It’s time to address the ESG paradox. Our focus on the “E” in ESG may be coming at the expense of the “S”. We can mitigate this impact, and mining joint ventures will be key.

The mining value chain is foundational to the world’s transition from fossil fuels. Clean energy technologies depend on minerals like nickel, lithium, copper, and cobalt, as well as rare earth elements, and the World Bank estimates that production of these minerals could increase by nearly 500% by 2050 to meet growing demand for clean energy technologies. However, in the search for the raw materials needed for clean energy technologies, we must not overlook the human rights, labor, land, and water contamination impacts caused by mining. Strip mining, for example, takes up significant areas of land that rural communities depend upon for their livelihood, and runoffs contaminate farmland and watersheds and negatively impact both water quality and quantity. Meanwhile, the search for rare earth elements is driving mining activities into more remote parts of the world, impinging on traditional communities.

The impact is already being felt around the world: Chile, the world’s second-largest lithium producer, has drafted a new constitution that includes sweeping new protections for the environment and broadens the ability for ordinary Chileans and indigenous groups to safeguard the environment, especially with respect to water management. In Serbia, the government canceled Rio Tinto’s license to develop a lithium mine in response to weeks of protests about the damage the mine will cause to farming land and watersheds.

Fortunately, investors, regulators, and civil society are beginning to recognize that corporate ESG performance cannot be a zero-sum game. Tesla, Apple, and other leading industrial and technology companies have made public commitments to responsibly source minerals. In addition, many European countries have enacted supply-chain due diligence laws to ensure that mineral supply chains avoid contributing to serious human rights abuses and conflict. But complex global supply chains means many companies and regulators, despite their best efforts, have limited ability to scrutinize the human rights impact of mining. This opens the door to operational, financial and legal risks for clean energy technology companies.

The Joint Venture Trap

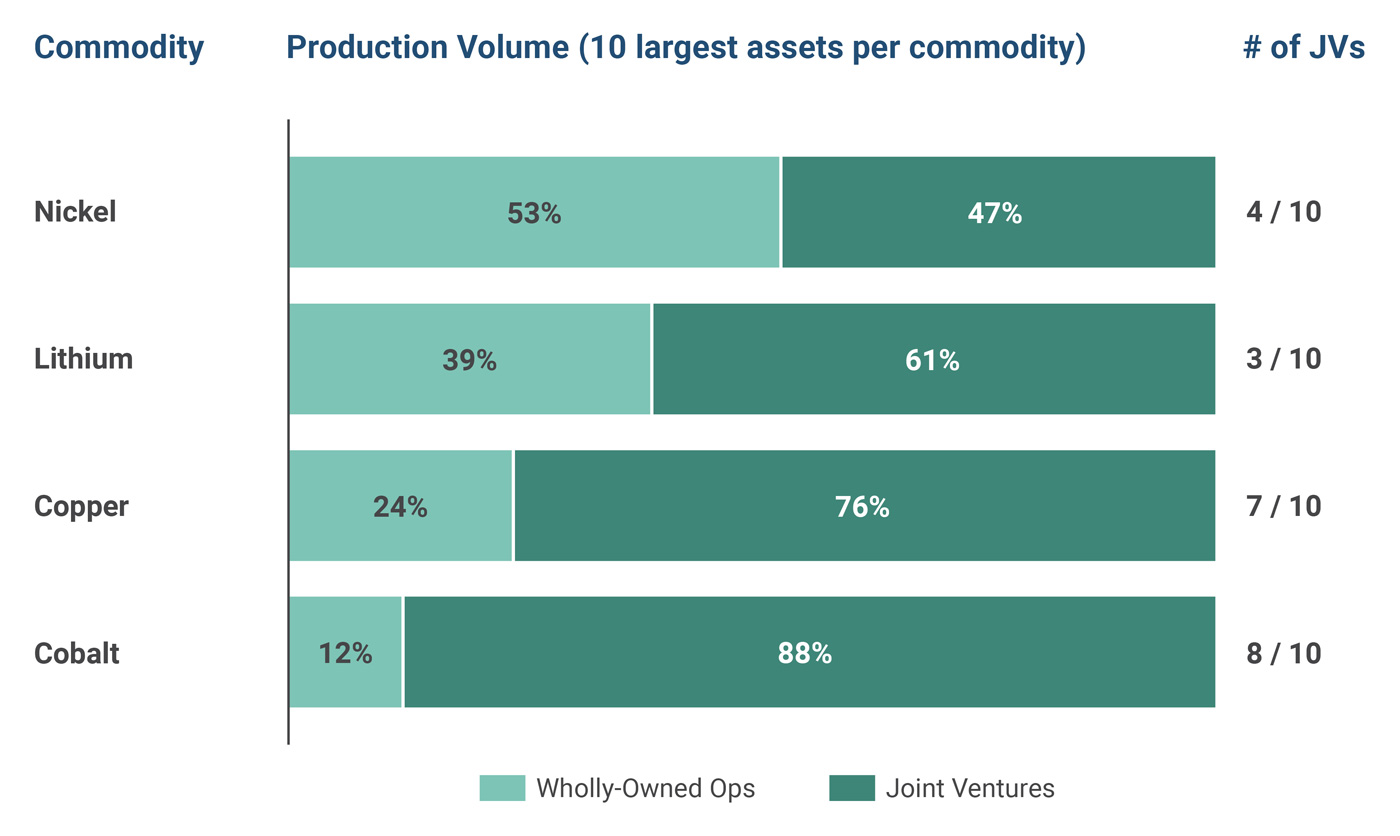

Implementing good human rights practices in the mining industry often must be done through joint ventures. More than half of the current production of key commodities that are critical to a more sustainable future comes from joint ventures (Exhibit A). What’s more, the world’s leading publicly-listed mining companies – e.g., Rio Tinto, BHP, and Vale – hold portfolios of 20 or more joint ventures, many of which are non-operated minority investments. This ownership construct makes it more difficult to ensure – and historically insulated companies from demanding – that such operations adopt strong human rights and social management practices.

Exhibit A: Importance of JVs in Mining

Source: Ankura Metals & Mining Database 2021, S&P Global Market Intelligence

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

Unfortunately, most mining industry joint venture legal agreements provide very few rights or protections for non-controlling partners on human rights and community engagement matters. We recently benchmarked 62 mining legal contracts – including both joint venture agreements and concession agreements with host governments. We found that only 29% of the joint venture agreements included any provisions that explicitly referenced either human rights or community engagement. And even when these agreements included such critical topics, they often included language on only a small subset of 10 potential provisions, and often not very well.

If mining companies are serious about human rights and their commitment to ESG and social license to operate, they need to do better due diligence before entering joint ventures, negotiate legal agreements with stronger protections on human rights and community engagement issues, and implement enhanced governance practices and capacity building to manage their joint ventures responsibly.

For instance, new legal agreements also need to define what human rights standards the joint venture will adhere to – ideally international standards such as the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights or others that establish even more specific and auditable performance expectations. They should also provide the right for companies to directly audit human rights performance and conduct regular human rights assessments (e.g., every two years or as part of any major new investment) and establish the expectation for regular and specific reporting on human rights performance and risks.[1]For a deeper discussion on human rights provisions in the joint venture agreements, see “Time to Stand Up: Elevating Human Rights in Joint Venture Agreements,” Neetin Gulati, James Bamford, Tracy … Continue reading)

Similarly, mining companies will need to raise their game on governance. Our benchmarking of the governance practices of 110 large joint ventures shows that mining joint ventures have substantial gaps and is significantly trailing many other sectors, including oil and gas, chemicals, and industrials. As one specific example, only 6% of all directors on mining industry JVs are women. To be fair, a number of companies, including BHP and Alcoa, are bringing rigor to the governance of their joint ventures. But it is early, early days for the industry as a whole.

Regulators and investors also have a role to play – starting with pushing for improved public disclosure on social factors in non-controlled JVs. Investigative reporting recently showed mining company fatalities are far higher than disclosed by companies when their non-operated JVs are taken into account – and this gulf likely extends to all other human rights and social performance metrics.

Improving public company sustainability reporting standards by covering joint ventures and non-operated assets will be a big step towards giving investors and customers the full picture of the impact of mining activities, and who bears the true cost. It also is an action companies should recognize as an imperative step in our collective march toward a better world.

~ ~ ~

Comments