[Infographic] Independent Perspectives Prove Effective in Resolving JV Disputes

98% of disputes that have been referred to a dispute review board do not proceed to arbitration or litigation.

The Strategic Imperatives of Getting a JV Off the Ground

MARCH 2022 — A quarter century ago, companies awoke to the fact that success in M&A hinged on running a deliberate and well-orchestrated post-merger integration process. Serial acquirers like ABB, Cisco Systems, General Electric, Lloyds TSB, and Waste Management realized that there was a right way – and a wrong way – to integrate companies. They built detailed M&A integration processes, developed playbooks, captured learnings, and continuously improved their integration approaches.

In JVs, launch is every bit as important.

Our research shows that the trajectory of JV success is almost always established during launch planning and execution, and that mistakes made here can easily erode 30-50% of venture value.[1] The launch phase – beginning with the signing of a term sheet and continuing through the first 12-18 months of operation – is usually not managed closely enough. Missteps and omissions can result in delays, missed synergies, and failure to reach the full potential of the JV. They can also plant the seeds of strategic conflict among allied companies and enable a governance system marred by over-reach and dysfunction.

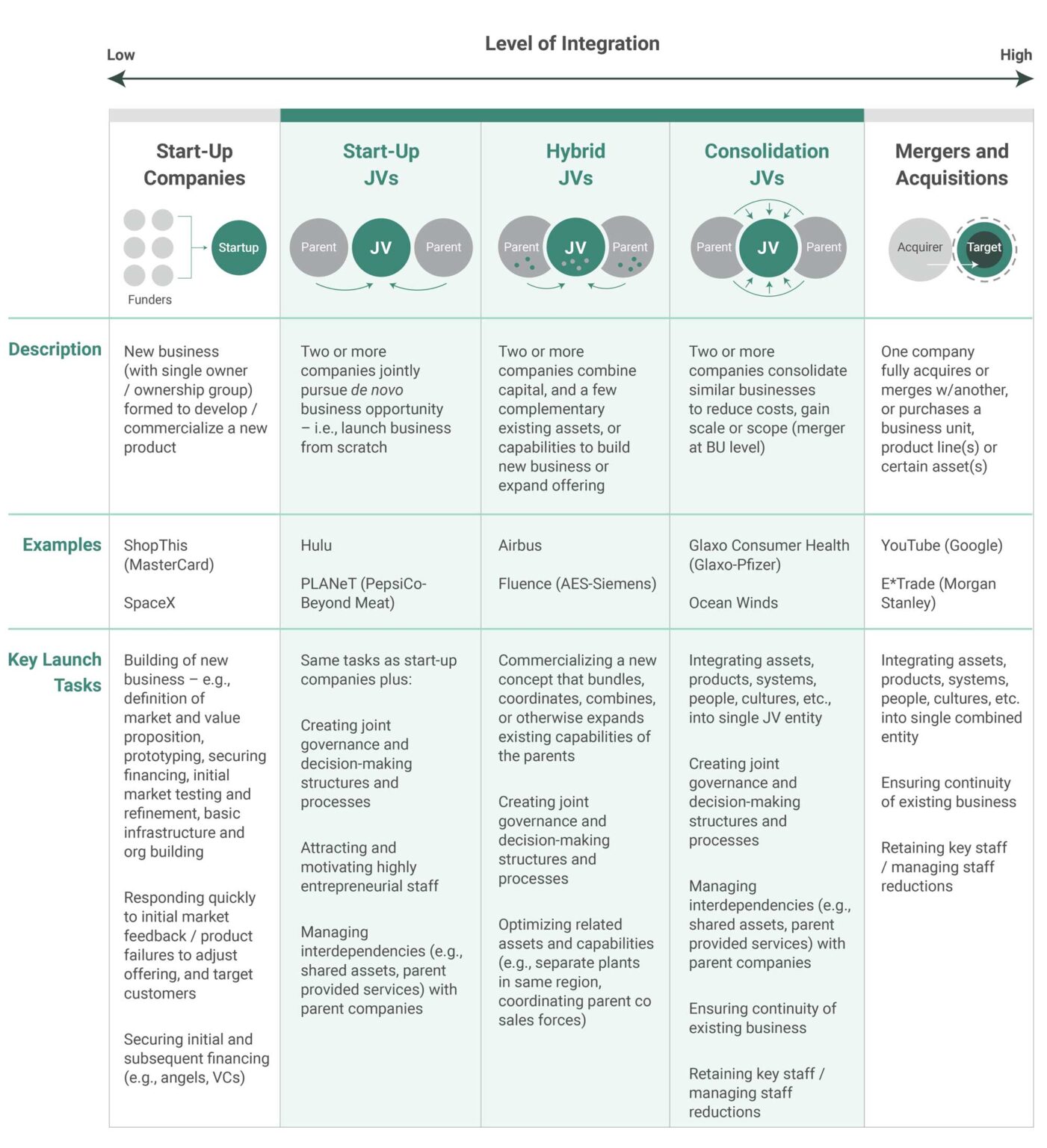

Launching a joint venture is a uniquely challenging endeavor, often introducing issues both common and additive to integrating an acquisition or starting a new wholly-owned business. Below, we discuss how launch varies by type of JV and share a few lessons we have learned over the years from helping clients operationalize JV legal agreements and launch new ventures.

"*" indicates required fields

Joint ventures come in different varieties – each with their own launch requirements (Exhibit 1). For example, launching a startup like Hulu, the entertainment streaming platform that is a joint venture among NBC Universal, NewsCorp, Walt Disney, and others, is a very different exercise than merging two existing business units into a consolidation JV, as Glaxo and Pfizer did a few years ago with their consumer health businesses, Glaxo Consumer Health.

Note: While this exhibit illustrates key launch tasks, issues, and risks for business style JVs, launch and integration planning is also critical in other varieties of JVs (e.g., equity investments and asset-style JVs (i.e., JVs where shareholders partner to run/manage an asset))

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

Joint ventures exist on a spectrum between startups and M&A. Startup JVs like Hulu share many characteristics with investor-backed growth companies or new businesses being incubated within a larger company. Here, launch is about defining a new business model, building a new product or technology, establishing new processes and systems, recruiting people, building a brand and relationships, and testing the market. When a startup is a JV, there are added demands related to establishing joint governance and managing interdependencies, which are often significant, as JVs seek to leverage the functional scale of parents for lower costs. We have seen an explosion in startup JVs in the last few years – many driven by sustainability pressures and opportunities. For instance, PepsiCo formed the PLANeT Partnership, a JV with Beyond Meat to develop and market new sustainable protein-based snacks and beverages.

In contrast, consolidation JVs like Glaxo Consumer Health share many characteristics with M&A, and their launch phase is closer to post-merger integration with an added overlay of governance, shared service, and a few other issues. Consolidation ventures allow companies to reduce costs in a mature segment or to gain scale in a rapidly growing one. An example of the latter is Ocean Winds, a 50:50 JV created when French energy giant Engie and Portuguese renewables giant EDPR combined their global offshore wind businesses.

Some JVs sit somewhere between consolidations and start-ups. These hybrid joint ventures combine some complementary assets, products, or businesses – but also bring together partner capabilities to create something fundamentally new. Airbus started life as a joint venture like this, integrating the existing aircraft design and manufacturing capabilities of its three European owners to create a new global commercial aircraft business intent on challenging Boeing. A more recent example is Fluence, an energy storage JV that began as a 50:50 partnership between AES and Siemens. The partners formed the JV to build a new global energy storage business – but they also brought key assets to the venture, including AES’s technology and Siemens’s global sales force.

A JV’s archetype is not the only consideration shaping launch, of course. A venture’s overall materiality, its geographic and product scope, and whether it is a true business or a narrow operating asset will also shape the demands of launch. So too will the profile of the partners. For instance, when the partners hail from unfamiliar countries and speak different languages, understanding and managing cultural differences will take on an elevated importance. Similarly, if one partner plans to financially consolidate the venture on its books, there will likely be added finance and compliance requirements.

To the untrained eye, it is easy to see a JV launch as simply an exercise in managing activities, risks, and interdependencies across a high volume of functional workstreams. But this orientation misses the key themes that differentiate JVs from standard project management, post-merger integration, or new company start-ups. We call these differentiators the Four Strategic Imperatives of JV Launch.

These four imperatives introduce unique added twists and demands inherent to the shared ownership and control of JVs (Exhibit 2). These launch imperatives cut across JV archetypes, and strategically inform individual functional workstreams. Getting these imperatives right is essential to JV success.

Getting a JV off the ground starts with being clear and aligned on the venture’s strategy and business plan. It is common for each owner – and executives in each owner – to have their own views of the specific market opportunity and risks, and to hold different strategic interests and potential conflicts outside the JV. If these individual interests are not addressed and aligned early, conflicts will develop. Questions that need to be answered often include: What products and segments will the JV target first? Will the JV focus on gaining market share or driving profitability in the near-term, and how will this impact the approach to pricing and investments? What are the specific financial and operating targets in year one? Will the parents seek external financing or self-fund the venture at first? Will the venture subsequently fund itself out of retained earnings, or be required to send regular dividends and justify the return of capital to fund operations on an annual basis? Even subtle differences in the answers can create delays and early tensions.

Prior to closing the deal, those responsible for launch – including the launch leaders and PMO – need to work with the executive sponsors, deal teams, and future JV management to convert the high-level business case and financial model into a VC-quality business plan. This should define exactly how and where the JV will compete, describe how the JV might evolve beyond its initial scope, set financial and operating targets, plan capital expenditures, and define staffing requirements over time. This sounds basic, but the process will expose differences and gaps in parent company expectations for how the JV will compete. These disparities will need to be reconciled. Indeed, the act of reconciling differences will often unearth new sources of competitive differentiation.

Other areas that can drive strategic clarity include financing discussions and staffing plans, especially around CEO selection.[1]For additional details on strategy, business planning, and setting targets in JVs, please see: “The Joint Venture Balanced Scorecard: Next-Generation Scorekeeping for JVs,” James Bamford and … Continue reading For instance, in a four-partner JV among five banks that consolidated certain non-core operations, the selection of the CEO inadvertently drove needed alignment. After interviewing a number of external candidates, the owners offered the CEO job to an industry veteran who had worked for or alongside several of the owners. Before accepting, that candidate asked to meet with the business sponsor of each parent company – individuals who would serve on the JV’s Board. He used those meetings to understand each parent’s vision, probe their underlying interests and constraints, and test certain assumptions in the business plan and financial model. He then proposed six specific objectives that the JV would focus on during the first nine months – and made the executive sponsors’ collective endorsement of those objectives a pre-condition of accepting the job. As he later explained, “I know those guys, and if I don’t get them to agree now, I am going to spend the next 12 months trying to wrestle them into agreement, which will be painful, done without any leverage, and will almost certainly fail.”

A detailed business plan endorsed by the owners is important – but it can’t entirely insulate the business from early bumps. Consider the North American Coffee Partnership, a 50:50 JV between Starbucks and PepsiCo that sought to combine Starbucks’ coffee expertise and brand with PepsiCo’s manufacturing and distribution muscle to develop and market cold, ready-to-drink coffees to be sold at groceries, convenience stores, and other outlets. While the JV has been enormously successful, it stumbled out of the gate when its first product – a carbonated coffee – flopped in early customer trials. “We had a great partner, a leveraged organizational model, but no product,” one Starbucks executive recalled. The partners ultimately redefined the JV’s product, drawing on the lessons learned from those initial market tests, and built a multi-billion-dollar business selling bottled Frappuccinos and other ready-to-drink coffees.

The second launch imperative relates to defining the JV’s level of independence and the roles of each partner – what we call the JV Operating Model. This starts with developing principles-based answers to questions like: How independent will the JV be on Day 1, and how will this change over time? Will the partners play an equal role across the venture, or will one partner be more involved overall? Alternatively, will individual partners take a lead in a particular phase, function, geography, or product line? And is there a preference for how the partners will be involved – for instance, through the provision of support services, direct staffing, or use of their processes, systems, or technology?

Ultimately, the partners should agree to an Operating Model Framework – that is, a roadmap of the location, level, and nature of each partner’s involvement in the JV, and how these things change over time. Consider a 50:50 JV to design, build, and operate a series of plants using a new technology to convert plastic waste into a sustainable feedstock for refineries. To define the JV’s operating model, the partners first mapped the main functions and sub-functions of the JV’s business system (Exhibit 3). The main business functions, such as project development, construction and start-up, and operations and maintenance, were listed across the top, with key sub-functions and activities displayed as blocks underneath. The partners defined the main corporate support functions, such as finance, IT, legal, and human resources, at the bottom. For each element of the business system, the parties mapped the location of each partner’s involvement in the JV, as well as where the JV management team and staff would take the lead over time as the business transitioned to steady-state operations.

he partners refined and converted this high-level map into an Operating Model Framework that defined not just the location of partner involvement, but also the level and means of a partner’s involvement, including where the JV would use parent company processes, systems, tools and technology, services, and secondees. Working with the deal team, the launch team developed the first version of this Operating Model Framework three months before deal close and gained directional endorsement from the Executive Sponsors and Steering Committee. Doing so established a shared vision of the how the JV’s operating model would work in practice, and provided tangible and integrated guidance for individual functional workstreams.

These are critical issues to get right. For instance, our analysis of 39 large JVs that depended on their parents for services showed that two-thirds had serious issues with service governance and management – i.e., tensions arising from service quality and timeliness, cost allocations, divergent opinions on the extent to which JV management has the right to performance manage and potentially renegotiate services being provided by the parent, and parents using service provision as a form of shadow governance and a means to direct the JV or secure back-channel information about its operations.[2]See “The Codependency of Joint Ventures: Designing and Managing Owner-Provided Services in JVs,” Shishir Bhargava, Edgar Elliott, and James Bamford, Ankura Whitepaper, December 2021.

Similar thinking needs to be extended to the use of parent company processes, systems, and technology. In building a new joint venture, the partners will need to map out what processes and systems the JV will need and whether the venture will import them from one parent or build its own. In working through process and system design, it is essential to ensure the overall result creates a seamless whole, not a Frankenstein-like patchwork. This demands an iterative approach working across functional teams to make sure that different processes and systems fit together. For example, if Parent A plans to deploy the IT systems for manufacturing, and Parent B seeks to provide the broader IT backbone to capture scale efficiencies, there may be dissonance in getting two different corporate IT systems to work together – undermining cost savings and operating efficiencies.[3]For a discussion on corporate processes and systems in JVs, please see: “How Do Your Corporate Standards Map into Your JV?” James Bamford and Joshua Kwicinski, The Joint Venture Exchange, August … Continue reading

Joint venture legal agreements include terms that set the basic requirements for governance, including voting rights, board size, and meeting quorums. But the legal agreements often provide limited guidance on how the governance of the venture will work in practice. A central task of the launch phase is thus to establish how the governance will function on a day-to-day basis. This includes defining what type of board the partners want (e.g., a highly activist board vs. a corporate-style board) and associated role expectations for directors, the structure and composition of committees (e.g., whether to rely entirely on functional experts, not on the board vs. placing some board members on committees to promote connectivity), and the level of delegations to management.

JV governance design also includes defining how each parent company will organize internally to oversee and support the venture. For example, our analysis shows that high-performing JV governance systems utilize a clear Lead Director from each parent company who holds integrated internal accountability for the JV and is supported by a small cross-functional internal team. This internal team supports the company’s JV board of directors, coordinates the company’s requests and support for the venture, and helps manage internal approvals – which is key to reducing the “governance tax” on management and getting the JV the timely assistance it needs.[4]For additional discussion on JV governance, see: “Joint Venture Governance Index: Calibrating the Strength of Governance in Joint Ventures,” James Bamford, Shishir Bhargava, Martin Mogstad, and … Continue reading

JVs introduce a range of novel talent and organizational design challenges, including defining the rules of the road for parent secondees, building incentive plans and other elements of a compelling employee value proposition for direct employees, and creating a cohesive culture that leverages, but is not constrained by, the legacy cultures of the parents.

Let’s start with secondees. More than 50% of JVs begin life with the CEO or General Manager seconded from one of the parent companies. In many JVs, the legal agreements define multiple positions, including the CEO or CFO, as “reserved slots” to be filled by one of the parent companies. It is not uncommon for new JVs to have 20 or more parent secondees on Day 1 filling key management and technical roles. Launch planning will need to define expectations for secondees in terms of loyalty to the JV versus their nominating parent, and establish norms and protocols for any informal discussions and back-channel communications with their parent company. Parent companies often arrive with fundamentally different views on these topics.

The partners will also need to align on how secondees will be selected, reviewed, and compensated. For example, what role will JV management and the non-seconding parent play in interviewing secondee candidates, and what level of transparency will they have into a secondee’s final performance ratings and compensation? Will the JV CEO or the secondee’s supervisor in the JV be allowed to participate in parent company internal calibration discussions, and be able to represent and defend the secondee’s initial performance rating? Will secondees’ annual bonuses be directly linked to the performance of the JV, or will the group component of performance be tied only to parent company performance? In our experience, secondees can offer real benefits to a joint venture, such as providing the ability to quickly staff key positions with known strong performers, helping the JV understand parent company needs, and promoting skills transfer to and from the JV. But secondees can also introduce risks, such as undermining a fully cohesive culture and fostering mistrust. These risks should be addressed during launch by clearly defining and aligning secondee principles and policies, and communicating these across the organizations.

Most JVs will also have direct employees, whether those hired from the outside or transferred-in former parent company employees who have severed their employment relationship with the parent. How will the JV ensure it is truly able to attract and retain its own high-caliber staff? This is easier said than done. While JVs may offer great potential on many elements of an employee value proposition, they also introduce structural disadvantages. Our recent survey of JV CEOs showed that 60% believe it is harder to attract and retain talent into a JV compared to a wholly-owned business, and only 15% believe it is easier.

Launch is the time to design a talent program to reverse this reality – and use the JV’s ownership structure and relationship with the parent company to its advantage to build a distinctive employee value proposition. A compelling talent value proposition is constructed from five building blocks – great company, great team, great job, great rewards, and great development. JVs offer certain distinct advantages and disadvantages on each of these relative to wholly-owned businesses (Exhibit 4). Our engagement surveys of JV employees and secondee populations show that the “great job” element is ranked as the most important, while “great rewards” and “great team” score relatively less important.

The goal of launch is to maximize the advantages and minimize the disadvantages across all the building blocks. For instance, in a renewable energy JV, the partners looked very closely at the “great development” element and established a whole set of programs that would allow direct employees to participate in parent company training and development programs. They also established a “rebadging program” that allowed high-performing JV employees at a certain level, who had been with the company for five years, to apply to become parent company secondees. Those who were accepted then had their longer-term careers managed by the parent, opening up significant career headroom in the larger parent company.

*Average of stated and implied relative importance of building block to JV employees and secondees

Source: Ankura JV Talent Engagement Survey analysis

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

Launch is also the critical moment to establish a great culture. In many high-performing JVs, the parents use JV formation as an “event” to create a culture quite different from either parent company’s legacy operations – often to be more nimble and innovative, less bureaucratic, and lower cost. In our experience, JV launch planning should include a series of “cultural workshops” with JV management designees and select parent company staff to define answers to these questions.[5]For further discussion on key talent and organizational issues in JVs, please see: “Secondee to None: How Joint Venture Secondment Agreements are Often Deeply Flawed,” Jacob Walker, Shishir … Continue reading During launch, the parents and future leadership team need to purposefully decide on the desired culture of the JV and design structures, processes, policies, and other mechanisms to help mitigate differences between parents.

Beyond the four strategic imperatives, launching a world-class JV also depends on running the process the right way. Below we share key observations on launch planning and execution.

Launch planning is critical to expose potential misalignments that a traditional deal process may never uncover. Consider a large 50:50 Middle Eastern natural resources JV with a fairly boilerplate set of legal agreements that defined the authorized scope of the JV – each shareholder’s contributions, capital commitments, and ownership rights – and a set of standard governance, dispute, and exit provisions. What the legal agreements did not do – and what brought the venture to the brink of unwinding 18 months later – was adequately define the JV’s operating model.

Would the JV be quasi-operated by the more experienced partner, running on its processes and systems, or would it be operated as a true 50:50 JV? Would the JV be a large operating asset that depended on one partner for critical corporate support, or would it be structured as a standalone business, with its own finance, purchasing, technical support services, and sales and trading functions? The partners disagreed on the answers to these questions. Had they run launch planning in parallel with the deal discussions, these future misalignments could have been exposed early – and could have informed key terms in the deal, including the functional scope of the venture, board delegations, and use of parent company technology, services, and operating processes.

Rather than treating launch as an activity that can be pushed until after the agreements are signed, launch should be placed in a “staggered start” to the deal negotiations (Exhibit 5).

Specifically, the internal stage gate approval process that a JV will go through should include not just the deal terms and agreements (e.g., term sheet, definitive agreements) but also increasingly detailed elements of launch (e.g., business case, launch plan, Day 1 and Year 1 organizational snapshots, operating model blueprint).

The first step in the launch planning process is to agree with your partner(s) on how to run the process. We have outlined some of these key launch process design choices below (Exhibit 6).

The answer to some of these questions is likely common across all JVs. For instance, the deal team should start thinking about JV launch early – ideally prior to any non-binding MOU or term sheet, as it informs deal terms. Answers to other design questions will vary based on the context. For instance, the level and nature of information shared with the partner is highly dependent upon legal requirements and the nature of the partner (i.e., competitor vs. not).

Prior to developing detailed functional plans, partners should first develop and align on a Launch Masterplan – that is, a high-level plan, inclusive of key mile-markers, major deliverables, closing requirements, critical interdependencies and risks, and accountabilities for activities for the 3-6 months prior to close, and for the 6-18 months post-close. As part of the Masterplan exercise, the partners should build a Launch Management Platform to enable progress tracking and cross-workstream communication. The Masterplan and Management Platform help to frame and organize detailed functional plans and serve as the organizing backbone of the launch effort.

Joint venture launch planning should be run as a collaborative and iterative process, bringing together executive sponsors and cross-functional experts from each partner on a regular basis to collectively define and review key targets, major milestones, high-level workplans, and interdependencies. Interdependencies risk going unnoticed – and unmanaged – without the opportunity for functions to collectively communicate and cross-pollinate, and to build the working relationships necessary to solve for issues in parallel. For example, the selection of HR processes and systems cannot occur in a vacuum but needs to be done in parallel with finance and IT to ensure the selection and design of a human resources management (HRM) system is coordinated with finance’s choice of an enterprise resource planning (ERP) system, and the launch of the HRM system is integrated into broader IT deployment plans.

The “end” of JV launch should not be an unnoticed event that quietly takes place when the last piece of system integration occurs, when the venture’s product has switched from prototyping into mass production, or when the last of the initial wave of hires has joined the company. Rather, JV launch should be treated as a discrete phase, with different requirements and a clear end.

Increasingly, the most sophisticated companies provide an added level of scrutiny to JVs during the first 12-24 months post-close – including monthly rather than quarterly board meetings, semi-annual rather than annual corporate-level strategy and performance reviews. Some companies think about board composition differently during the first few years, for instance, having senior dealmakers and more senior operating executives serving on the JV Board to increase continuity from the deal phase. And companies might also have an added set of planning and reporting requirements, such as bi-weekly operating reports, a separate launch project plan and budget that are relaxed after the end of launch.

The last act before the launch phase is officially closed is to conduct a formal “lookback,” or post-investment appraisal, which should include a formal debrief on the launch process, and capture best practices and lessons learned – things that can be used in launching the next JV.

Download the PDF version of this article.

JV launch is not rocket science. But it does require a very different set of tools than integrating an acquisition or launching a new wholly-owned business. And that toolkit is something that very few companies have. As one executive aptly told us some time ago, “If you get this part of the mission right, the ship almost flies itself.”

The authors would like to thank Gerard Baynham, Tracy Branding Pyle, and Joshua Kwicinski for their comments on this article, and our former Water Street Partners and McKinsey & Co colleagues Ashley Snyder and David Fubini for their thoughtful contributions to earlier co-authored articles that were important inputs into the thinking in this whitepaper.

We understand that succeeding in joint ventures and partnerships requires a blend of hard facts and analysis, with an ability to align partners around a common vision and practical solutions that reflect their different interests and constraints. Our team is composed of strategy consultants, transaction attorneys, and investment bankers with significant experience on joint ventures and partnerships – reflecting the unique skillset required to design and evolve these ventures. We also bring an unrivaled database of deal terms and governance practices in joint ventures and partnerships, as well as proprietary standards, which allow us to benchmark transaction structures and existing ventures, and thus better identify and build alignment around gaps and potential solutions. Contact us to learn more about how we can help you.