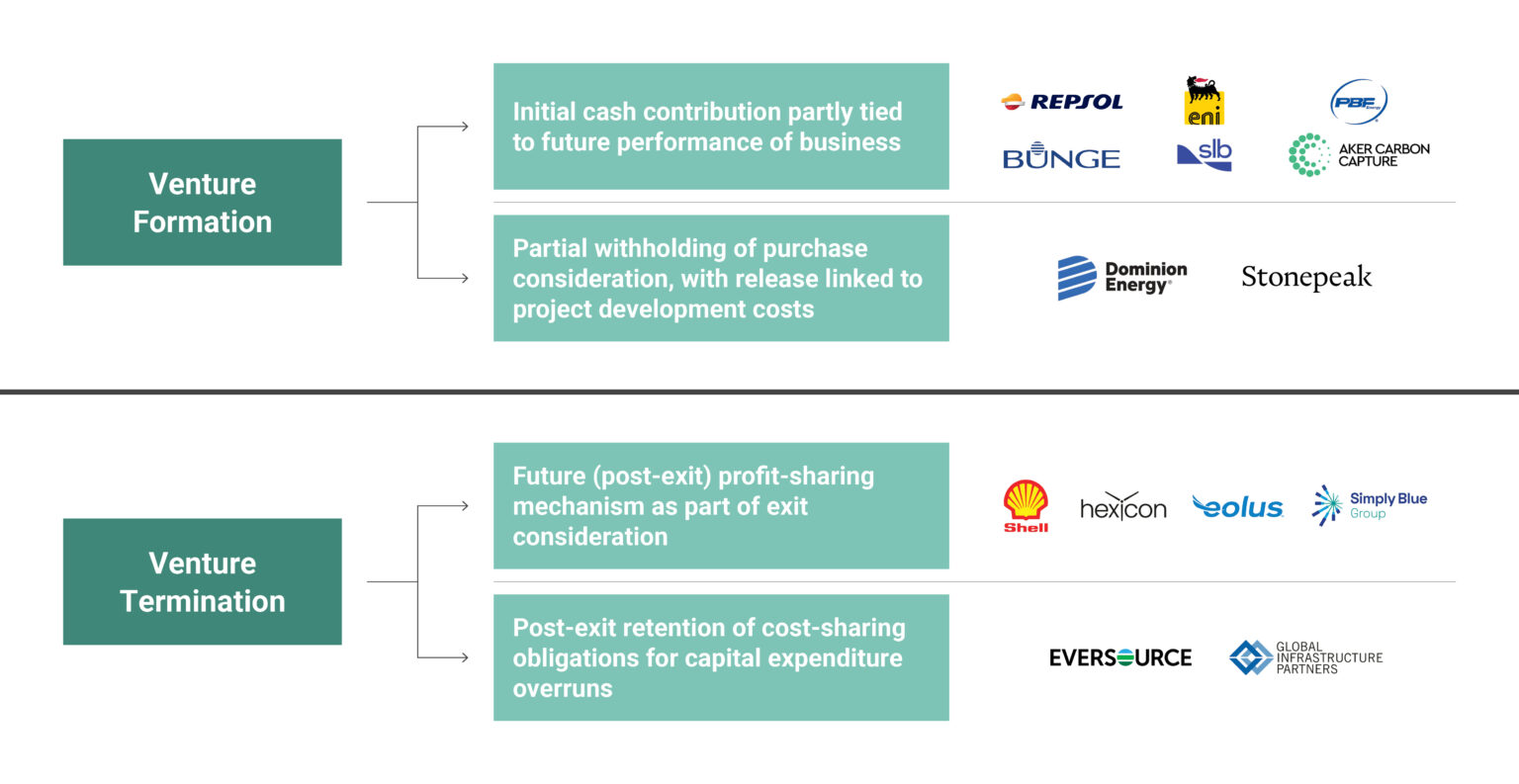

Companies are using different types of contingent deal terms in their green energy joint ventures. At venture formation, companies are either tying part of their initial cash contribution to the performance of the assets or business contributed by their partner, or to development costs of the venture’s project. At termination, companies are either negotiating for a post-exit profit-sharing mechanism or payout, or a post-exit retention of obligations to meet cost overruns (Exhibit 1).

Source: Publicly available information; Ankura analysis

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

A few of these deals are illustrated below:

Contingent deal terms might seem like an ideal solution to circumvent gridlock in the heat of negotiations.

But drafted incorrectly these terms may just push disagreements to the future.

Retailer Marks & Spencer’s dispute with its partner Ocado is a cautionary tale in avoiding triggering conditions that are ambiguous. Under the deal, Marks & Spencer signed a £750 million ($949 million) deal in 2019 to own half of Ocado Group’s retail business. The retailer agreed to pay Ocado an initial £562 million ($710 million) upfront and make another payment of around £190 million ($240 million) if the venture met certain performance targets. Marks & Spencer believes that the final payment is binary – that is, it must pay the sum in full if the targets are met, or not at all. And since the venture missed the set targets, it is justified in withholding the payout. On the other hand, Ocado believes that the contract allowed for the targets to be adjusted – and that certain decisions jointly made by the partners over the past few years met the requirement for adjustment. Ocado is now threatening to sue Marks & Spencer to receive the payment in full.

In addition to avoiding language that can be interpreted differently, another obvious pitfall that dealmakers need to avoid is trigger conditions that can be gamed by one party for its advantage. For instance, if a payout to one party is linked to the performance of an asset, but its counterparty’s actions or inactions are critical to the optimal performance of the asset, then the contingent term should be avoided altogether – or used cautiously with a mitigating provision against the counterparty’s actions or inactions in bad faith.

Pitfalls aside, there are some enhancements that can be considered in drafting contingent terms.

One of which is the ability to settle the contingent payout earlier than it is due – when for instance, market conditions are expected to change unpredictably and a party does not want to hold on to a potentially unpredictable liability or alternatively, is willing to settle earlier. Miner Newmont’s exit from PT Newmont Nusa Tenggara (PTNNT), operator of the Batu Hijau copper and gold mine in Indonesia had such an enhancement. Newmont received a total consideration of $1.3 billion for its 48.5% economic interest in PTNNT. This amount comprised gross cash proceeds of $920 million and contingent payments of $403 million tied to, among other factors, higher copper prices in the future. This “metal upside amount” was payable to Newmont in any quarter – over a particular production phase of the venture – in which the London Metal Exchange quarterly average copper price exceeded a set amount. But the contract also provided for the parties to arrive at a settlement amount – and terminate the contingent payment – at any time after the first anniversary of the agreement by appointing two independent financial institutions to determine the current value of the “metal upside amount”.

Another possible enhancement is providing for a dispute resolution process – including binding arbitration – to settle any future disagreements, especially on whether, and the extent to which, the trigger condition has been fulfilled and a payout is required.

With the surge and swell of economic and regulatory uncertainty showing no sign of abating, is a contingent term right for your next joint venture?

We understand that succeeding in joint ventures and partnerships requires a blend of hard facts and analysis, with an ability to align partners around a common vision and practical solutions that reflect their different interests and constraints. Our team is composed of strategy consultants, transaction attorneys, and investment bankers with significant experience on joint ventures and partnerships – reflecting the unique skillset required to design and evolve these ventures. We also bring an unrivaled database of deal terms and governance practices in joint ventures and partnerships, as well as proprietary standards, which allow us to benchmark transaction structures and existing ventures, and thus better identify and build alignment around gaps and potential solutions. Contact us to learn more about how we can help you.

Comments