May 2017— If you’re a JV CEO, you have a series of interactions with your owners across the course of the year. Some are planned and formal – regular Board and committee meetings, for instance. Others are informal – emails, one-off phone calls, and visits – to address specific issues or generally catch up. In most joint ventures, there is one meeting a year in which the CEO has the opportunity for a more strategic conversation with their owners – a chance to step back from the quarterly quizzing on financial and operating performance, and the press of recurring topics such as annual budgeting and compensation, to talk about and secure owner commitment on larger, more strategic issues that can fundamentally change the JV’s direction and performance.

We call this a critical conversation.

Enter your information to view the rest of this post.

"*" indicates required fields

CHARACTERISTICS OF CRITICAL CONVERSATIONS

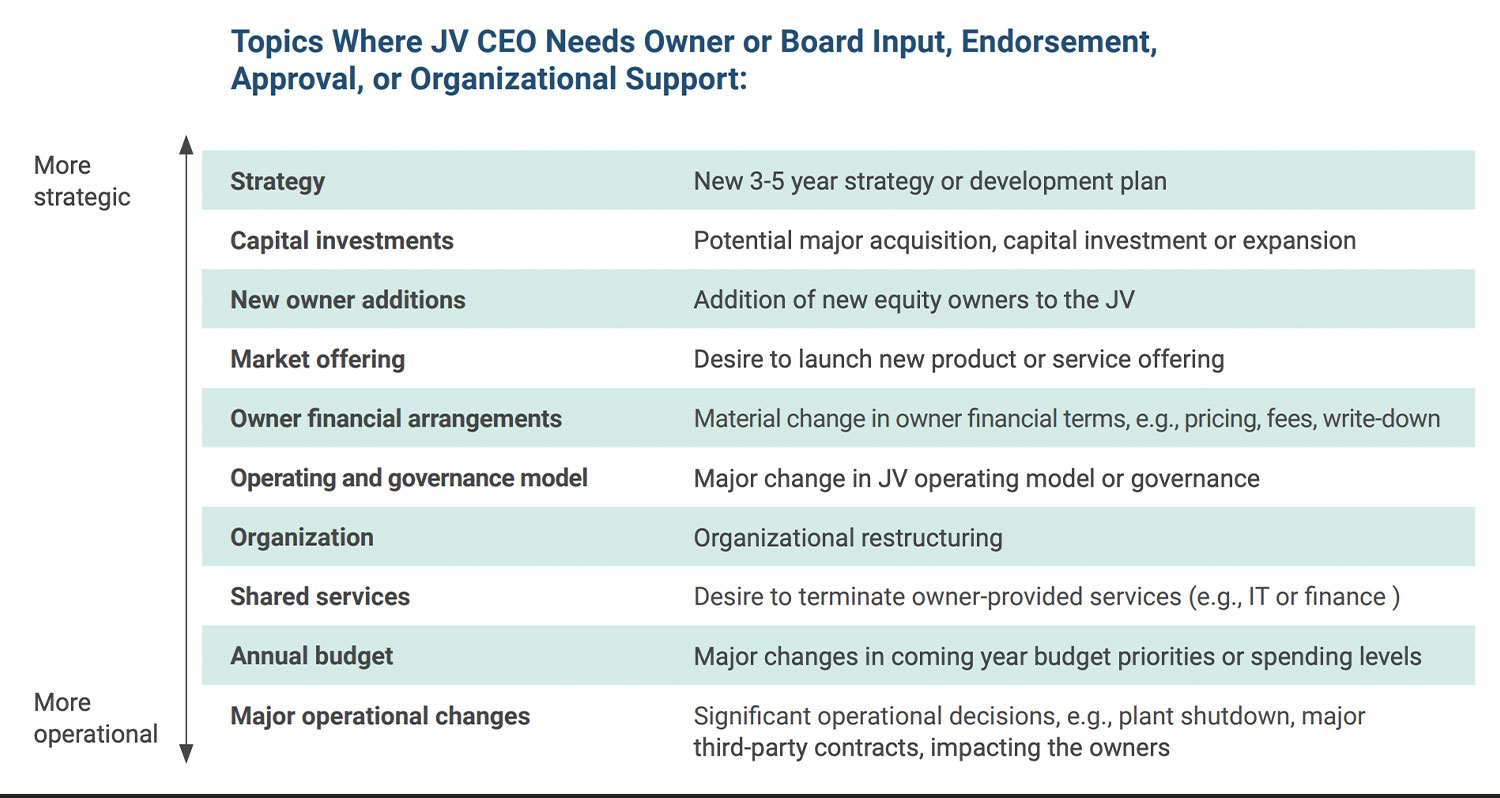

While every venture is different, the characteristics of these conversations share notable similarities. First, “big stuff” gets talked about – topics like long-term strategy, new product or market stepouts, a major investment or acquisition, a business model shift from being an owner-captive to a more market-facing entity, or a change in governance to enable more agility (Exhibit 1). Even seemingly routine topics, like the annual operating plan, can escalate into a critical conversation if major changes are being proposed.

Second, the time horizon is longer than other conversations, usually three to nine months to navigate a path to owner agreement, followed by implementation over a period of at least that length. Third, the issues raised require the owners to actively engage, approve, and buy-in to a course that differs from the status quo. The aim is more than a head-nod or polite applause. Rather, success requires the JV Board Directors and the owner organizations to take action – e.g., provide funding, give management freer rein, or secure internal approvals to allow the venture to move in a new way. And fourth, because of the above, these conversations require a higher level of preparation by the JV CEO.

JV CEOs also expose themselves to risks in advancing critical conversations. The matter may be sensitive. The owners may not be aligned. Changes may risk undermining current operations or bringing added work to the JV management team. Or the conversation may entail confronting the owners with underperformance of the business.

But the alternatives of not having the conversation, or not doing it well, are often worse.

In our experience, while JV Boards may not say so explicitly, they look to the JV CEO to lead them as a group – and expect CEOs to align the owners through a fog of differing ideas and interests. The safe roads of avoidance or not pushing too hard will mean the venture can continue on for another year, but that the business has missed a key moment to unlock a new growth idea, make a needed investment, or address a fundamental issue with the business. And when this happens, the JV typically fails to move apace with market, business, and owner needs. And sooner or later, performance suffers, and the CEO’s job may be in peril.

Why Is This So Hard?

Critical conversations are challenging. Our data shows 53% of JV CEOs struggle to secure alignment on a long-term strategy and evolution path for their venture, and 72% experience real difficulty in aligning their owners and Board on the JV’s medium-term plan. And more than 70% of JV CEOs stay in the role for three years or less – often because they struggle with these critical conversations and fail to meaningfully drive the business forward.

Several factors make these conversations structurally challenging. For starters, the owners may have fundamental misalignments outside of the JV CEO’s control and cannot be resolved solely in the boardroom. Additionally, with median JV Director tenure of just 30 months, high turnover on JV Boards puts a burden on management to bring all Directors up to a common base of understanding of the JV, which is needed prior to major decisions. High turnover also means that Directors often don’t have strong personal relationships with each other, or with the CEO. And many JV Directors have limited experience sitting on Boards and bring an operational mindset to the role – which makes strategic discussions difficult to keep on track.

Meanwhile, JV organizations are often thin on corporate functions, and rarely have well-staffed strategy, planning, finance, business development, or shareholder relations functions and few people with experience facilitating these types of conversations. At the same time, the prospect of major changes to the venture expands the universe of interested parties within the owner organizations to include corporate functions, shareholder reps, and adjacent business units, some of which may be annoyed or threatened by the proposal – and engage in fact-checking, problem-solving, behindthe-scenes critiquing, and commenting that can derail the discussion.

In about half of all JVs, the CEOs or other senior members of the management team are secondees, which creates at least the appearance of competing loyalties and conflict. Whether a secondee or not, a JV CEO must tread deftly in seeking owner input, guidance, and help in clarifying opinions and resolving issues. Go to one owner, and a CEO risks appearing to favor that company. Go to all the owners together, and risk receiving feedback that is so vanilla that it’s unhelpful. Go to each owner separately, and risk receiving conflicting guidance.

Indeed, JV CEOs can be surprised that the owners have already discussed – and started to frame an answer for – a strategic issue during a meeting where the CEO was not present or even aware the meeting was occurring. When that happens, the JV CEO has lost control of the narrative and an ability to lead the business.

But JV CEOs themselves are not without culpability. Many lack self-awareness. Many are not as good in these meetings as they think they are. Materials presented to the Board are not well prepared, or do not meet the analytical or clarity bar that Board members have come to expect from their own, admittedly larger, organizations. This is especially true when it comes to strategy and business model conversations – as one of those relating to key enablers such as the operating model or governance – where JV CEO and management teams lack distinctive skills. And many JV CEOs are not strategic in how they plot, syndicate, and build alignment prior to these conversations. To be blunt: Board dysfunction and lack of honest Board feedback to CEOs offers an easy excuse for JV CEOs to avoid taking a hard look in the mirror about how they approach these conversations.

Is Your JV Actually Ready?

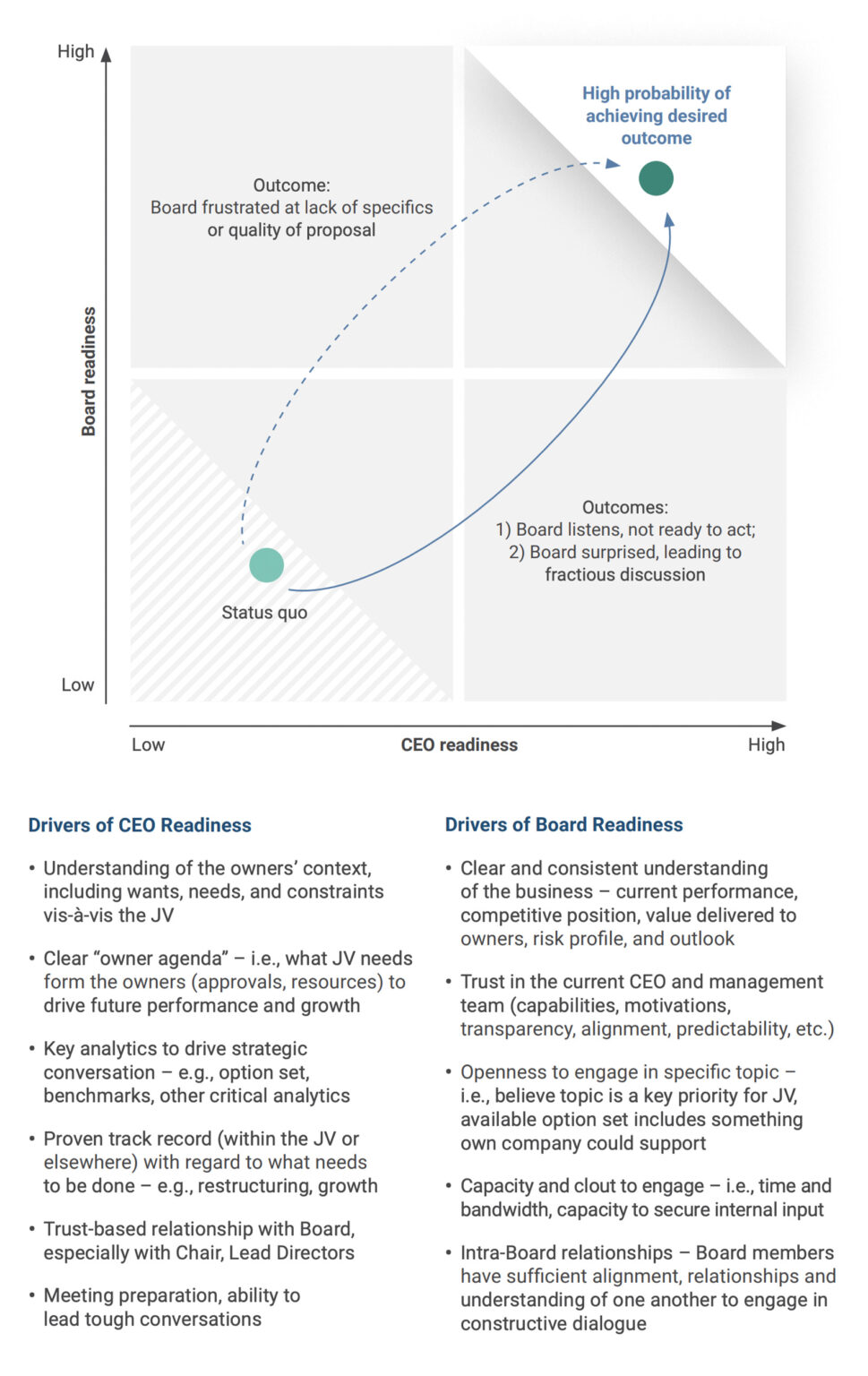

Dimensions of readiness: Having witnessed many critical conversations – some successful, some extremely challenging, a few leading to raised voices and finger pointing in the boardroom – we believe that great conversations happen when a JV scores high on two dimensions of “readiness” (Exhibit 2).

- CEO readiness: CEOs are ready for a critical conversation when they actually understand what the owners want and expect from the venture, and integrate that with the venture’s own business needs. CEOs are ready when they have a realistic grasp of the owners’ perceptions of JV performance and management capabilities and capacity. CEOs are ready when they have conducted various input and “prewire” pre-discussions to set up the collective conversation. They are ready when their team has developed high-quality analytics – often including options and recommendations – to support owner decision-making. And ready CEOs have built relationships with key Board members, especially the Chair or Lead Directors.

- Board readiness: Boards are ready when they hold an accurate and common understanding of the JV – its performance, risks, value delivered to the owners, competitive landscape, and prospects. Boards are ready when they have trust in the CEO and management team, including a belief that management is capable of stewarding owner resources. Boards are ready when Directors have functional relationships with one another and collectively, and thus are able to have open and honest conversation about strategic interests, constraints, trade-offs, and uneven costs or benefits.

Few JV CEOs enter the critical conversation in the top right corner of the gameboard. For most JV CEOs, the starting point is somewhere else – and the best of them chess-move their way to the top right corner prior to having the collective conversation. The journey will likely take several months, require restraint and pacing, and draw deeply on reservoirs of strategic, political, and operational skills from both the CEO and management team.

Examples of unreadiness: Many times, though, JV CEOs and management teams have the conversation somewhere short of needed readiness. The CEO of a healthcare JV entered such a conversation having developed what he thought was a compelling strategy for the business, which leveraged the unique capabilities and market position of the venture to enter new domains. But the conversation floundered because he kept the discussion at too high a level, so the owners were not able to see how that strategy would directly help each of their companies, or where the proposed strategy might overlap with initiatives that were already being cooked up in the owner’s organizations. Because some owners saw limited value to their companies, while others quietly had their own plans for these markets, the proposed strategy was dead on arrival. Yes, the Board members listened politely and asked questions, but they had no intention of supporting spending plans or adopting the new products – key enablers for the strategy.

A year later, the JV Board expressed dissatisfaction with where the JV was headed and asked for a major re-look at strategy. Meanwhile, the JV had lost time while competitors invested and bought “fold-in” acquisitions to enter the targeted markets.

Other times, the Board is not prepared – and finds a strong push for change unwelcome, even if the JV CEO is totally ready for the discussion. This form of unreadiness was on pointed display in a downstream oil JV. Eager to improve performance of the business through cost reductions, the JV CEO structured several hours of the annual Board Offsite to share his team’s plan for cost-cutting. This plan included terminating a number of administrative shared service contracts with one of the owners, totaling several tens of millions of dollars per year, and replacing them with substantially cheaper third-party providers. By providing cost benchmarking data, the CEO made clear just how expensive those owner-provided services were. But he inadvertently undermined trust between the owners, which then made agreement on other decisions much harder to come by. He also threatened his own employment status. Immediately after the Board meeting, the senior Director from the owner providing services pulled the CEO aside and said “Don’t you ever do that again. That is a matter between you and me – not a matter for our other owner.”

Getting The Critical Conversation Right

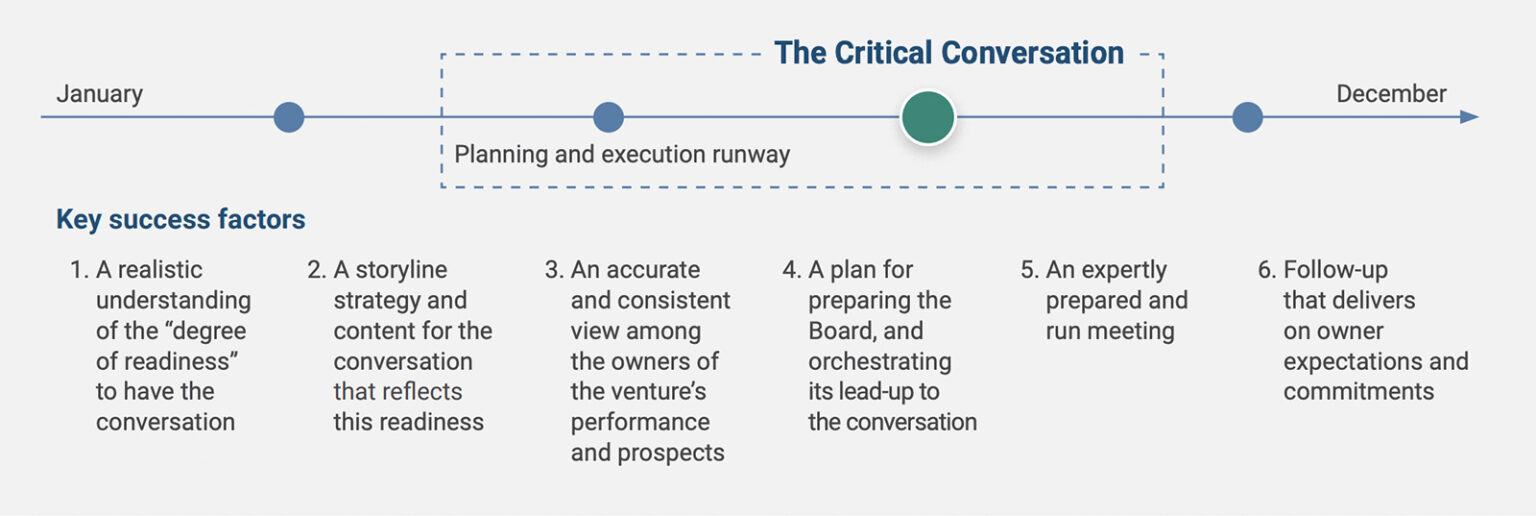

How can JV CEOs enter these critical conversations with confidence, and get to yes? Our work shows that the best JV CEOs tend to get six things right leading up to, and through, a critical conversation (Exhibit 3).

1) A realistic understanding of the “degree of readiness” to have the conversation.

First, great JV CEOs have a clear sense of what the JV needs from the owners, and what the owners need and expect from the JV. Great JV CEOs understand how to quickly sift and sort a potentially long list of owner issues based on value, risk, feasibility, and other factors to determine what should be on this year’s “owner agenda.” They know how to bundle issues to optimize the time with the Board and other owner executives to secure the agreement they need. And they know which issues require a collective conversation, and which can be handled on a bilateral basis.

Most importantly, they understand the degree of readiness to have the conversation and whether the owners need to have a different conversation before having the one the CEO wants. For example, in a supply chain optimization JV, the CEO wanted to get the Board’s permission to pursue M&A opportunities in a consolidating market, but realized that the Board needed to first understand the venture’s strategy to evaluate the opportunities against. This meant delaying the M&A discussion for three months while the management team, with the help of outside consultants, developed that strategy at a level of analytical rigor and clarity that the Board members required within their own companies.

Similarly, in a multi-billion dollar oil industry pipeline JV that was experiencing significant delays and cost over-runs, the CEO wanted to get the owners to agree to restructure the operating model to make the venture more autonomous and less vulnerable to owner company “operational overreach.” But the CEO realized that the owners weren’t ready to have that conversation – which included clipping back committees and technical service agreements – until the JV CEO made changes on the management team and demonstrated that the venture possessed the capabilities to deliver the project.

The best way to assess Board readiness is to canvass the owners. Typically, JV CEOs do this informally through one-on-one discussions with Board members and other owner executives, eliciting opinions, and testing ideas. It also requires some delicately-run group discussions to collectively align on the need to introduce the issue. But increasingly, we also see JV CEOs supplement these conversations with other data-gathering tools.

By surveying the Board and other key stakeholders in the owner organizations, including functions and business units that interact with the venture, the JV CEO is able generate a broader and structured fact-base to determine levels of alignment, uncover key sticking points, test solution spaces, and generate data that might unlock a conversation.

For example, in a four-partner financial services JV, the CEO annually sponsors a Voice of the Owners Survey. This survey is sent to 40-50 people within the owner companies, including Board members and key functional staff who work with the JV. The survey asks about JV performance, and satisfaction with the venture on joint product development and marketing, and other initiatives. A version of the survey sent to the Board also includes questions about Board and committee performance, which were used in an annual discussion about governance health. Last year, the survey also tested owner views on a dozen potential strategic growth initiatives, which were the focus on the August Board Retreat.

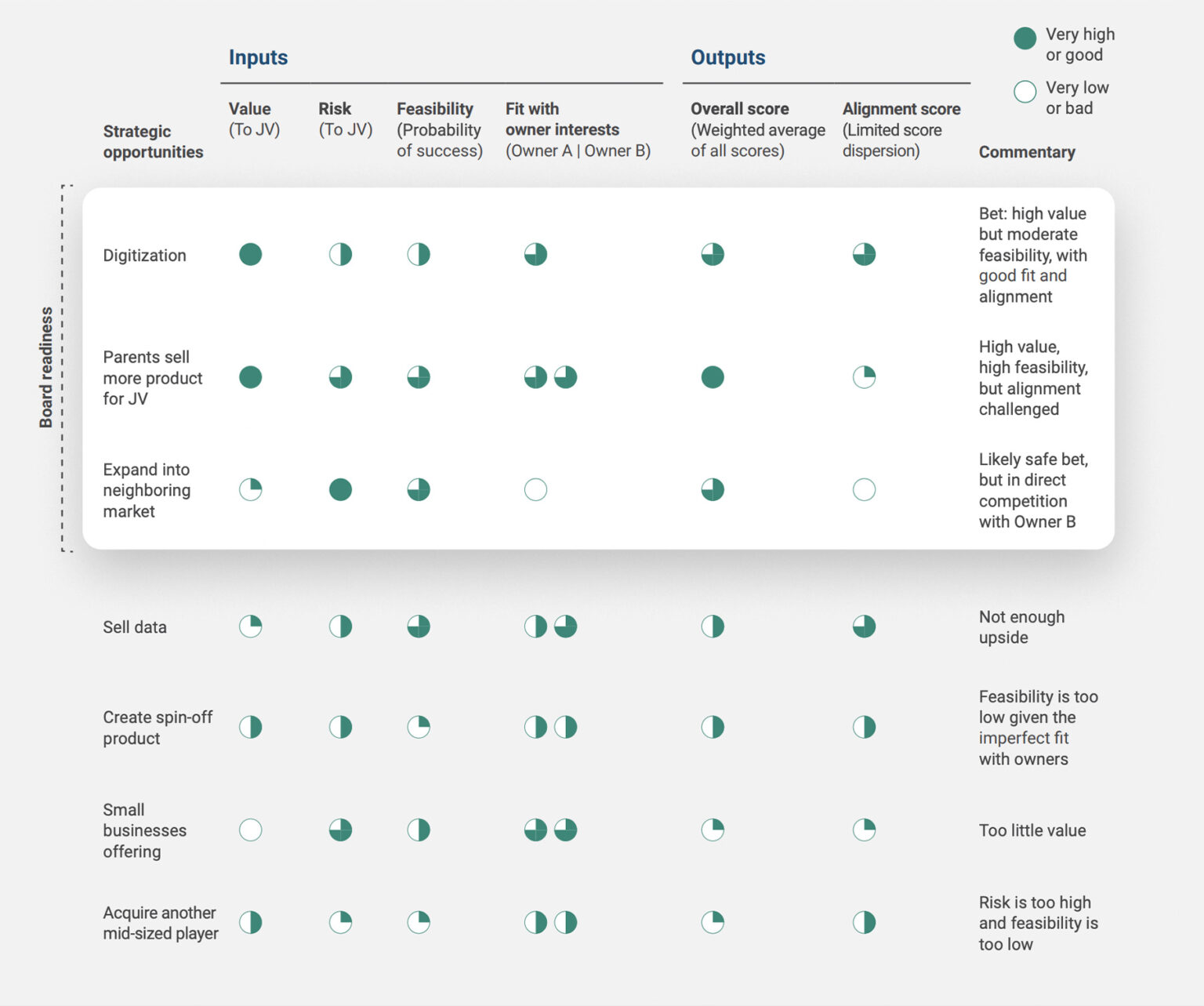

At the highest level, the readout showed the owners’ ingoing views about each new segment idea with regard to its potential value, risk, feasibility, and fit with their own strategy (Exhibit 4). The summary readout also showed overall and alignment scores – the latter of which indicated the similarity, or clustering, of owner answers. This readout complemented other data, including testing owner understanding of different initiatives and views of management performance in articulating the case so far. All of this provided the JV CEO with an invaluable map for how to approach the growth conversation – including which initiatives to focus on vs. not, and the nature of resistance for individual initiatives – and data which could be used in the conversation itself.

Exhibit 4: Voice of the Owners Analysis — Strategic Opportunities Summary

©Ankura. All Rights Reserved

2) A “storyline strategy” for the conversation that reflects this degree of readiness.

At its core, scoping a critical conversation in a JV is about deciding how to flow, and what to include in, the discussion.

In our experience, there are six ways to structure any such conversation (Exhibit 5), which can be arrayed based on how close or far the JV CEO comes to presenting a single-point solution to the owners.

Indeed, the six story-lining strategies provide JV CEOs their own version of Dante’s Inferno. Approach 1 is akin to the first ring of hell, the closest to life above ground. It is where JV Boards act most like Corporate Boards, reviewing and approving plans of the CEO, whom they trust to carry the business forward. In contrast, Approach 6 lies deepest into the earth, where the ascent out will be a long and laborious climb, where the sunlight of tangible progress lies the farthest away. But it may be where the CEO must start – because beginning anywhere else will fail to create the needed environment for change.

Approach 1, where JV CEOs lead with one solution and a plan to implement it, offers the fastest path to progress, as it minimizes alternatives and downplays discussions about other opportunities, broader market context, and any underlying gaps or risks to the business. The aim of this approach is to get the owners to agree – both to the solution and the plan needed to deliver it, including required commitments from the owners. This approach offers great temptation to many JV CEOs. But it is often not the right one.

Approach 6 is about confronting the owners with the status quo – presenting fact-based and specific gaps, problems, and risks to the business that the owners must understand and confront. In one energy JV, the CEO confronted the owners with a production decline curve that dropped off a cliff in eight years. He also presented a list of 20-plus asset-life-extending capital investments that had been proposed in the last decade but rejected by the owners. And he showed increasing attrition among management and senior technical staff, which he attributed to employee concerns about future careers. He challenged the owners to stop pretending the business was fine – and to confront their own companies’ historic failure to do anything, or allow anything to be done, about it. This then led the owners to be ready to accept other approaches – including having a discussion about opportunities, looking at options with the best of those opportunities, and finally agreeing to certain solutions to address the issues.

None of these six approaches is right in all situations, as JV CEOs find themselves in different levels of their own hell. Rather, great JV CEOs choose an approach that reflects the venture’s situation – and they switch approaches, and climb down or up based on new information about owner readiness to have the conversation.

3) An accurate and consistent view of JV performance and potential among owners.

Great JV CEOs earn the right to have critical conversations by developing an analytically sound, visually compelling, and integrated picture of the JV’s performance, risks, and prospects. We think of this as the JV equivalent of an Investor Presentation. Without this, JV owners lack an accurate and shared basis for taking collective decisions.

Exhibit 5: Structure Critical JV Conversations

APPROACH 1: Single Solution-Led

Overview:

- JV CEO leads conversation around a proposed solution and plan related to specific opportunity or issue, with conversation oriented toward a “yes or no” answer from owners

- Limited time spent on business context, performance, gaps, threats, options/alternatives, etc.

- May leverage owner survey data to show alignment

- JV CEO outlines implementation – key actions, resourcing requirements (including those from owners so that owners know what they are signing up for)

When to Use:

Owners understand venture performance, risks, and prospects; are generally aligned on the issue; and have history with one another

APPROACH 2: Options with Preference-Led

Overview:

- JV CEO organizes conversation around set of options to address opportunity or issue – and includes own view of preferred option

- Some time spent framing opportunity, broader context

- May use original intent, guiding principles, pre-meeting owner input to assess different options

- JV CEO uses conversation to secure guidance from owners – and, depending on discussion, attempt to get directional agreement to proceed

When to Use:

Owners understand venture performance, risks, and prospects; have a grasp of the issue or opportunity; and are likely to be aligned on the answer, but have not had a chance to discuss or fully align

APPROACH 3: Options-Led

Overview:

- JV CEO organizes conversation around slate of potential options to address opportunity or issues – and simply facilitates discussion on owner preferences

- Some time spent framing opportunity, broader context

- JV CEO then uses conversation to secure guidance on and/or refine options, sharpen assessment criteria and analytics required to take decision

When to Use:

Owners understand venture performance, risks, and prospects; but do not understand or likely hold different ingoing opinions about how to address the opportunity or issue

APPROACH 4: Range of Opportunities-Led

Overview:

- JV CEO frames discussion based on untapped potential of the business, and presents range of opportunities to achieve:

- For each opportunity, presents summary description, upside potential, risks, initial assessment

- Opportunities may be growth and/or performance turnaround initiatives

- JV CEO then facilitates discussion to winnow down opportunities, and secure endorsement to flesh out or pursue

When to Use:

Owners understand venture performance, risks, and general prospects, but lack integrated view of the range of opportunities and issues for JV to advance to next level

APPROACH 5: Market Context-Led

Overview:

- JV CEO leads with a structured and analytical discussion of broader market and competitive landscape, including:

- Customer and technology changes

- Regulatory and stakeholder changes

- Competitor moves

- Parent company changes

- Company positioning

- Company and market risks

- JV CEO then uses conversation to secure guidance on JV, and then presents opportunities and solutions in the context of this market environment

When to Use:

Owners lack up-to-date or aligned understanding of business, its market, performance, risks, and prospects – i.e., due to Board turnover, incomplete analysis provided by management

APPROACH 6: Gaps- and Threats-Led

Overview:

- JV CEO “confronts owners with status quo” – leads with a fact-based, objective, and specific recitation of gaps and/or risks business, including:

- Gap to historic performance*

- Gap to peers* (3rd party or owners)

- Gap to initial business plan

- Gap to regulatory requirement

- Threat of competitors

- Threat of business decline

- JV CEO presents solution(s) to owners in context of addressing specific gaps, threats

When to Use:

- JV is stuck – and resistance to change is high among at least some owners

- Other conversation strategies have failed

* Gaps may be financial, operational, or HSE

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

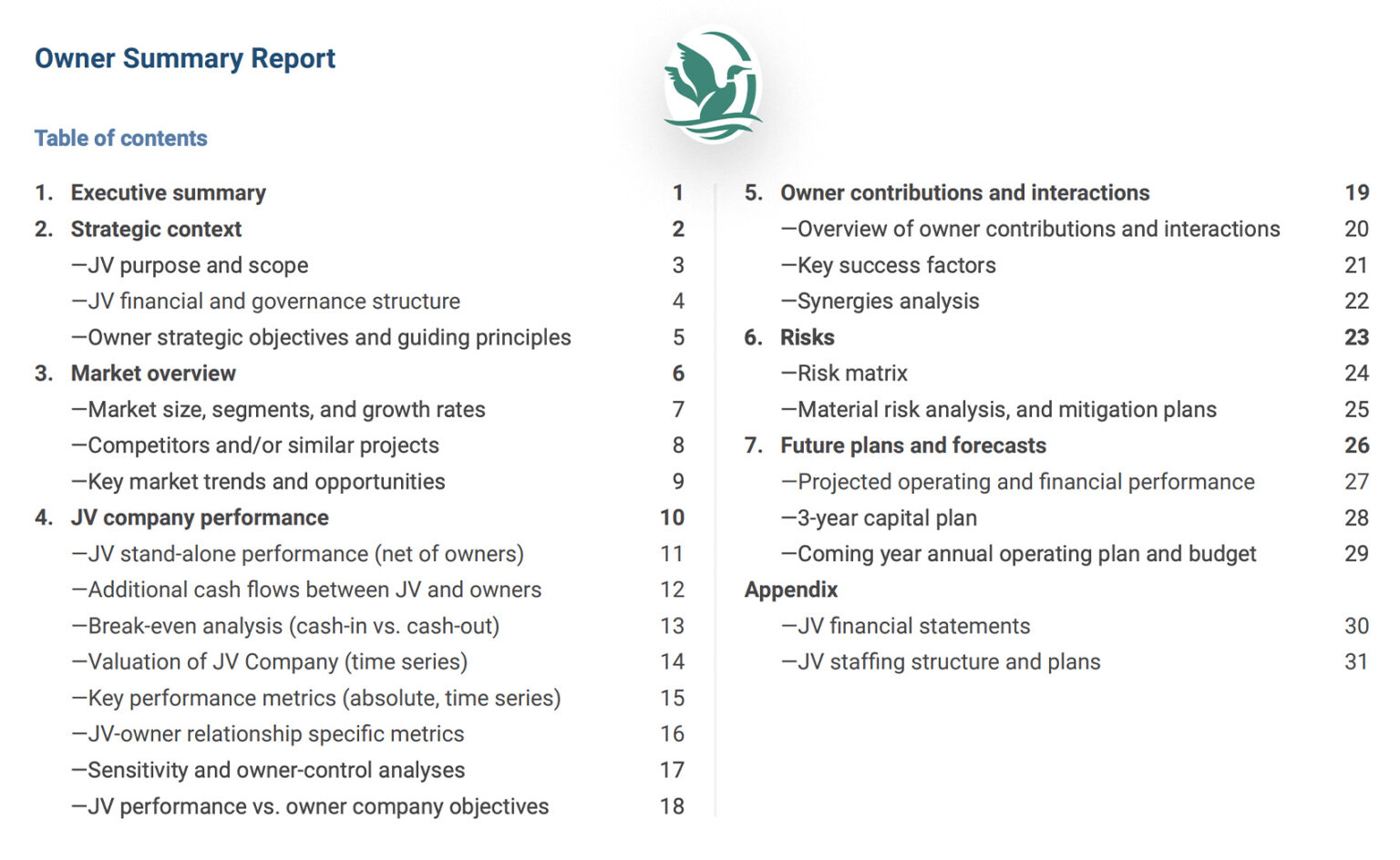

In our experience, this Investor-Quality Summary of the JV is short (15-30 pages) and includes both standard and non-standard reporting (Exhibit 6). This includes externally-facing analyses, such as operational benchmarks, market positioning, financial performance, and discussion of the future plans, prospects, and risks. The discussion on financial performance may include earnings per share that flow through to the owners, while the commentary on future prospects might include whether the JV is facing constrained growth because the initial authorized scope has been largely realized, and lacks the running room or capital to grow into adjacent domains.

Such an Investor-Quality Summary also includes certain unique JV content. This includes calibrating the JV’s performance relative to the owners’ initial objectives, not just their most recent goals. It encompasses tracking how the JV creates value to the owners outside the JV P&L (e.g., via operational synergies, service or license fees, cross-sales of other products). It might include monitoring owner contributions, including capabilities and other implicit contributions, which often provide the fuel to make the venture go. In many cases, JVs benefit from expanding the set of reported metrics to incorporate those that their owners and industry peers report to their investors, which may help the owners calibrate the venture, and implicitly sends a signal that the JV is a separate company of real standing, rather than a partially-owned business unit.

In an asset JV, this investor-quality presentation will include or take the form of an asset strategy or development plan – i.e., an up-to-date view of the resource, its potential, and different technical, investment, and regulatory strategies for optimizing the asset across its life. In many independently-managed mining and upstream oil and gas JVs, such asset development plans lack needed analytical rigor, fail to incorporate key information, or do not adequately reflect owner views of the asset.

This makes it difficult for the JV CEO to successful drive a critical conversation. For example, in a large mining JV, the JV CEO has been advocating for a $1b capital expansion. Largely outside the CEO’s view, one of the owners had spent six months conducting a detailed risk and opportunity assessment of the asset, which concluded that while the asset remained one of the largest and lowest-cost mines in the world, expansion looked to be technically and legally much more challenging than the current management model implied.

So, at the very moment the JV CEO was preparing a conversation with his owners about investing in that expansion, one of the owners was about to tell management to fundamentally overturn its plans and shift to operational optimization. That looming collision would have been avoided if management had worked closely with its owners’ technical and asset modeling teams to develop a shared view of the asset.

4) A basic process roadmap and tools to orchestrate the build-up to the conversation to ensure needed owner understanding and conceptual buy-in.

Great JV CEOs know how to scope and orchestrate their way to a critical conversation. This is process strategy of the highest order. Such orchestration skills include defining what warm-up or pre-conversations to have with whom, when, where, and about what in advance of the big conversation, including informally testing emerging solution sets.

In our experience, JV CEOs often make several missteps here. This includes having the collective conversation too soon and targeting just one conversation and “going for the close,” rather than strategically using other meetings to introduce concepts and directly and indirectly build the case for change. Another common misstep is to allow the shareholder reps in the owner organizations to carry the messages back to their organizations, rather than having direct personal discussions with Board members or other senior decision-makers.

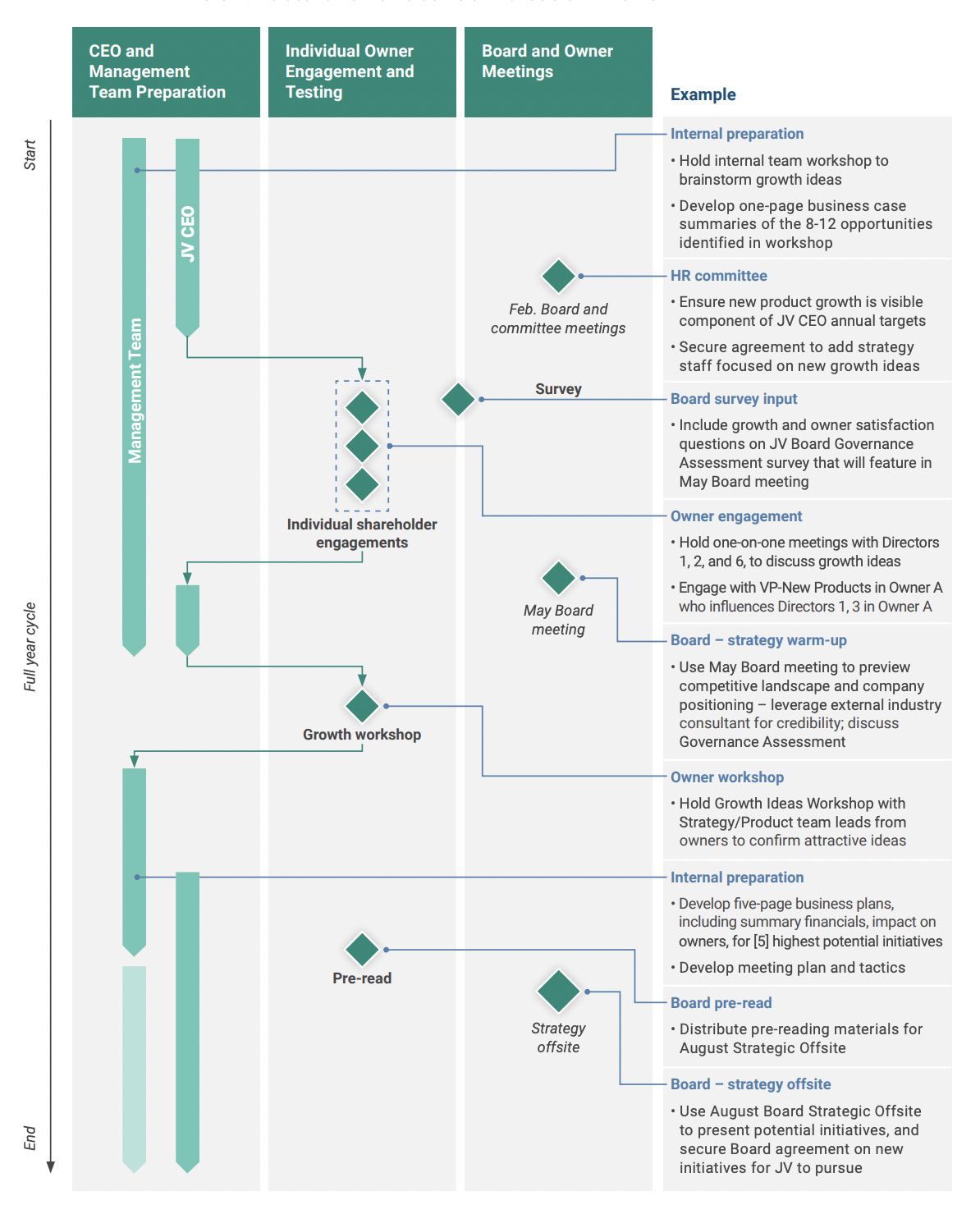

Indeed, the best CEOs overlay the basic staging of the critical conversation onto the JV’s annual governance calendar. For example, the CEO of a financial services JV created a supplemental view of the annual governance calendar that focused on what was needed to have a great conversation with his owners about new growth initiatives (Exhibit 7) – a conversation that he planned for the August Offsite. This version of the annual calendar differentiated between and dovetailed the work of management with owner engagement activities, whether that be through preplanned Board and committee meetings or less formal one-on-one and group interactions with the owners. It also included securing key “seals of approval” from internal product leads and a leading strategy consulting firm.

In a five-member “utility-style” JV historically focused on one industry, the JV CEO adopted what he referred to as a “drip, drip, drip” approach to creating Board readiness. Rather than spring a big strategy discussion on his Board at the June Board Offsite, he structured each of the prior four Board meetings to include a standing agenda item on growth. Unless pressed for time, that module included a quick update on the three to five growth initiatives that management was incubating. Specifically, he presented one-page summaries of each initiative, including an overview of the segment and why it is interesting, and current status of ongoing work.

This prepared the ground for the more integrated discussion in June. Director comments and body language also gave the CEO clues and cues about how much owner appetite existed to make larger investments to enter these segments.

5) An expertly prepared and run meeting, including an agenda design, attendee group, and facilitation strategy that allows for decisions to be made.

Great JV CEOs know how to set up and run the big collective conversation. No matter whether this conversation occurs at a Board Strategic Offsite, a regular Board meeting, or other owner forum (e.g., CEO or Shareholder Summit), the basic principles are the same. The invite list needs to be actively curated and limited in number. Left unmanaged, individual JV Board members tend to invite venture managers and functional experts – a move which swells attendance to levels that make an actual conversation difficult and opens the floor to a group that can be the most capable naysayers, nitpickers, and general derailers. At the same time, the pre-reading material needs to be limited in volume and thoughtfully designed, with the explicit aim of advancing the conversation.

In our experience, it is rarely a good idea to “just send” the meeting presentation materials. Better to structure the pre-read to include the meeting objectives and agenda, certain content that provides the context for the conversation (e.g., company and industry competitive landscape), and, potentially, some thought-provoking additional reading.

The discussion needs to be scoped right, which often means avoiding an agenda that is too ambitious. In some cases, it is better to have a conversation unfold over two days – say, with a module on Day One providing contextual facts and describing opportunities and options, and a module on Day Two to take decisions. This allows for soak time and gives the CEO a chance to do mid-course syndicating and temperature-taking. It also allows the owners to align with others in their organizations prior to taking a decision – something a one-shot discussion cannot do.

The JV CEO will undoubtedly play a central role in running the meeting. But it is sometimes best for the CEO to leave the facilitation to an external facilitator and take a seat at the table as lead sponsor or participant. This positioning better allows the CEO to take in the mood and dynamics of the group and establishes an implied status as peer to the Board members and other senior shareholder executives in attendance.

This is not to suggest that the JV CEO should be neutral. Indeed, while counterinstinctual, JV CEOs generally need to advocate for a position, although how forcefully, quickly, specifically, and publicly to do so must be crafted to the context. Many inexperienced JV CEOs believe that since the owners “own” the company, their role is to frame issues and allow the owners to make decisions based on an accurate understanding of the facts and options. While there are a small set of issues that are truly owner matters (e.g., whether to pay a special dividend to allow one owner to get cash out of the company, or whether to adjust owner materials supply or offtake pricing from what was negotiated in the joint venture agreement), the voice of the CEO is highly relevant on the vast majority of issues, even if ultimately decided by the owners. The reason: the CEO is the one who best knows the business and more than anyone is concerned about the collective interests of the owners. Said differently: Public company CEOs do not sit neutrally before their Boards and shareholders; rather, they lead their companies, which includes guiding their Boards and shareholders to good decisions.

When structuring a collective conversation, the discussion itself needs to be designed to induce genuine engagement, not ritualistic agreement. This means rejecting the temptation to present a stream of data-filled slides and avoiding the urge to parade in multiple members of the JV management team to present a piece of the story. Managing the invisible currents in the room is critical to making real progress. In a six-partner cross-border venture, the JV CEO quietly coached his two most dominant Board members to hang back and avoid offering strong opinions early in the discussion, with the hope of hearing the opinions of the less vocal owners. Getting these invisible currents pointed in the right direction is a matter of preparation – for instance, lining up a couple of the most senior or influential Directors to seed the conversation to promote a good start.

6) Meeting follow-up that secures needed owner commitments.

Finally, great JV CEOs maintain the momentum from the conversation to drive change. Superficially, this includes all the elements of classic meeting follow-up: summarizing agreement reached, defining clear next steps, assigning individual accountabilities, securing needed resources, and tracking progress against agreed milestones. But great CEOs know that the JV structure introduces some unique twists into the art of the follow-up. Because owner alignment can be fleeting – and the successful implementation usually entails some action from various parts of the owner organizations which, by the way, the JV CEO does not control – the best JV CEOs use various best practices to memorialize and take advantage of alignment reached.

Such practices include securing some form of public commitment from senior owner executives immediately after the meeting – perhaps by drafting a “Board Communique” summarizing the discussion themes and agreed actions, and sent under the joint signatures of the senior owner executives or Chair. It also means quickly assembling venture employees to communicate the spirit, content, and outcomes of the conversation. Our research and client experience show that JV employees – especially second-level managers who work for the CEOs direct reports – tend to feel the most disconnected from the business. As a rule, they do not get invited to Board meetings or strategic offsites, and feel that discussions and decisions are happening outside their view. At the same time, they can be the ones who get the most thrashed around by owner requests and shifting positions, and from not understanding why the owners are preventing the venture from pursuing new initiatives. It is critical for the JV CEO to communicate directly and meaningfully with that group after the meeting.

Similarly, it can be helpful to have the Board involvement explicitly shift to a subset of Directors or a committee, which is empowered to monitor, tie down details, etc., instead of continuing to rely on the entire Board.

Download the PDF version of this article.

Getting to yes in critical conversations is not a game for the impatient, distracted, disorganized, or politically unsavvy. Indeed, it is process strategy of the highest order, requiring JV CEOs to achieve advanced levels of understanding of owner readiness to have these conversations, and to take deliberate steps to set up these conversations before they happen. In many ways, joint ventures are a “continuous negotiation” – among the owners, and between the owners and management. Getting the critical conversations right requires approaching these conversations with similar levels of strategic preparedness as a commercial negotiation.

Are you ready to be a critical conversationalist?