Part one in a two-part series

Joint ventures unmistakably expose non-operating partners to material risk. For evidence, look no further than the losses and precipitous share price declines that non-operating partners Anadarko and Mitsui saw following the Macondo oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, the financial and reputational damage that BHP and Vale experienced from the tailings dam failure at their independently-managed Samarco mining JV in Brazil, or the losses that New Zealand dairy giant Fonterra suffered following deaths caused by contaminated formula manufactured and sold by its partner-controlled Chinese JV. And it’s not always a single dramatic event; many non-operators feel akin to the “frog boiling in the pot” as they realize the totality of their JV exposure from multiple risks accrued slowly over time.

Over the years, we have commented on and analyzed different aspects of managing risk exposure in non-operated and non-controlled joint ventures. We have argued that while companies see joint ventures as a way to shift, share, or otherwise reduce their risk exposure, JVs inherently, and paradoxically, introduce other JV-specific risks due to the partnership structure that needs to be managed. These include partner misalignment and strategic inflexibility, IP leakage, unexpected tax and accounting impacts, and – as Anadarko, Mitsui, BHP, Vale, Fonterra, and others can attest – financial and reputational risk from operator actions.[1]James Bamford, “Joint Venture Risk – and How to Manage It,” The Joint Venture Exchange, February 2013.

To be clear, joint ventures are not inherently riskier. For example, our analysis shows, contrary to the views of some in the natural resource sector, that independently-managed joint ventures do not appear to have a higher prevalence of major HSE incidents compared to ventures operated by experienced partners.[2]Lois D’Costa, “Are Joint Ventures More Prone to Major HSE Incidents?” The Joint Venture Exchange, September 2016. But we do believe that non-operators should be more proactive in identifying their JV risk exposures and engaging with operators to assure those risks are well-managed.

Ours is not the only voice in the chorus.

In the face of high-profile HSE incidents and broader societal pressures, regulators in certain countries – most notably Norway and the UK – have dialed-up expectations of non-operating partners in upstream oil and gas ventures to “see-to-it” that HSE and other risks are being properly managed by the operator.[3]See Norway – Act 29 of November 1996 No. 72 relating to petroleum activities, Section 10-6 subsection 2; UK – [insert citation] More recently, external groups, such as the Environmental Defense Fund, have started to aggressively push for companies to improve the HSE performance and set HSE targets for non-operated assets.[4]Taking Aim: Hitting the Mark on Oil and Gas Methane Targets, Environmental Defense Fund, April 2018

Many international natural resource companies have come around to a similar view, and have adopted some sensible – albeit limited – contractual and policy expectations related to HSE risk management in non-operated joint ventures. For example, the 2012 revision of the AIPN Model International Joint Operating Agreement, in wide use outside North America, introduced new obligations on operators related to creating HSE plans and subjecting them to annual reviews by the non-operator(s). Beyond that, some firms have layered in expectations that the operator formally and clearly assign organizational responsibility and accountability for HSE leadership, that HSE requirements be incorporated into the JV’s overall planning, target-setting, and resourcing process, and that the company as non-operator periodically conduct an independent HSE risk assessment of the operator and its management systems and capabilities.

But these changes aren’t enough. To become excellent in HSE risk management in non-operated joint ventures, companies will need to act on multiple fronts.

Specifically, based on our recent client work and comments from participants in our joint venture roundtables in the upstream oil and gas, downstream and chemicals, and mining sectors, we see opportunities for companies to elevate their games in four areas. Part 1 of this series will focus on reconceptualizing the collective risk framework used in non-operated ventures, while Part 2 will focus on closing gaps in operator due diligence, contract drafting, and ongoing governance.

TAKING RISK FRAMEWORKS TO THE NEXT LEVEL

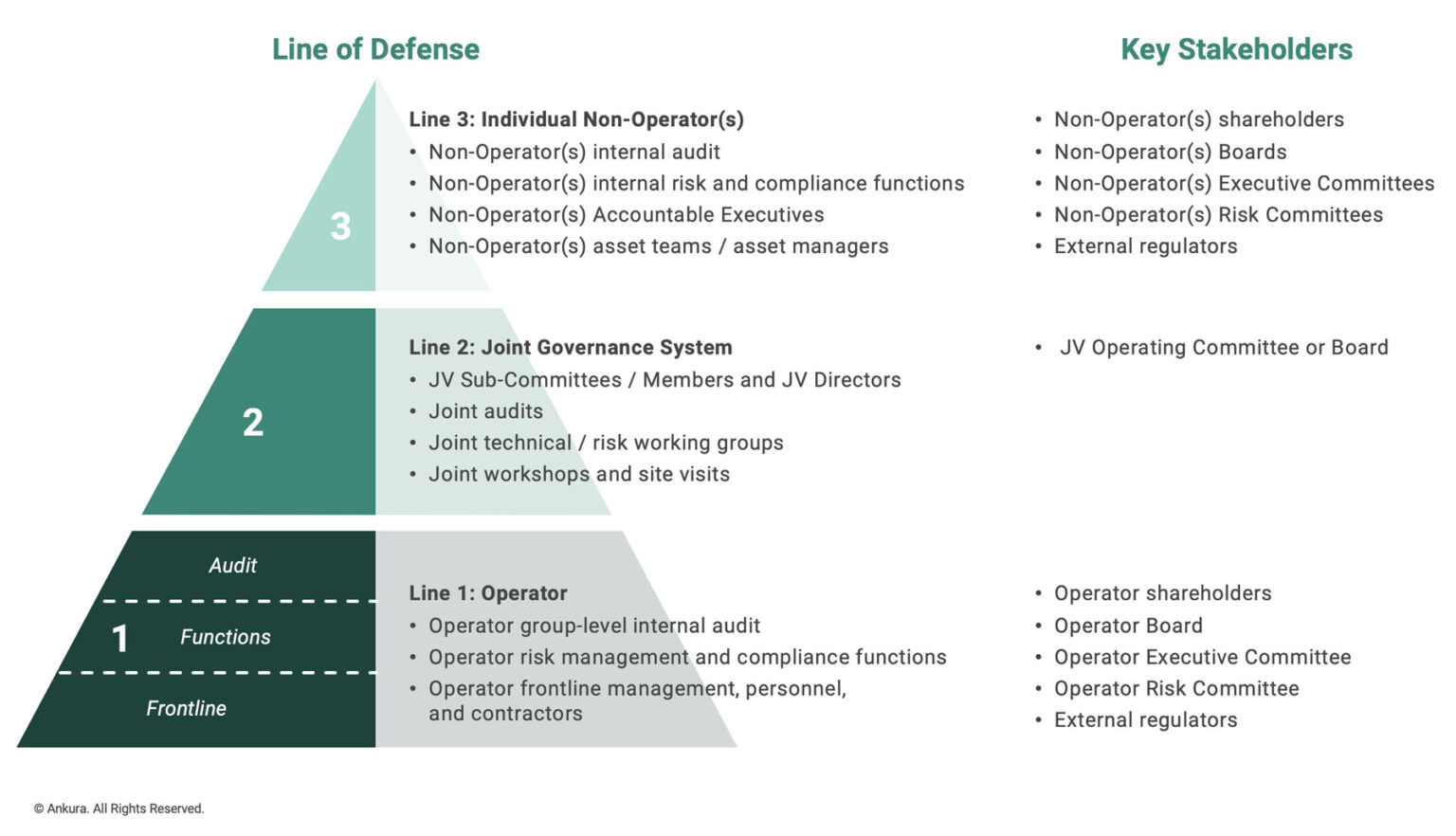

Over the last twenty years, many companies have adopted a set of powerful risk management frameworks and approaches, including corporate risk matrices, risk bow ties, and more recently the Three Lines of Defense risk model. Originally promulgated by the European Union to holistically address risk in financial institutions, the Three Lines of Defense risk model is a way to clarify the essential accountabilities across a diverse team of risk and control professionals, including frontline staff, internal auditors, enterprise risk management specialists, compliance officers, internal control specialists, and fraud investigators. As stated in an Institute of Internal Auditors whitepaper, “It’s not enough that the various risk and control functions exist — the challenge is to assign specific roles and to coordinate effectively and efficiently among these groups so that there are neither gaps in controls nor unnecessary duplications of coverage.”[5]Institute of Internal Auditors, Three Lines of Defense in Effective Risk Management and Control, IIA Position Paper, January 2013.

Under the Three Lines of Defense model, operating management is the first line of defense, ultimately accountable for implementing and using risk management systems day to day. Various risk, control, and compliance oversight functions serve as the second line of defense, with the role of establishing and maintaining internal risk management frameworks, procedures, policies, and supporting operating management in setting risk management goals. Internal audit stands as the third line of defense, with the fundamental role of providing independent assurance to key stakeholders, including senior management and the board.

THREE LINES OF DEFENSE IN A JV CONTEXT

Reality on the Ground. The Three Lines of Defense model is now prominent across large energy, mining, chemical, and other companies. Unfortunately, joint ventures introduce additional actors and complexity that the traditional model does not contemplate.

In simple terms, the reality on the ground in joint ventures is that there are actually five lines of defense. The first three are the classic lines – front line operators, functional risk and compliance staff, and internal audit – which are the purview of the operator. Above these, however, there is a joint venture governance system line of defense, directed by the joint venture board or operating committee and composed of board, committee, and audit team members and other functional experts from the non-operators, supporting the collective governance responsibilities of the non-operators. Above this is a fifth and final line of defense composed of the individual non-operating partners, which as individual owners likely have “check-the-checkers” contractual rights to conduct site visits, request information, or perform unilateral audits.

Oh my.

This creates a paradox: These added lines of defense, which are intended to better manage risks, actually can introduce additional risks if not clearly and tightly coordinated, including non-operating partner overreach, excessive information demands on the operator, muted accountabilities, and weaker risk management performance overall.

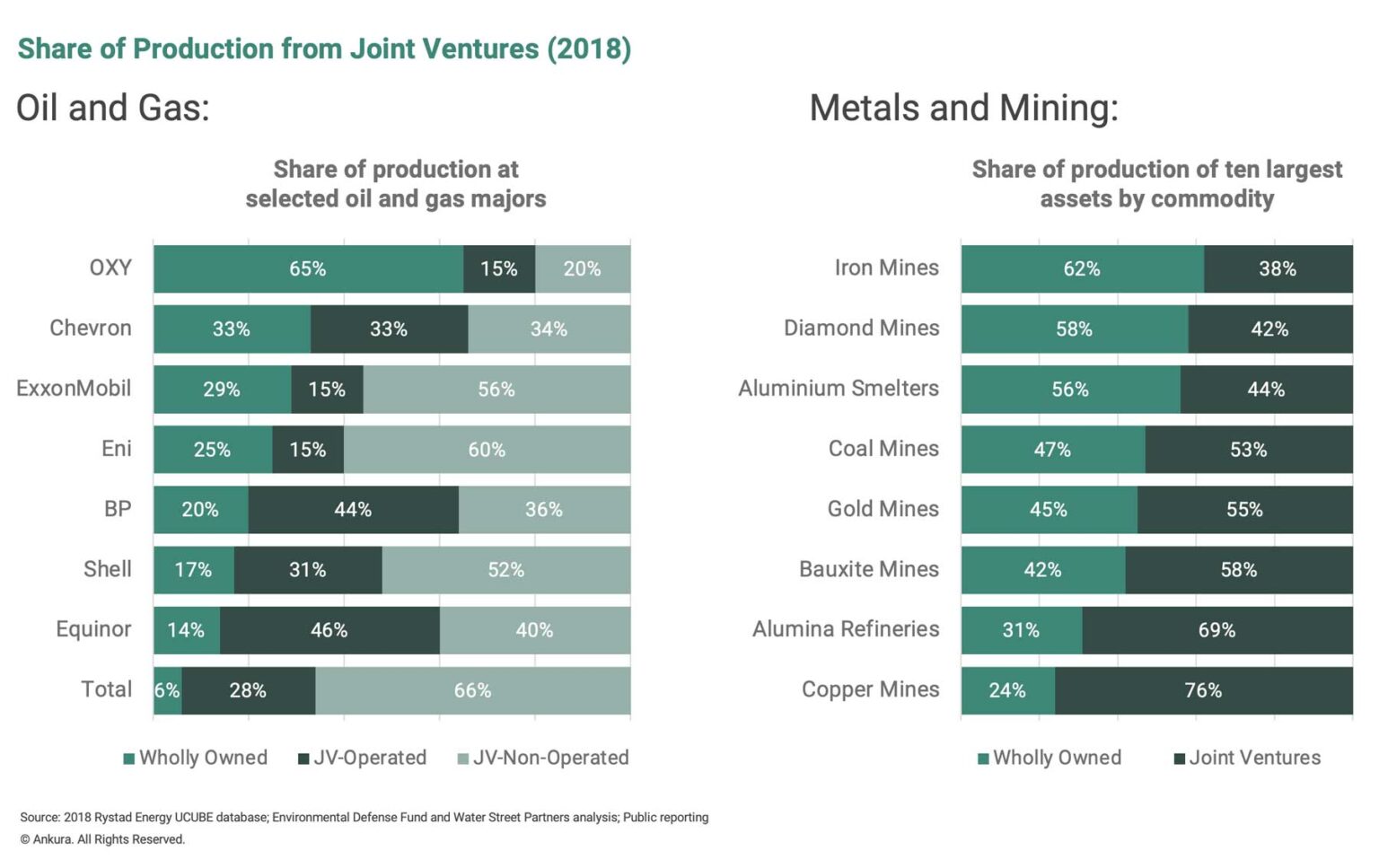

If joint ventures were extremely rare or amounted to a rounding error on the financial statements of natural resource companies, perhaps this would be okay. But JVs account for a material share of the assets, production, revenues, costs, and profits of many natural resource companies. For instance, 66-94% of current upstream production of the largest international oil companies currently comes from joint ventures, while in the mining industry 38-76% of the production in the ten largest assets in key commodity asset classes is from joint ventures (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: Importance of JVs to Natural Resource Industry

s to Natural Resource Industry" loading="lazy" >

s to Natural Resource Industry" loading="lazy" >

This means the clarity gap must be closed. And because joint ventures are structured in many different ways with operators of varying levels of risk maturity, how that clarity gap is closed can look very different.

DEFINING A COHERENT AND STREAMLINED MODEL

To help companies understand how to think about and effectively apply the three lines of defense in joint ventures, it is necessary to look at different situations based on the joint venture operating model and maturity of the operator. The most common situations requiring different approaches are (i) Mature partner-operated JVs; (ii) Mature independently-operated JVs; and (iii) Less mature JVs.

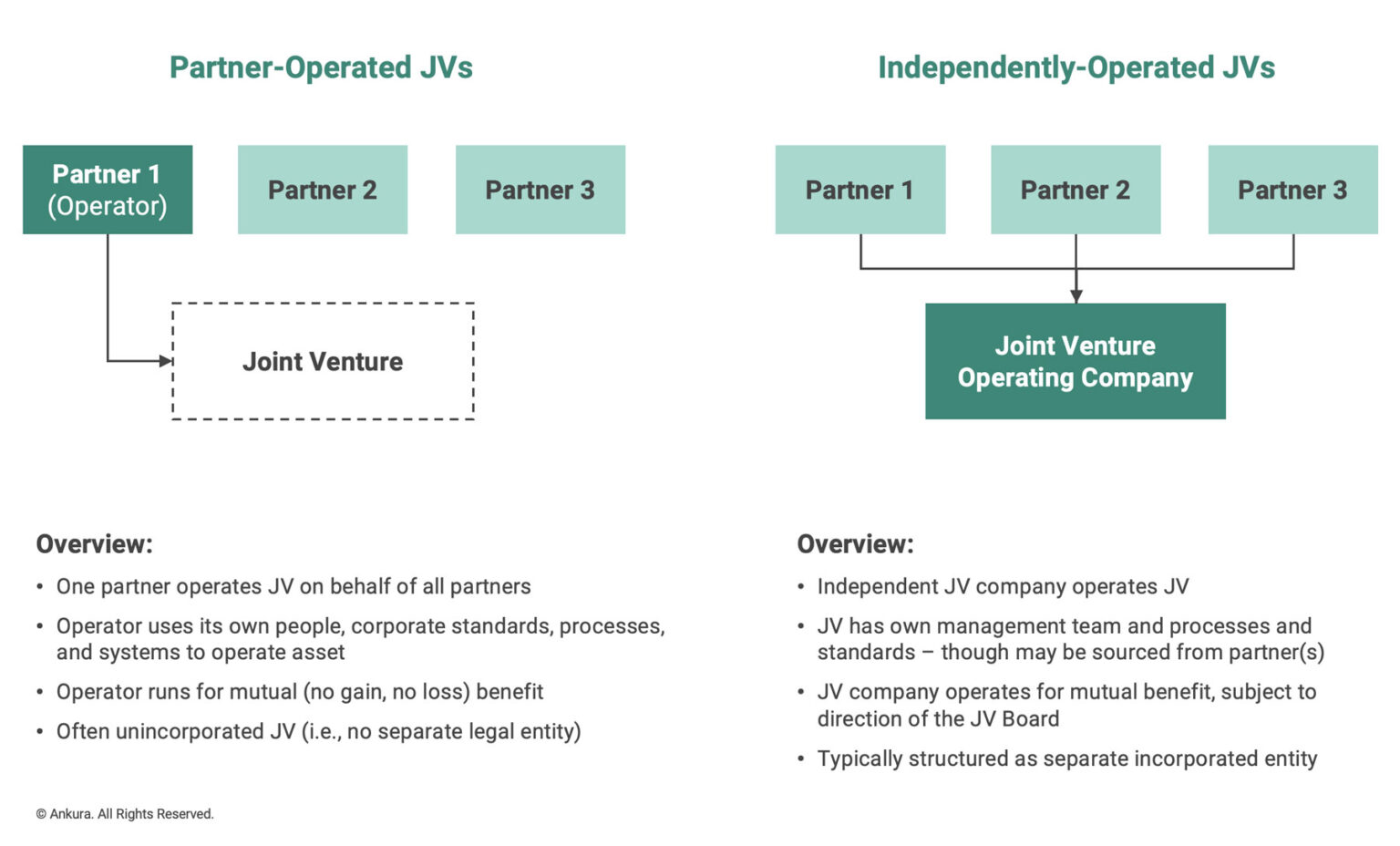

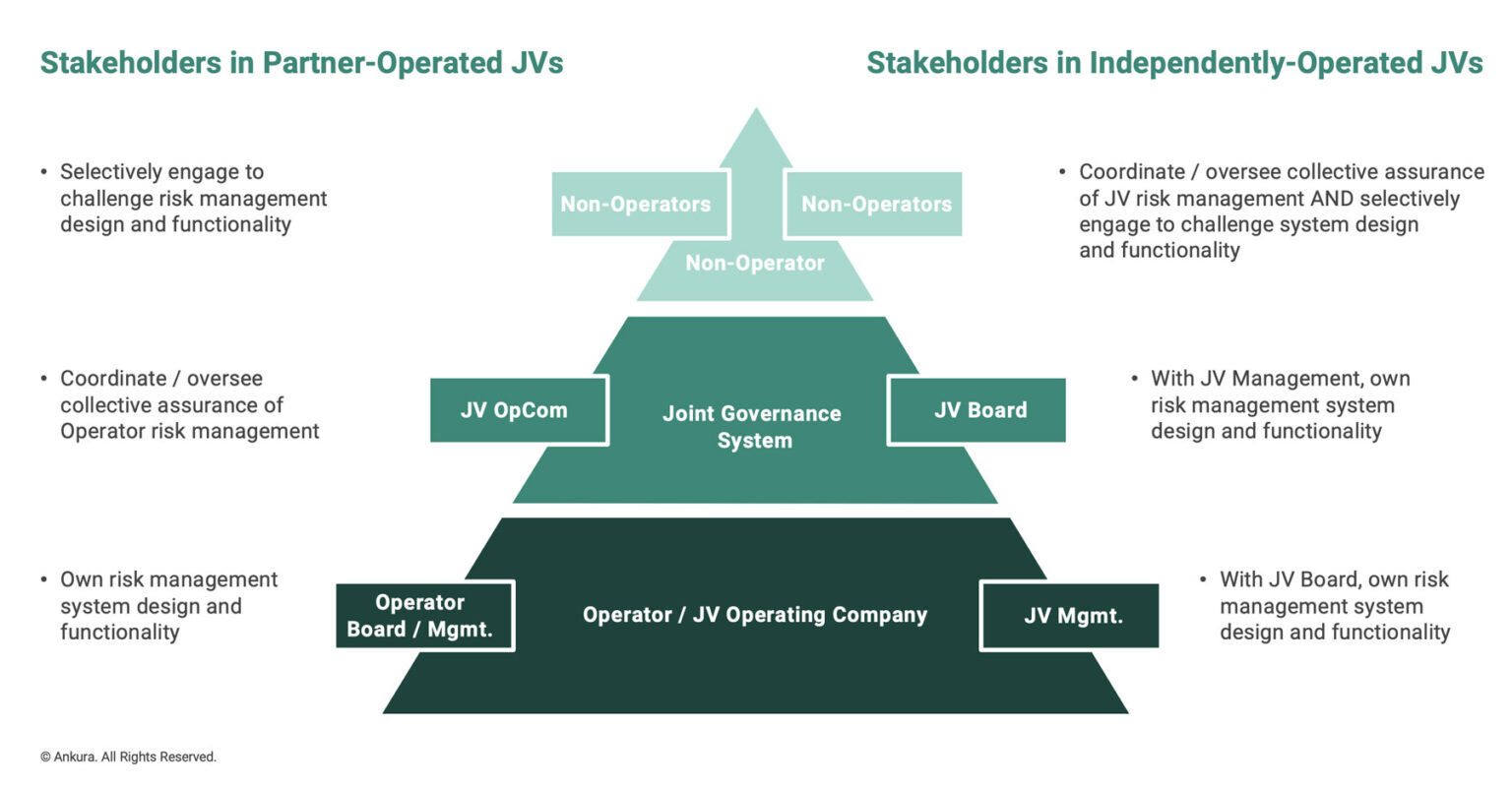

Mature Partner-Operated JVs. Clarifying the Three Lines of Defense model is perhaps least complicated for JVs operated by an experienced and highly-capable partner. This is the most common model in upstream oil and gas, as well other sectors, such as pipelines, storage terminals, and aviation fuels.[6]These JVs tend to be unincorporated partnerships defined by a Joint Operating Agreement (JOA) with an Operating Committee as the primary governance body; in some cases, they are incorporated … Continue reading In this case, the operator’s own internal lines of defense should be seen as a nested “first line” – with the operator having its own risk management policies, processes, and systems, leveraging its own functions and internal audit team to manage risks, and accountable to its own Board and regulators as key stakeholders. (Exhibit 2).

Under this model, the joint governance system should then act as a “second line” of defense, using various sub-committees and sub-committee members, working groups and site visits, and joint audits as a sort of backstop to provide the non-operators (via the JV Operating Committee or JV Board and their members as the key stakeholder) with coordinated and collective assurance that the operator’s risk management approach is effective and functioning, in alignment with all requirements in the legal agreements. For this to work, the partners will need to agree on the level of access and transparency provided by the operator, the methods for requesting information, the cadence of interaction between risk management and audit functions of the partners, and how the partners themselves will coordinate their work to avoid overlap (e.g., by dividing up audit elements jointly and cross-sharing results).

Each individual non-operator then has the potential to serve as a “third line” of defense if needed or feasible, given contractual rights and their relationships with the 0perator. Here, non-operators (i.e., in the form of asset team members) would use bilateral engagements with the operator to provide themselves with an independent check on the other lines of defense, providing additional comfort to their own stakeholders. The depth of this effort is also likely to vary proportionately to the second line, i.e., a less-engaged governance system would drive individual non-operators to probe for significantly more detail, and vice versa. And, similar to the second line, it requires alignment between the operator and non-operators on how bilateral engagement works (e.g., level of access, processes for seeking information).

But not all JVs are operated by mature oil and gas majors, and so there are scenarios with other peculiarities and constraints that the Three Lines of Defense model might address.

Mature Independently-Operated JVs. A large set of natural resource JVs are not operated by a partner, but rather are independent JV companies operated by their own management team and staff (Exhibit 3). In these cases, there is no separate operator Board and executive team with ultimate responsibility for risk management oversight. Instead, the JV has its own executive team and CEO with frontline accountability, its own risk management function, and its own internal audit function – all separate from those of the partners. And the joint governance system – in the form of the JV Board – is the primary stakeholder overseeing risk management in the second line alongside the JV CEO and executive team, rather than taking a secondary assurance posture (Exhibit 4). This is more akin to the traditional model, without a partner running 3 lines of defense nested in the JV’s first line.

But because this is a JV, non-operators have a desire to be involved, and they typically have stronger contractual rights to do so with independently-operated JVs.[7]Most model form joint operating agreements are designed for a competent and experienced Operator to keep non-operators at an arms-length; stronger operator oversight is therefore a point of … Continue reading In these situations, they often become a much more engaged third line of defense, seeking coordinated and collective assurance that the JV’s risk management system is appropriately functioning (e.g., the work done by the joint governance system when a mature operator is running the venture). And this dialed-up involvement is rarely smooth.

Indeed, non-operator risk teams, whether from audit, HSE, risk management, compliance, or finance functions, tend to instinctively approach joint ventures as wholly-owned assets or businesses. This mindset means that they compare the joint venture to their own company’s standards, rather than the JV’s or independent industry standards. It also means that they approach assurance activities as a “audit” designed to clinically and dispassionately inventory gaps, and without a need to communicate in a way that builds trust, educates, or persuades the independent JV management team to change course. These scenarios are therefore critical opportunities for the non-operators to jointly align on how the lines of defense will work – and to include JV management in that alignment process, ensuring their needs are also met.

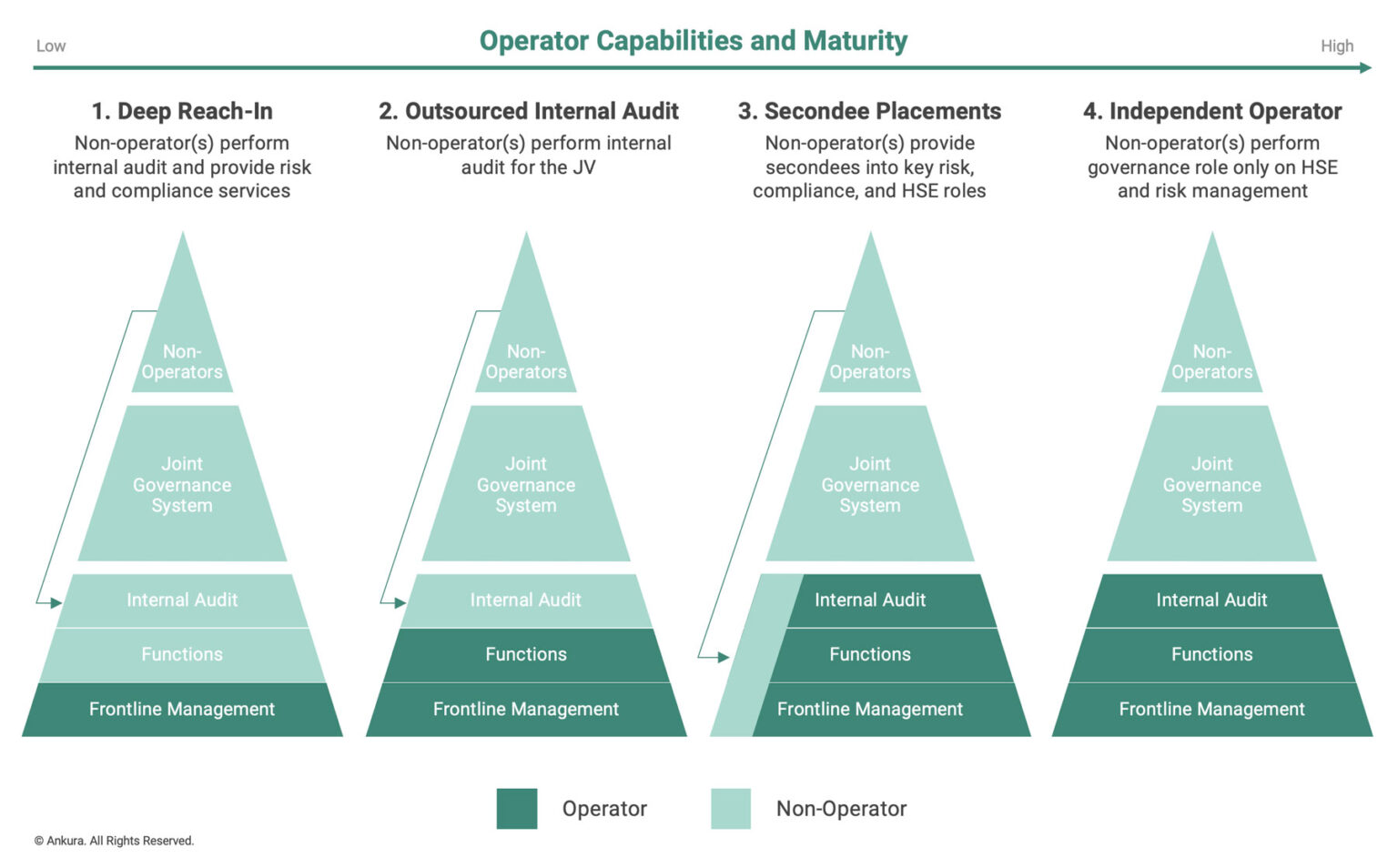

Less Mature JVs. While the prior examples described mature organizations capable of running a robust risk management process, not all JV operators are as mature in their approach to risk management. The least mature JVs – both partner-operated and independently-operated – address these gaps by adopting and utilizing the risk management systems of an owner and having the audit function be provided by an owner. Somewhat more mature JVs might use just one or the other, or nominally maintain their own capabilities while leveraging secondees and owner-provided services to support risk management (Exhibit 5). Each of these situations create complexities that need to be addressed.

For instance, when a non-operator is providing risk management systems or support to an independently-operated company, it inevitably increases the ties between the non-operator and the JV’s risk management functions. But how those ties are structured need to be clearly defined; if a non-operator provides a risk management system, for example, does that mean it will also audit the risk management system? And are the Board and other non-operators intending to step back and fully delegate oversight to the providing non-operator, or will they want to do their own double-checks that the JV’s risk system is fit for purpose and functioning as intended?

Similarly, when a JV has internal audit provided for it by a non-operator, what does that mean in practice? Who decides the timing and scope of each audit – and will each non-operator be able to audit anything it chooses, or should it be joint? Will the JV be audited to the somewhat different standards of each owner – or audited against some international approach (e.g., ISO 31000)? And what happens with the results – who has the power to drive change?

BRINGING RISK FRAMEWORKS TO LIFE

Designing a one-page conceptual pyramid is only the beginning of the discussion, rather than the end.

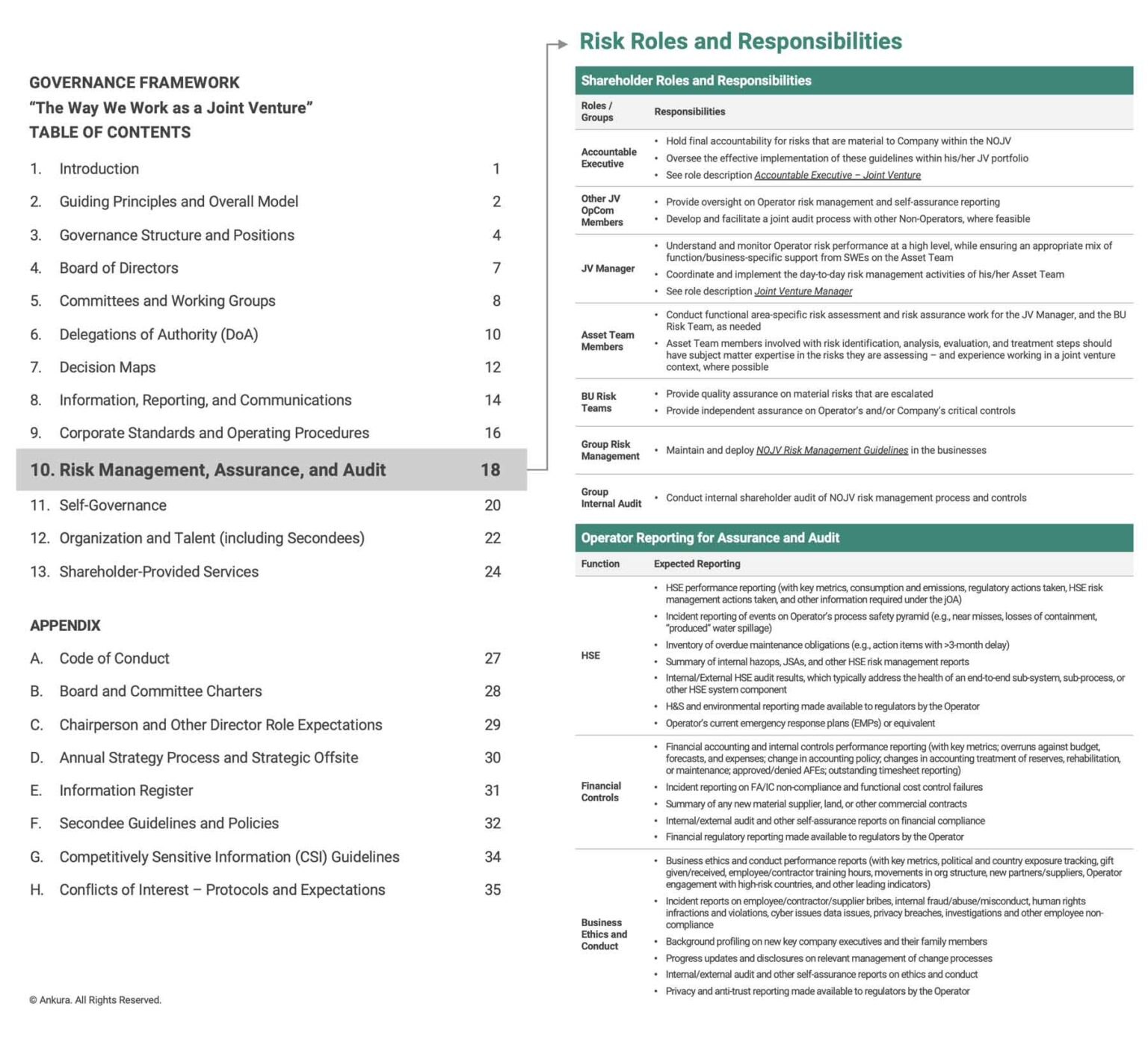

Ideally, the joint venture partners would use that concept as a springboard to fully flesh out and agree on their own three lines of defense model reflecting different partner capabilities and roles – and would include JV management in the conversation if an independently-operated JV. This effort would involve defining overarching principles, agreeing on the roles and responsibilities of the different lines of defense, and setting clear guardrails for how they relate to each other and also for how the non-operators relate to the operator. And it would also provide clarity on expectations for the how risk management works in the JV and how the JV would be audited for adherence.

This should all be included as part of a broader JV Governance Framework, which is a plain-language document that describes how the shareholders want to govern the JV and fills in the details absent from the typical JV agreement (Exhibit 6), but could be its own standalone Risk Management Framework in the absence of one.[8]James Bamford, “Operationalizing Joint Venture Governance,” The Joint Venture Exchange, August 2017

Whether the joint venture owners and Board define the Three Lines of Defense precisely as we have above – or agree on an alternate conception – such alignment is critical to create shared intent and coordination among different groups, and to ensure that neither gaps nor duplication in risk coverage exist.

Part two of this series focuses on closing other important risk-related gaps in operator due diligence, contract drafting, and ongoing governance.

Comments