Part two in a two-part series

February 2020 — GIVEN THE POTENTIAL risk exposure from joint ventures and the increasing pressure on non-operators to get a grip on it from key stakeholders, it’s not surprising that the typical JV operator can feel buffeted by an avalanche of intrusive and overlapping partner assurance efforts. And while we applaud non-operators waking up to their risk exposure, we also echo the Institute of Internal Auditors’ challenge for risk management professionals:

It’s not enough that the various risk and control functions exist – the challenge is to assign specific roles and to coordinate effectively and efficiently among these groups so that there are neither “gaps” in controls nor unnecessary duplications of coverage.[1]See “The Three Lines of Defense in Effective Risk Management and Control,” The Institute of Internal Auditors, January 2013

In Part 1, we explored the current state of play in joint venture risk management and made the case that non-operators and operators alike need to coordinate their individual lines of defense and develop a joint risk management framework tuned to the unique circumstances of their JV.

The purpose of this article is to discuss a broader set of opportunities for companies to elevate their risk management game in joint ventures. Specifically, based on our recent client work and comments from participants in our joint venture roundtables in the upstream oil and gas, downstream and chemicals, and mining sectors, we see opportunities for companies to close gaps in risk-related operator screening and due diligence, in contract drafting for risk management terms, and in expectations internally – and externally – for ongoing governance of risk. Closing these gaps will better position non-operators and operators as they develop effective and efficient joint risk management frameworks with their partners.

Elevating the Risk Management Game

1) Operator Screening and Due Diligence. Financial institutions have long been required by regulators to engage in “know your customer” diligence before taking on a new client – a process that entails verifying the potential client’s identity and evaluating the potential risk exposure from that client (i.e., the probability of the client engaging in illegal conduct). So too should JV non-operators strive to “know your operator” before signing a JOA or JVA – that is, understand the culture (identity) of the operator and the potential risk exposure from the operator (i.e., the probability of the operator failing to properly manage operational, financial, HSE, or other matters). As we’ve written elsewhere, due diligence is the first and best opportunity to understand whether a potential operating partner has a risk management philosophy that is fit-for-purpose in the JV and aligned with the company’s own risk management philosophy.[2]See James Bamford and Piers Fennell, “Giving JV Diligence its Due,” The Joint Venture Deal Exchange, April 2015.

When a company is considering forming or farming into a joint venture as a non-operating partner, its required due diligence should always include an independent baseline assessment of the venture’s risks, with a focus on high-impact HSE risks related to process safety, asset integrity, and environmental risks. But the due diligence should also include an assessment of the Operator’s HSE and risk management policies, systems, and capabilities, as well as its financial controls and business ethics policies, and include a gap analysis to those of the company (Exhibit 1).

Ideally, this due diligence would confirm that the Operator’s risk management systems and capabilities are at least as good as those of the company in practice, even if the specific details vary. And to the extent that the Operator is found to have a risk management approach less mature than that of the non-Operator, the company must take a purposeful decision to proceed, based on its own risk appetite and a reasonable view of its ability to move the Operator up the maturity curve over time. No amount of influencing will turn a wildcat independent driller into a mature risk management organization overnight (though perhaps it might over a decade).

Of course, any decision to proceed if the Operator has a less mature risk approach can and should come with certain caveats – namely, the additional JV contractual terms related to risk management rights and protections that the company ought to seek before putting its signature on the legal agreement.

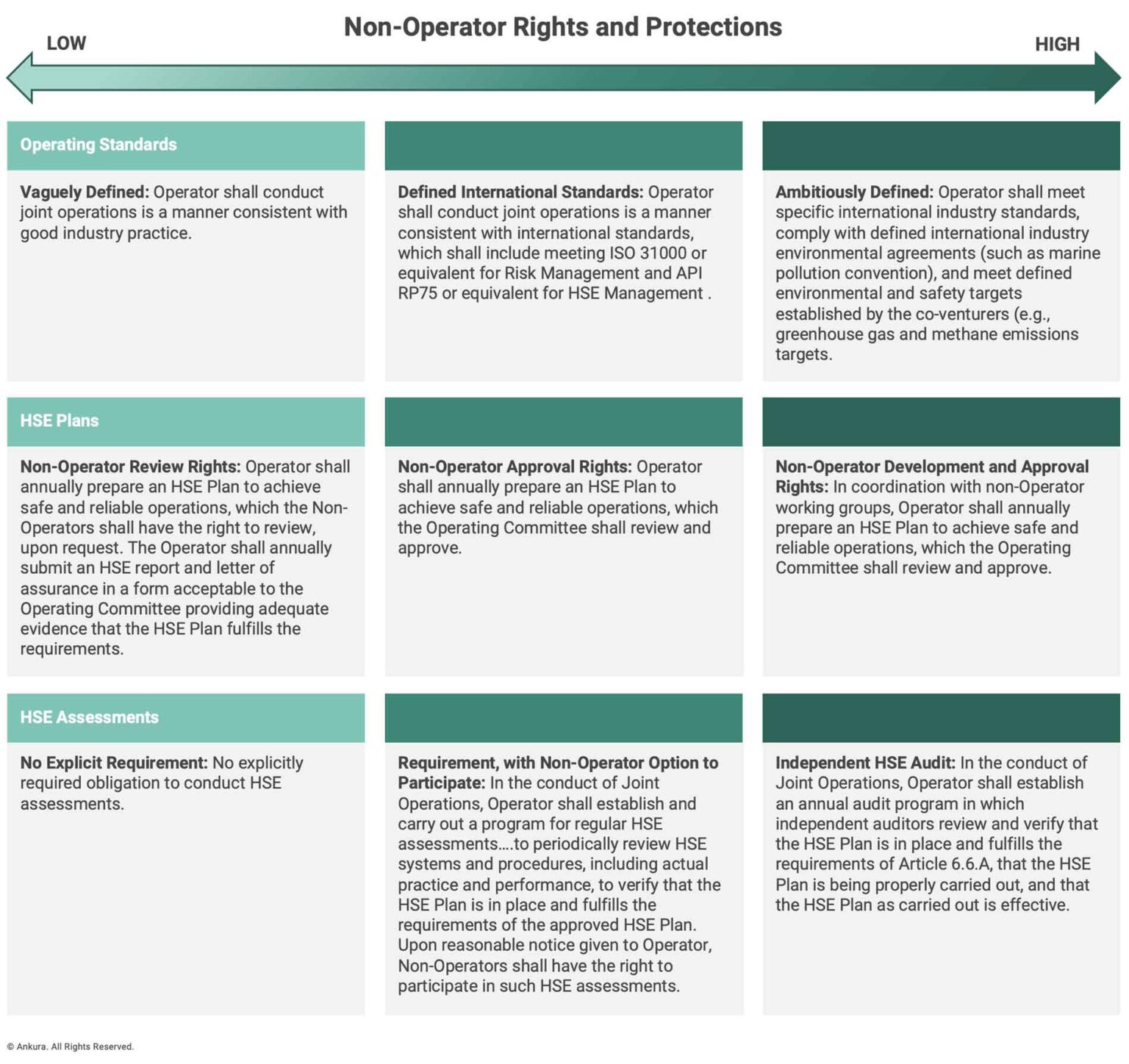

2) JV Contractual Terms. Depending on due diligence findings and its negotiating leverage, a non-operating partner may have the desire and the opportunity to negotiate contractual terms that provide additional rights and protections on HSE risk management and reduce HSE risks overall. Natural resource companies seeking to raise their risk management game in non-operated JVs might consider expansive answers to a set of questions across key deal terms related to risk (Exhibit 2). For example, non-operators might want to make clear that in addition to receiving the ongoing operational and performance data described in the typical industry model form agreement, they also want access to a broad swath of HSE risk-related information – like risk registers and controls, and risk mitigation plans filed with regulators.

Our review of industry model-form joint operating agreements and various legal agreements suggests that most non-operators have not yet invested in a holistic approach to risk management deal requirements – and as a result, have the chance to take a more aggressive posture on almost all contractual provisions relevant to HSE risk management, including those pertaining to Operating Standards, HSE Plans, HSE Assessments, Information and Reporting, Audits and Assurance, and Operator Removal. To illustrate the difference between “typical” and “strong” practice, consider terms pertaining to Operating Standards, HSE Plans, and HSE Assessments (Exhibit 3).

For example, on Operating Standards, typical industry contractual terms feature vaguely-defined calls for the Operator to conduct joint operations consistent with “good industry practice”, without defining what good industry practice is, whether that industry practice is defined at a domestic or international level, and how it relates to domestic laws.

In contrast, strong contractual language would define what international standard(s) the Operator would operate the assets in a manner consistent with (e.g., those established by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) or American Petroleum Institute (API)), as well as whether the Operator is expected to comply with international environmental conventions and treaties or meet defined environmental and safety targets established by the co-venturers.

Or consider HSE Assessments, where typical agreements are silent on the concept of having any formal review of the Operator’s HSE risk management systems and procedures, even if only a self-assessment by the Operator. At least some model forms in recent years have moved towards requiring that the Operator periodically review and report on its HSE systems, though strong contractual language would shift towards requiring an independent audit that the Operator’s HSE approach is defined, carried out as defined, and effective.

Stepping back, companies should create major clauses guidance that includes strong contractual terms on HSE and risk management as a non-operator, seek to negotiate these terms into venture agreements, and report where they have and have not succeeded in negotiating these terms.[3]For additional details, please see James Bamford and Tracy Branding, “No Clause for Concern: Developing a Major Clauses Guide for JV Agreements,” The Joint Venture Exchange, April 2019.

3) Ongoing Governance. We have long advocated for, and written extensively about, the importance of standards for ongoing governance of JVs, which many companies are now moving to adopt – for example, setting single-point internal accountability for the performance and risks of each JV, defining the role and expectations for company JV Directors, and requiring the use of influencing plans.[4]See James Bamford et al, “Joint Venture Governance Index: Calibrating the Strength of Governance in Joint Ventures,” Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance, March 2020.

Similarly, we’ve advocated for joint venture partners to collectively adhere to standards of excellence for how the governance system itself functions (i.e., the activities and relationships between the Board, Committees, Management, and partners). Our research shows that JVs with good governance are strongly correlated with good performance. And we believe that companies pursuing excellence in HSE risk management should separately define a set of standards related to risk management across the lifecycle of the JV (Exhibit 4).

These standards would cover (1) how the company’s asset teams would internally approach HSE risk management, and (2) company expectations for how a JV governance system and Board should approach HSE risk management – ideally influencing how the JOA is written as well as ongoing governance practices and serving as a clear “end state” for the company’s asset teams to pursue by influencing the operator.[5]We recognize that any standards related to the Board and governance system are aspirational to the extent that they cover expectations not in the JOA – acting instead as a roadmap of outcomes the … Continue reading

Many companies have adopted one or two of the sample standards described in Exhibit 4, but few (if any) have adopted a broadly holistic approach to risk management. For example, only 11% of oil and gas JVs in our database currently have a Risk Committee, suggesting broad room for adoption. Or consider the question of joint audits, where the Dow Corporation was an early mover in setting expectations for the use of joint audits and developed a set of joint audit protocols for use in all its JVs – but few have followed the same path.[6]See James Bamford, “Are Your JVs a Ticking Time Bomb?”, The Joint Venture Exchange, June 2009.

Risk exposure is inherent in any business, especially in businesses operating on geographic and technological frontiers. But inherent exposure does not have to mean inevitable occurrence. With countless lives and dollars potentially at stake, what company can afford not to invest in keeping risk at bay in its joint ventures.

Comments