February Partnership Conversation – Financial Modelling for Joint Ventures

A conversation with Caitlin Johnson.

JV CEOs have one of the toughest jobs in business, and a strong start is critical to success. We examined more than 100 JV CEO transitions to find out how to make them more effective.

JULY 2011 — Being a JV CEO may be one of the most demanding jobs in business. But when transitions are done well – that is, when the shareholders pick the right person, clearly define boundaries, freedoms, and expectations, and the CEO takes the right tone and actions from the start – magic can happen.

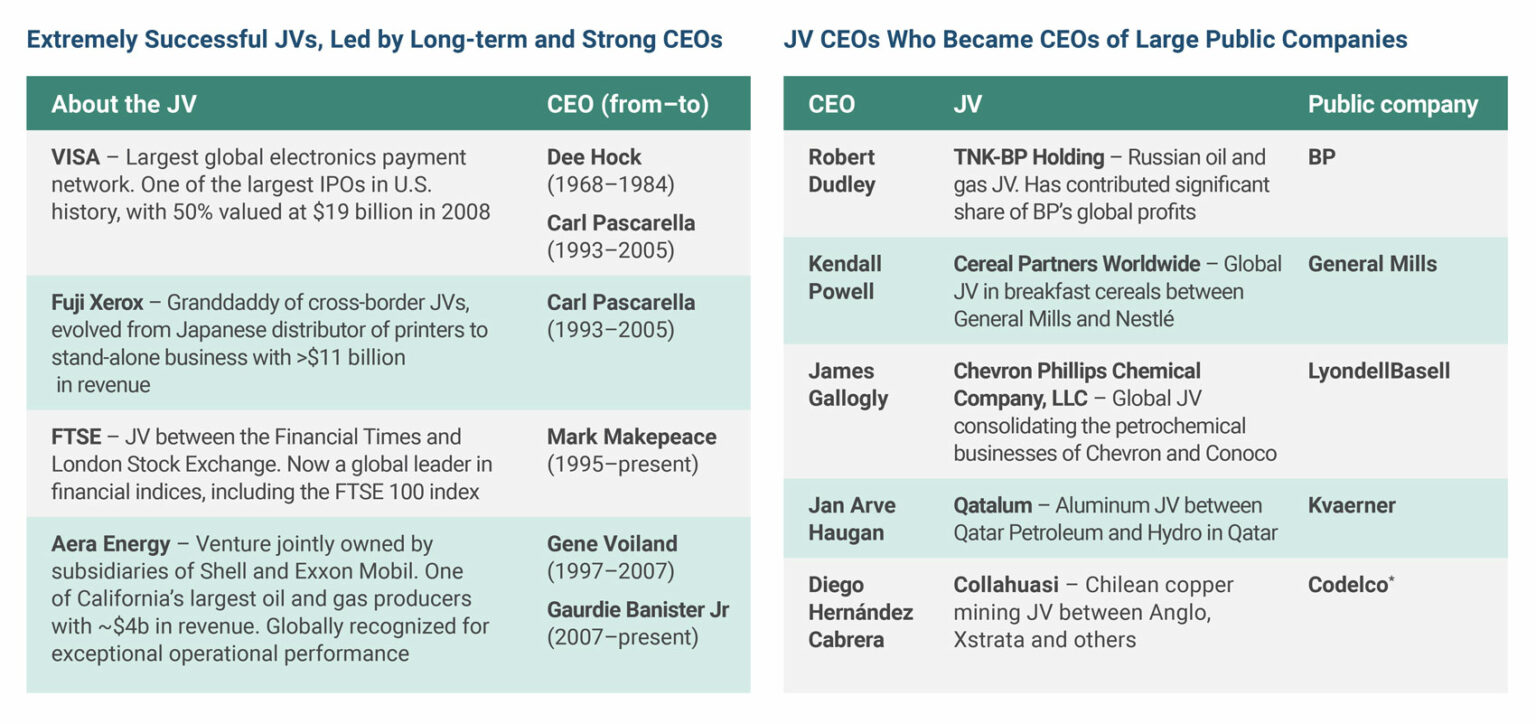

In some instances, the JV CEO stays for years and builds a business of extraordinary value to the shareholders. Think VISA, Fuji Xerox, FTSE, and Aera Energy (Exhibit 1). In other cases, the skills selected for and honed in running a joint venture translate into even bigger roles, catapulting JV CEOs into the executive suite of large public companies, including the JV’s shareholders. Today, BP, General Mills, LyondellBasell, Kvaerner, and Codelco each have CEOs who were recently at the helm of a joint venture.

But it rarely turns out this way.

"*" indicates required fields

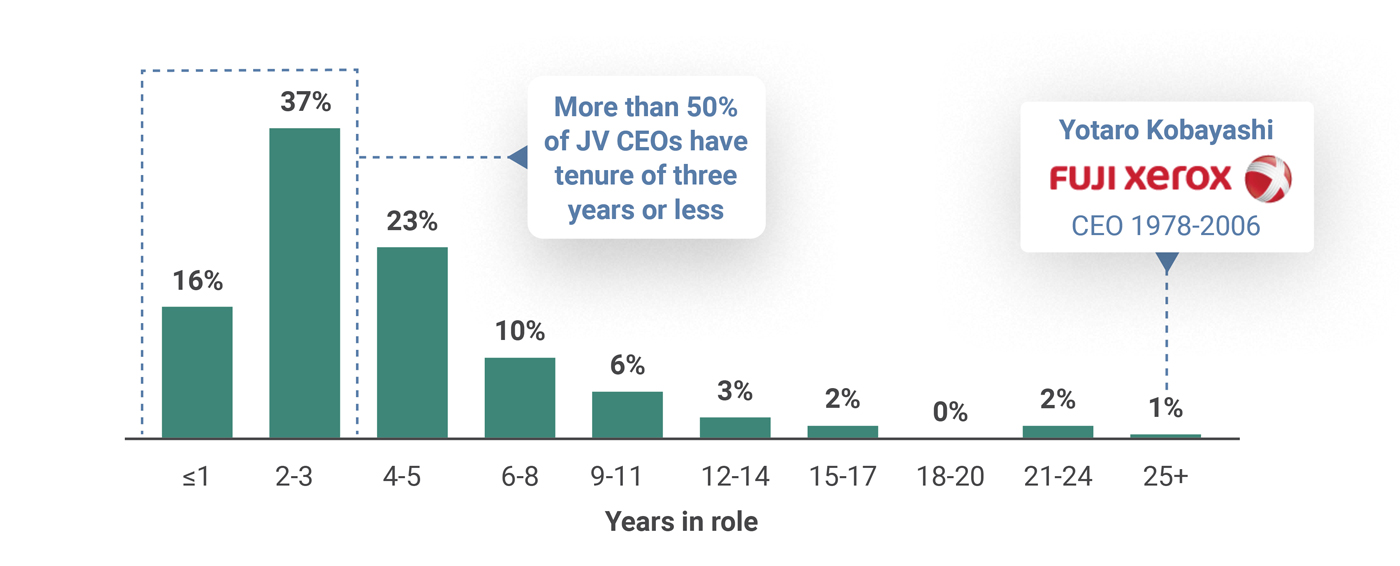

More often, JV CEOs are not well selected, and those picked miss a onetime opportunity to define the role and set a path for success.[1]We use the term “JV CEO” to refer broadly to the position of running a joint venture. Depending on geography and scope of the role, this position may have the title of CEO, Managing Director, … Continue reading As one new JV CEO told us: “The last five CEOs were carried out in stretchers, and most were just dumped on the side of the street.” The median tenure of a JV CEO is less than three years (Exhibit 2) – less than half that of an independent company CEO.[2]Independent company CEO tenure data based on the average S&P CEO from 2000 – 2004. See, “CEO Tenure, Performance, and Turnover in S&P 500 Companies,” John C. Coates IV and Reinier … Continue reading

Why is it that so many good managers struggle as JV CEOs?

* Chilean state-owned company and largest copper producer in the world

Source: Public filings and press releases; Ankura analysis

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

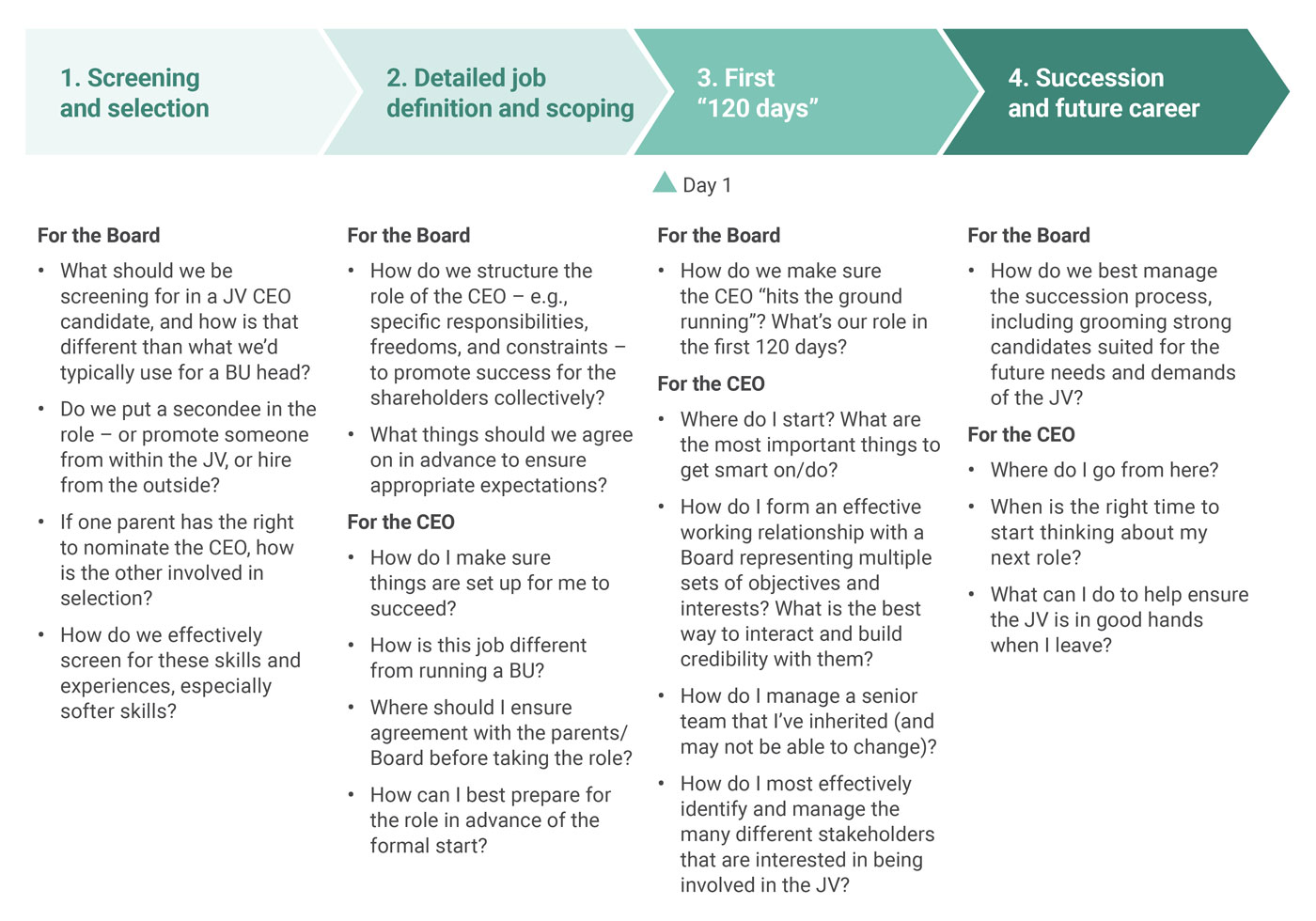

How should JV Boards and parent companies expand the way they search for JV CEO candidates? How can attractive candidates use their leverage prior to accepting the job to define the nature of the role in a way that allows them to succeed? What should new JV CEOs do to maximize impact during their initial period in the role? And how should JV CEOs and Boards approach succession, and manage the exiting CEO’s path out of the JV?

Source: Interviews; Literature search; Ankura analysis

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

To answer these questions, we recently examined more than 100 JV CEO transitions and conducted interviews with several dozen current and former JV CEOs, JV Board members, and HR executives (see “About the Research,” page 8). We focused on the challenges inherent to four key points in the JV CEO transition process: (1) screening and selection; (2) job definition and scoping; (3) the first 120 days; and

(4) succession and future career (Exhibit 3).

The purpose of this memo is to share key findings from this work. It is intended to help parent company executives, JV Board members, JV CEOs, and others with a vested interest in making JV CEO transitions more effective. This work is part of a broader set of findings and tools that we believe is currently missing from many transition processes (see “Related Resources,” page 11).

Source: Ankura

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

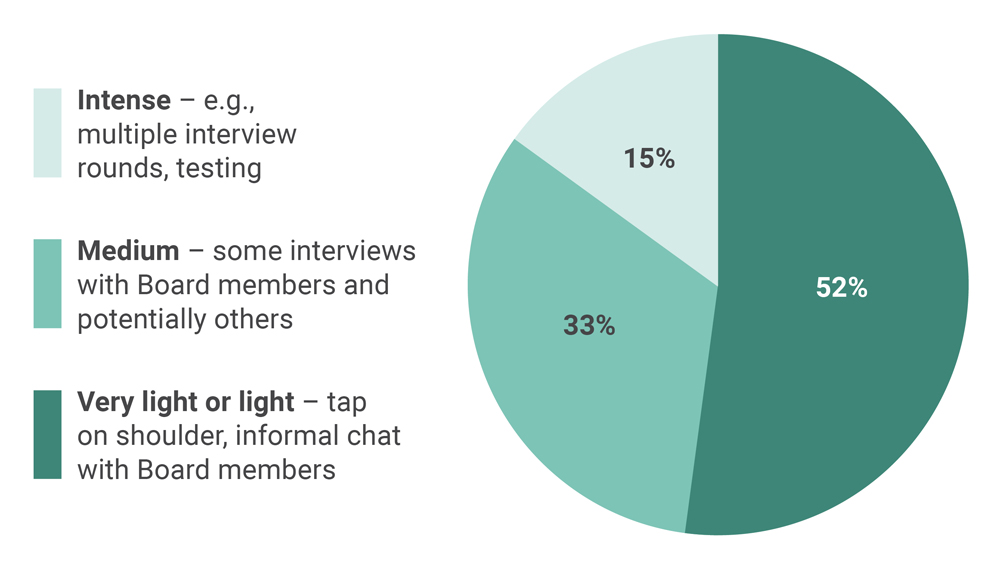

More than 50% of JV CEOs are selected based on a light screening process – i.e., one or two informal conversations or a simple shoulder-tap. In only 15% of cases do the JV Board or parent companies seriously look at multiple candidates, conduct several rounds of interviews, and use any screening techniques, such as psychometric testing, that go beyond interviewing (Exhibit 4).

Source: Ankura

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

This is surprising, given the importance and demands of the job. After all, a JV CEO must perform all the tasks of a Business Unit President but with a deep overlay of added complexity and challenges. Strategy must be forged in a way that not only maximizes market opportunities, but also manages the competing interests and strategic constraints of the individual shareholders. Governance is not just about reporting to a boss and occasionally updating the corporate leadership team on the business’s status; it is about managing a Board, committees, and multiple parent company strategy and planning processes. And building an effective organization often contends with issues like blending disparate cultures and styles, whilst managing a talent pool comprised of venture employees and parent secondees.

Given such challenges, the screening and selection process for potential JV CEOs needs to look for different things than the search for a Business Unit President, and be a more rigorous process than what is currently in place in most JVs.

To be fair, there may be some reasons why JVs tend to be “light” on CEO screening. For instance, our analysis shows that some 70% of JV CEOs are secondees – i.e., executives from one of the parent organizations placed into the JV, typically for 3-5 years. It might be reasonable to conclude that in such situations there is already high familiarity with the candidates and a strong sense of their strengths, skills, and experiences, and therefore a “light” process is sufficient. Interestingly, however, our discussions with JV Board members and HR executives suggest that this inside knowledge is not fully appreciated. In some cases, information about the candidate isn’t systematically captured across that individual’s tenure with the organization. In other cases, softer dimensions of the individual’s performance haven’t been captured, or the information isn’t centrally and easily available to the Board or search committee.

The implication: Boards, search committees, or parent companies should adopt a much more disciplined (and, yes, process-heavy) approach to JV CEO search and selection. Specifically, they may wish to consider some non-traditional approaches to assess the softer skills that are so important to succeeding as a JV CEO. As one Board member described it to us, the job of a JV CEO is a blend of general manager, entrepreneur, diplomat, and international peace negotiator. Strong management and operational skills are important, but softer skills tip the balance between success and failure. These skills are even more important in cross-border JVs where the parent companies are in different countries (which is increasingly the case) and therefore the need to appreciate different cultures and organizational dynamics, and the need to know how to effectively function in that environment, are critical.

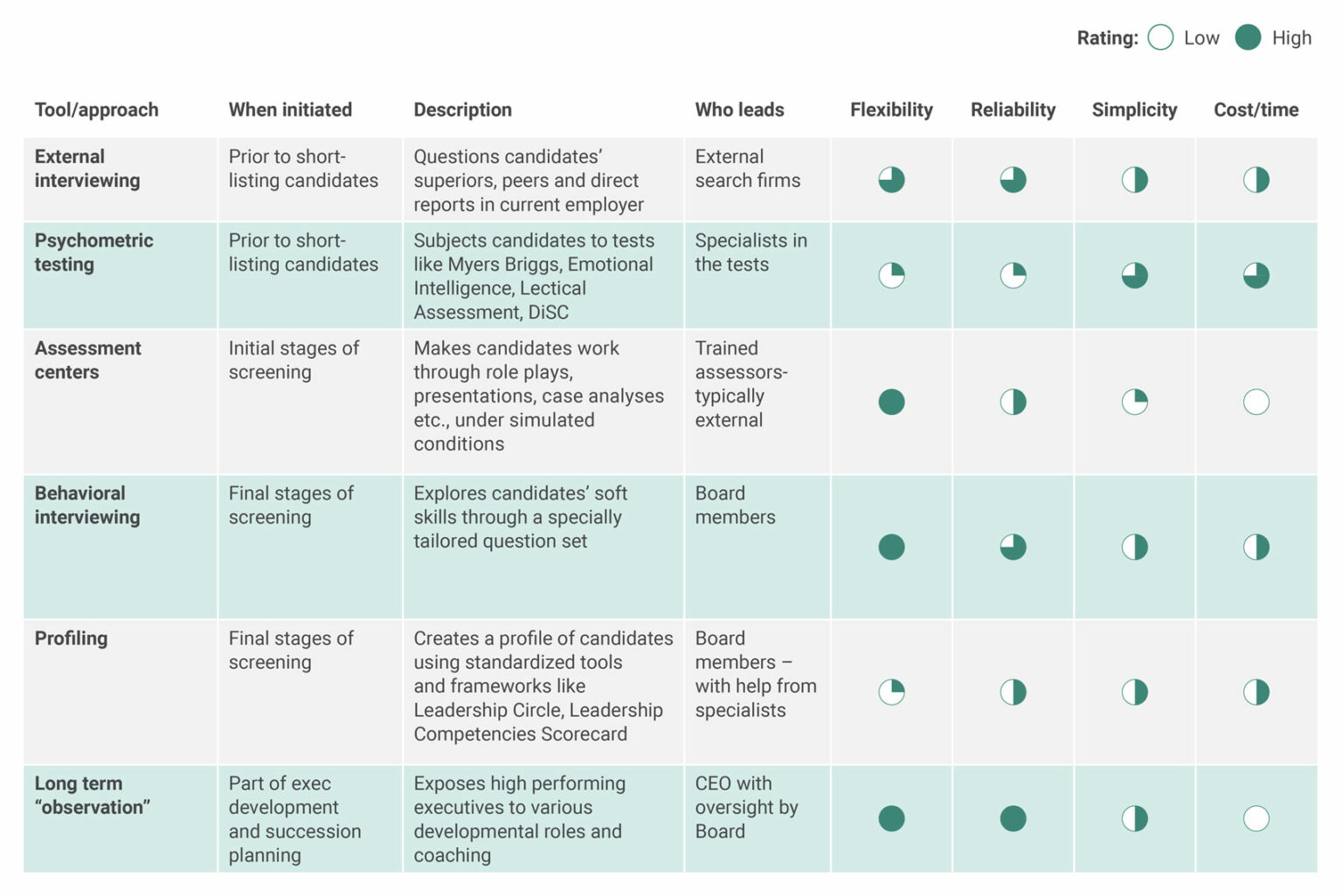

We’ve found it helpful to screen for five types of softer skills (Exhibit 5). Screening for these skills is not easy, as they cannot be seen on a resume or through an ordinary interview. But there are ways to test for them, including alternative interviewing approaches (e.g., behavioral interviewing), psychometric testing, assessment centers that take candidates through a series of exercises, and profiling (Exhibit 6).

Source: Ankura

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

For most incoming JV CEOs, there is surprisingly little clarity on what the shareholders do – and do not – want from the role. Only 50% of CEOs we spoke with saw a basic job description before taking on the role, and rarely did that job description incorporate the unique challenges and constraints of a JV. Even fewer incoming JV CEOs had an explicit conversation and agreement with the shareholders on performance goals or objectives prior to starting the job.

There are different views on how far and hard JV CEO candidates should push for detailed definition. Some view lack of definition and clarity as a negative – an open invitation for misunderstanding and misalignment down the road. And, having seen countless situations where the CEO and the Board later discover they weren’t signing up for the same thing, we agree with them.[3]For example in a large upstream oil JV, the incoming CEO was shocked to discover four months into the job that he did not have responsibility for – or the formal right to provide input into – the … Continue reading

Others counsel caution. Some executives argue that, especially when entering an underperforming JV, an incoming CEO would be wise to wait for deeper definition. They argue that the first task of a new CEO is to figure out what’s wrong, what can and needs to be fixed, and only then define the metrics against which the JV and the CEO should be measured. And, they say, a CEO candidate is unlikely to have sufficient knowledge of the JV to make these determinations before coming in.

We also understand this point of view.

But the problem is that if these things aren’t defined in advance, misunderstanding can fester into outright disagreement that is hard to reverse. We’ve found that sought-after JV CEO candidates enjoy a unique “moment of leverage” between when they are offered the job and before they accept it – one of the few times when it is relatively easy to align the shareholders around the roles of the Board and Management, and the expectations for the business. CEO candidates should not squander it.

What then should the CEO candidate (and Board) do to better define key assumptions, expectations, and parameters of the job? We’ve found that there are a few issue areas that merit special attention upfront, and that the JV CEO candidate’s “offer package” should go beyond a traditional job description.

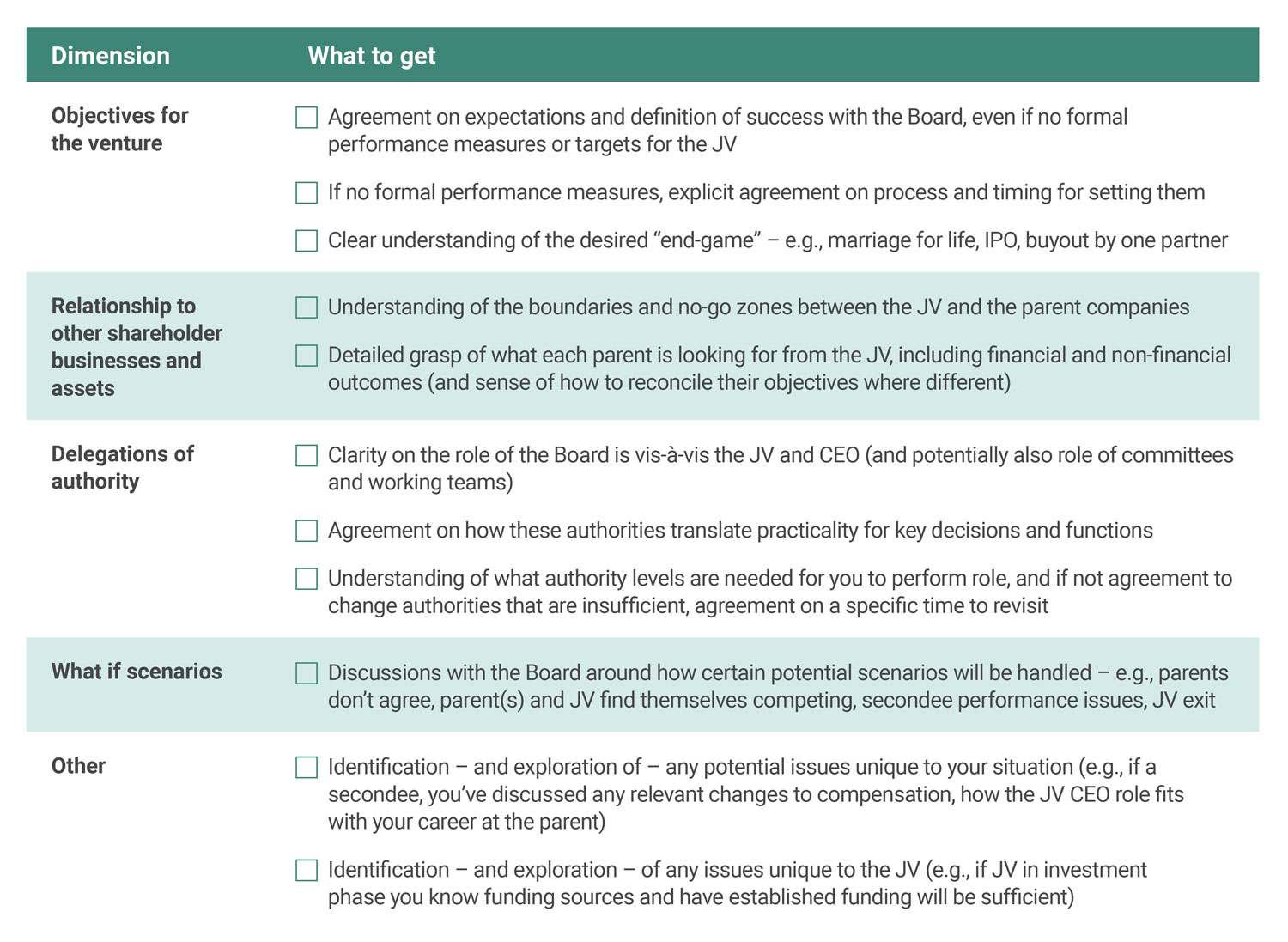

To help Boards and incoming CEOs, we’ve created a checklist for scoping the role (Exhibit 7). The checklist is organized around five areas where agreement is most important and often incomplete in joint ventures: (1) performance objectives, (2) relationship of the JV to other shareholder businesses and assets, (3) delegations of authority and how power is truly shared between the JV Board, CEO, and other influencers, (4) different “what if” scenarios, and (5) other items that are specific to either the circumstances of the candidate or venture.

There are different ways in which such agreement might be expressed. In some cases, it is possible to directly embed this into the JV CEO’s job description or performance contract. But incoming JV CEOs have used other mechanisms as well. For example, in an energy technology JV, the incoming CEO drafted and had Board members from each shareholder sign a three-page description of “what success looks like” in 2011. It was broken down into six areas – health and safety, operations, costs/financial metrics, organization and talent, community, governance/shareholder management. Each of the six areas was weighted, and included pinpoint criteria of success.

Source: Ankura

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

For things that either can’t be clarified in advance or where there is a preference for some mutual discovery, there should be explicit agreement between CEO and Board as to when those things will be revisited and agreed on and a specific date committed to (e.g., 6 or 12 months into the CEO tenure). For example, in a South American industrial sector JV, the CEO’s job acceptance was contingent upon the Board’s commitment to sponsor an independent review of the governance and committees, as well as a peer review of shared services within the first six months of the CEO taking the job.

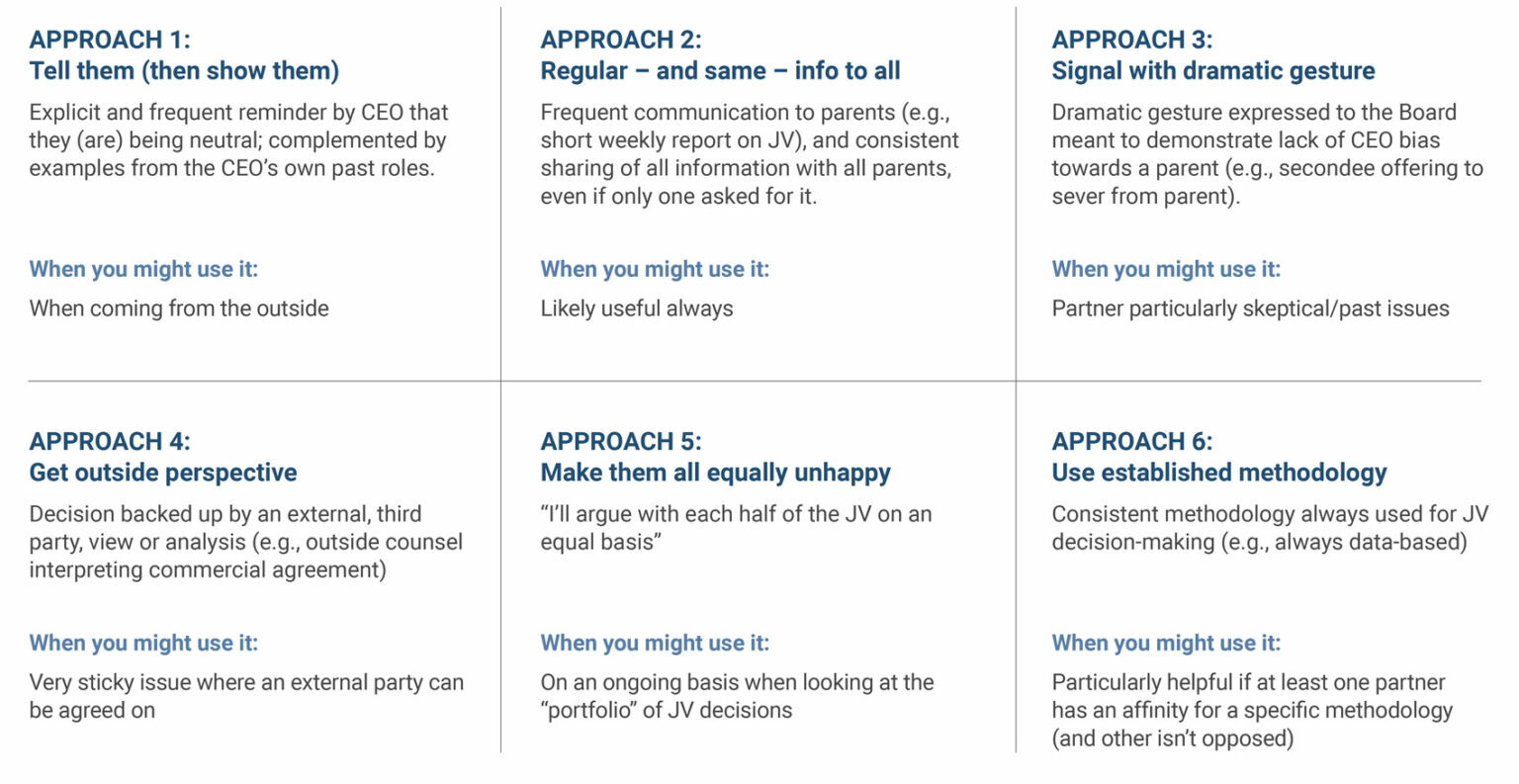

Given that some 70% of JV CEOs are secondees, many incoming leaders are perceived to be partisans, consciously or subconsciously biased toward one shareholder. Unless the CEO is an outside hire, promoted from within, or is part of an unusual dual leadership structure (such as Co-CEOs), a new JV CEO is well-served to take steps to establish neutrality and independence, and do so clearly and early in their tenure.

There are multiple ways to do this (Exhibit 8). One early technique is to allow the other shareholder(s) to actively participate in the JV CEO nomination and interview process even if the CEO position is a designated “slot” to be filled by one shareholder.[4]For further perspectives on selecting and managing secondees, including seconded CEOs, please see “JV Secondee Policies: Cross Company Calibrations,” “Secondee Guidelines,” and other research … Continue reading

Source: Ankura

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

Getting real input from the other shareholder(s) can go a long way to making the Board feel it was their collective choice, rather than an individual foisted upon them. Granted, this is less up to the CEO than to the Search Committee or the parent with the nomination/appointment right. However, CEOs can play a role here by insisting that they are interviewed by all parents of the venture.

Another approach is for the CEO to be very deliberate in communicating equally to all shareholders. For example, the CEO of a large U.S.-Japanese automotive JV copied each of his Lead Directors on all emails to the others (including answers to questions asked by an individual), and tried hard to avoid one-on-one meetings with Board members from the shareholder who appointed him. Other CEOs have adopted a regular (typically monthly) cadence of communication to all Board members. This allows filling everyone in on what’s happening with the JV in a consistent fashion, and enables the CEO to reduce one-off questions or meetings involving just one parent.

In another example, the incoming CEO of a large natural resources JV has chosen to no longer participate in the weekly regional leadership meetings of his appointing shareholder. While this creates some risk of becoming disconnected from his company, it is more than outweighed by the benefits of being seen as independent by the national oil company partner and oil minister.[5]Of course there are risks to establishing too much neutrality. For example, the President/General Manager of Sable Offshore Energy, joint venture in eastern Canada, wound up in a public dispute and … Continue reading

In some cases, we’ve seen JV CEOs who made a dramatic gesture to solidify their independence. One seconded JV CEO offered to resign from the parent company and fully tie his career to the JV. In another case, the seconded CEO insisted that the Board – not his parent company sponsor – lead his review and base his fixed pay and short-term incentive compensation entirely on performance against the Board-defined scorecard (something that was highly unusual for seconded staff into JVs). Both of these offered strong signals to all shareholders that the CEO is not biased towards an individual parent.

Any of these can work, and it is up to each CEO to determine which approach fits best with his or her own personality, preferences, and circumstances. For example, if the preceding JV CEO was viewed as biased, the incoming CEO may want to use multiple approaches for establishing that things have changed. And, in fact, in our experience, effective CEOs do tend to use a combination of approaches – rather than just one – to establish themselves as a fair or neutral leader of the JV.

Succession is a high-risk time for all companies. Given the stakes and the scrutiny by analysts and investors, most public companies in the U.S. and Europe have at least invested time in developing a succession plan for the CEO and in developing a bench of talent that can be drawn upon to fill vacancies in the top 10 – 20 positions.

Not so for JVs, where some structural challenges impede succession planning. First, the JV Board – which should own the process – often doesn’t fully embrace or appreciate its responsibilities. To complicate matters further, JV Boards tend to turn over with high frequency – in fact, they experience three times the turnover of a corporate Board.[6]Median JV Board Director tenure is 30 months, compared to more than nine years for corporate directors of U.S. public companies. (Source: Ankura, 2009 research on JV Boards, and Directors & … Continue reading This makes it hard to maintain consistent ownership over a process that is inherently long-term. Finally, almost 60% of JVs do not have an HR/Compensation Committee, so the group on the Board that is most likely to focus on succession doesn’t exist.

One potential consequence is that less than 20% of JV CEOs come from inside the business[7]For further details on sourcing of JV CEOs, Joint Venture Advisory Group subscribers please see, “JV CEO Transitions,” July 2011, available within the subscriber access section of our … Continue reading – an indication that JV Boards may be insufficiently focused on long-term succession planning and building a strong top team within the venture.

A well-functioning succession process needs to be managed on two parallel paths. First, the succession process should identify potential candidates to be the next JV CEO, linking into the CEO selection process. This is not intellectually complicated, but it is about having a formal process to discuss the evolving needs of the JV, the skills required to lead it in the future, and a list of potential successors that match the anticipated needs of the JV in the future. For example, in one manufacturing JV, the Board meets twice a year to discuss with the CEO the performance of the senior people on the JV management team. At the same time, they also discuss succession for these key roles. Then the CEO leaves the room, and the Board has the same conversation about him.

Or consider a large natural resource JV where one shareholder has the right to appoint the JV CEO. Here, the Lead Director is responsible for identifying the need for a new JV CEO 12-24 months in advance of the current CEO’s departure. If there is no strong candidate within the JV or parent company, the Lead Director will look for an external hire. And that is exactly what happened recently. To help manage the transition process and acclimate the future JV CEO to the parent company, the Lead Director brought the candidate in to work in the parent company for a year before transitioning into the JV.

The second path of a well-oiled succession involves managing the outgoing CEO. When the CEO is a secondee, his or her parent company needs to think about re-entry. This is important not only to the future of that individual and the parent’s ability to leverage their skills, but it also has an indirect impact on the ability to get top talent into a JV in the future. There is nothing that causes talented executives to question whether or not they should take a job in a JV more than seeing previous CEOs come back into lesser jobs in the parent company, or not come back at all.

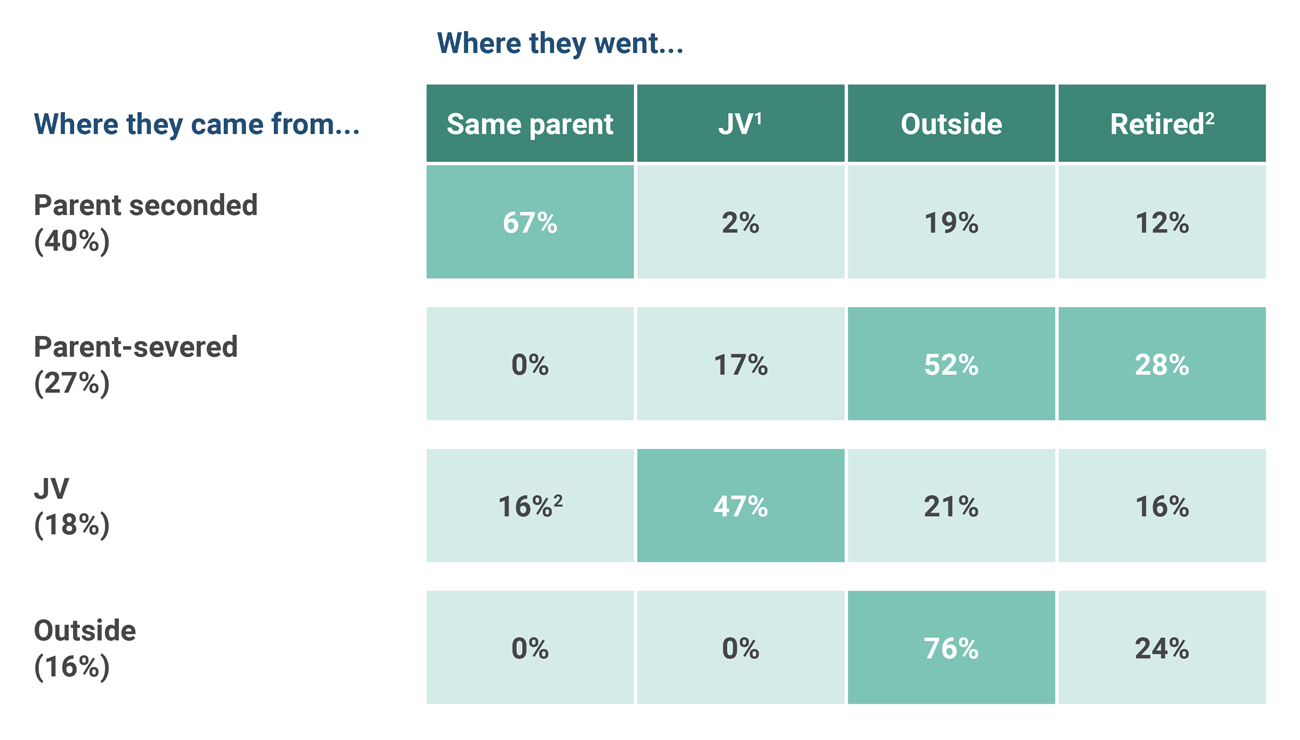

We took an in-depth look at where JV CEOs tend to go when their tenure with the JV is up. Based on an analysis of 108 CEOs, we found that they largely go back where they came from. For example, 67% of seconded CEOs went back to the same parent, and 76% of CEOs hired from outside the JV and parent companies go back outside (Exhibit 9).

1 Moved into a lower position in the JV (e.g., COO or other Executive Officer).

NOTE: this is a small number – 3 in total in our data set

2 Includes fully retiring, shifting into working retirement (including Board role or advisory/consulting), and looking for other full-time employment (typically associated with a forced step-down)

Source: Press releases and other public filings; Ankura

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

A higher number – 14% – of JV CEOs became CEOs of wholly-owned companies immediately following their stint as JV CEO, including two who became the CEO of one of the venture’s parent companies. A much larger portion, however, treaded water or fell into roles that were perceived to be smaller relative to the JV CEO position.

A key force at work: mismatched perceptions. When an executive emerges from a tour as a JV CEO, they will often (and rightfully) see the experience they’ve had running a company, owning the strategy, and managing a Board with complex dynamics as a big and demanding job.[8]See, “Memo to a New JV CEO: What does it take to succeed at the toughest job in business?” The Joint Venture Exchange, December 2008. But parent companies often see it differently. They look at returning JV CEOs as a slightly lesser version of a business unit head – someone who was not quite good enough to run a 100%-owned business unit. The net result: misalignment on the potential and next role for the returning JV CEO.

What is to be done? When an outgoing CEO is a secondee, the parent company needs to not only actively manage the individual’s future career development and path while they are in the JV, but also recalibrate how the skills and experiences proven in the JV translate into appropriate performance ratings and career potential. Likewise, the JV CEO needs to ensure they are maintaining ties into the parent organization, keeping up to date on changes happening with the parent, and proactively broaching the conversation early on their next role.

Not all outgoing JV CEOs are secondees or want to return to the parent, of course. Within this group, we’re seeing an increasing number of outgoing CEOs, including those at Eurostar, Sematech, and GE-Hitachi Nuclear, stepping up into the role of non-executive chair of the JV. In many cases, the chair’s focus is on governance – providing comfort to the shareholders, and helping the new CEO forge alignment among the Board, whose interests, pressures, and influences may not be immediately obvious to a new CEO. Done well, it can be an extraordinarily helpful construct during JV CEO transitions, and beyond.

~ ~ ~

JV CEO transitions present a challenge and an opportunity. As one Board member reflected: “The difference between having the wrong person in there and having the right person there, was roughly the difference between a 4-5% return and a 12-15% return.” After all, isn’t that what this is all about?

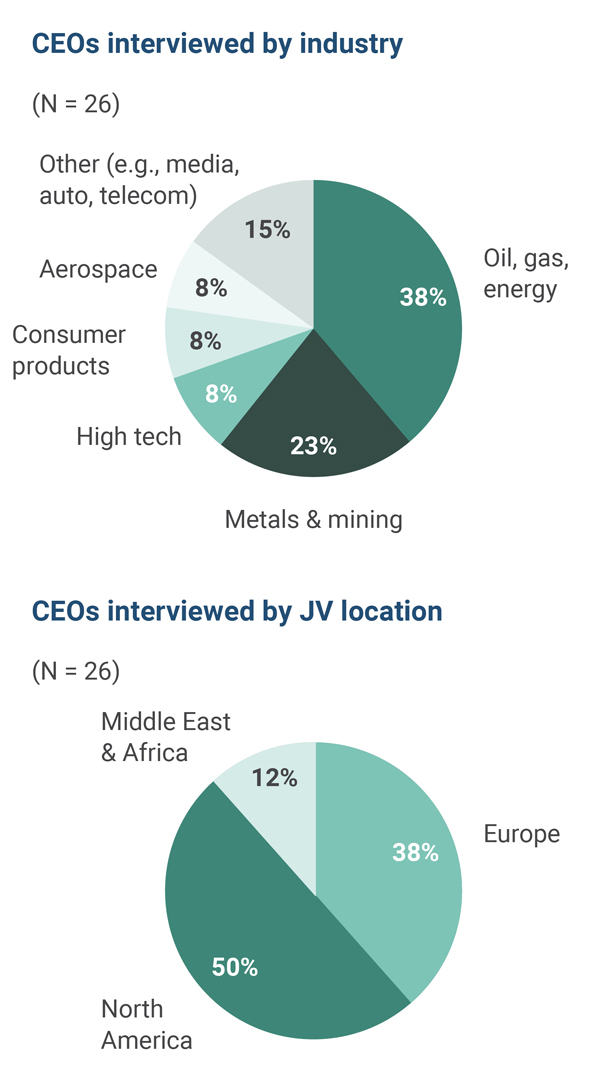

In the spring of 2011, the Joint Venture Advisory Group conducted an analysis of JV CEO transitions and what makes them effective.

As part of this work, we interviewed 26 CEOs or individuals in equivalent roles, talked to JV Board members and HR professionals, looked at other external research on JV CEO transitions (outside of JVs), and performed an outside-in analysis on JV CEO transitions using publicly available information. We also tapped into previous analysis we had done benchmarking CEO effectiveness and examining delegations of authority inside JVs.

Taken together, these inputs allowed us to understand what JV CEOs, and those involved in JV CEO transitions in the parent companies need to do to maximize the effectiveness of JV CEO transitions. Our findings were further informed by our own extensive direct client experience with joint ventures.

Source: Ankura

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved

Download the PDF version of this article.

We understand that succeeding in joint ventures and partnerships requires a blend of hard facts and analysis, with an ability to align partners around a common vision and practical solutions that reflect their different interests and constraints. Our team is composed of strategy consultants, transaction attorneys, and investment bankers with significant experience on joint ventures and partnerships – reflecting the unique skillset required to design and evolve these ventures. We also bring an unrivaled database of deal terms and governance practices in joint ventures and partnerships, as well as proprietary standards, which allow us to benchmark transaction structures and existing ventures, and thus better identify and build alignment around gaps and potential solutions. Contact us to learn more about how we can help you.