Q&A with Two Independent JV Directors

Flo Lugli of Global Hotel Alliance and Jason Mann of Life and Specialty Ventures

Key insights from the Towers Watson / Ankura benchmarking of JV executive pay levels and practices

JANUARY 2011 — Determining just how to compensate the executives who run a joint venture introduces some complicated questions for JV Boards and compensation committees. For instance: When should JV CEOs be paid like business unit (BU) heads, and when should they be paid like CEOs of independent companies? What are the choices available to JV Boards in designing long-term incentives given the lack of tradeable stock or options? And given that many joint ventures are in part created to help the parent companies capture benefits outside the JV P&L (e.g., pull-through of other parent company products, learning about new markets), to what extent should such objectives be included in the performance targets and scorecards used to determine JV executive compensation?

"*" indicates required fields

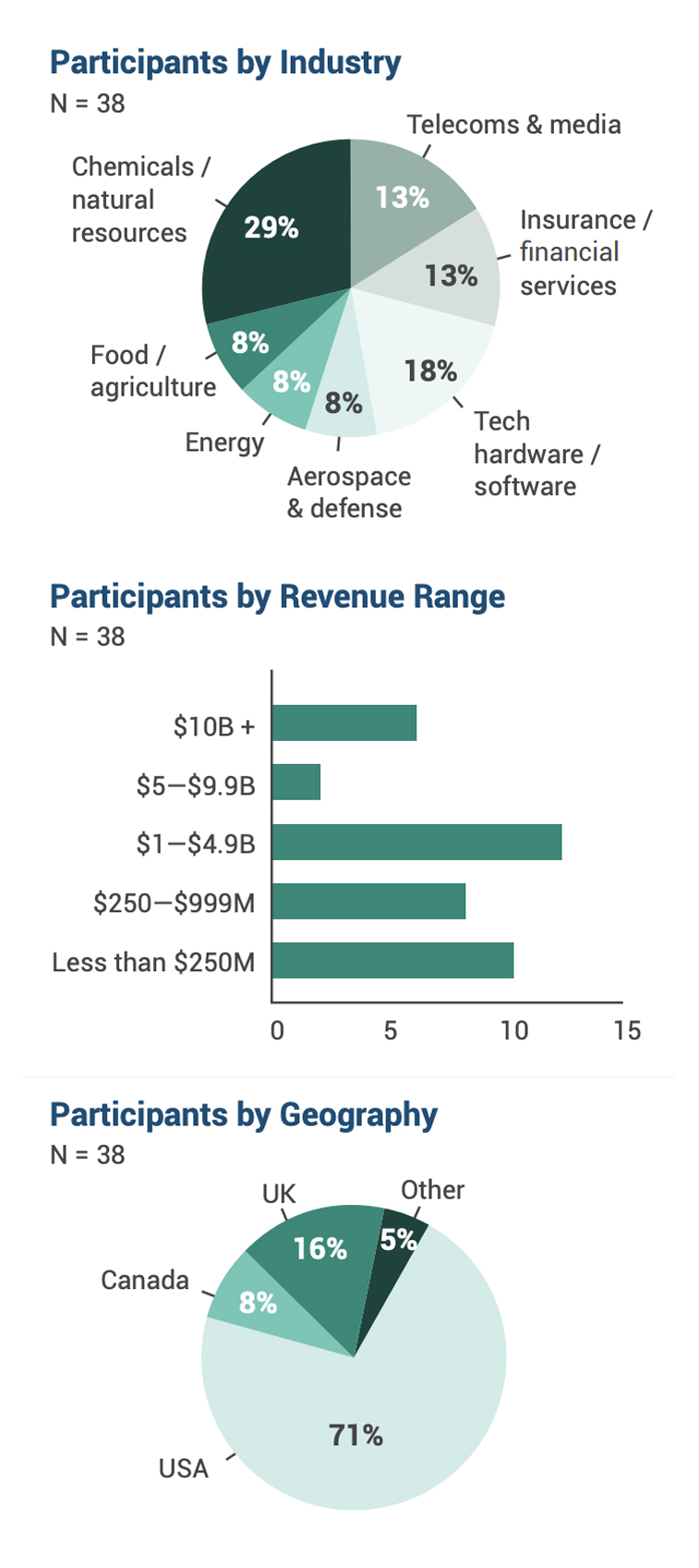

To answer these and other questions, Towers Watson and Ankura conducted the first-of-its-kind benchmarking of joint venture executive pay levels and pay practices. We looked at 38 JVs, principally in the US, Canada, and UK, and collected data on the pay levels of 160 joint venture executives. We supplemented this work through interviews and a pay-practice survey to understand company-wide compensation practices and philosophies (see Box 1: “About the Research”).

There are flaws within the compensation construct of joint ventures.

What we found is this: First, there are flaws within the compensation construct of joint ventures. JV Boards lack a sufficiently rigorous methodology to determine whether to pay JV executives in line with business unit or independent company standards – a decision that can have a 50-250% difference in total individual compensation. In fact, we found that the decision-making process of many JV Boards and compensation committees contains some natural but potentially unfair biases which can lead to venture executives being paid inappropriately (and usually too little).

This finding was counterposed by a second insight: Compensation is not the most important component in building a compelling employee value proposition in JVs. Our interviews reveal that what JV executives want most is more managerial freedom – freedom to operate the day-to-day business without tortured approval processes, palace intrigue within the parent companies, or excessive interference from operational managers within the parent companies (see Box 2: “Building a Compelling Employee Value Proposition in JVs”).

Third: While phantom equity would appear to be the “logical” answer to creating long-term incentives for top JV managers, phantom equity plans are relatively rarely used – and when they are, the results have been mixed. As a result, we see a range of new approaches being tried by the compensation committees of JV Boards to create long-term incentive plans – an area where there is still much work left to do.

The remainder of this memo outlines these findings.

Between June and December 2010, Ankura and Towers Watson conducted a joint research initiative on Joint Venture Executive Compensation. As far as we know, this was the first time that any meaningful research has been done on this topic.

Some 38 JVs participated in this research (Exhibit A). The companies came from a range of industries, and had different size and structural profiles. To conduct the research, we conducted interviews with JV executives and Board members, as well as collected data through two proprietary survey instruments. The first survey instrument captured individual executive pay-level data (e.g., actual base, annual bonus, long-term incentive compensation of members of the JV management team). The second survey was aimed at venture-wide pay practices (e.g., basis of the long-term incentive plan, role of the HR committee in compensation decisions).

Taken together, these inputs allowed us to assemble a first-of-its-kind and fact-based picture of executive compensation in JVs.

This research was further informed by Ankuras’ and Towers Watsons’ own direct client experience with JV Boards and management teams.

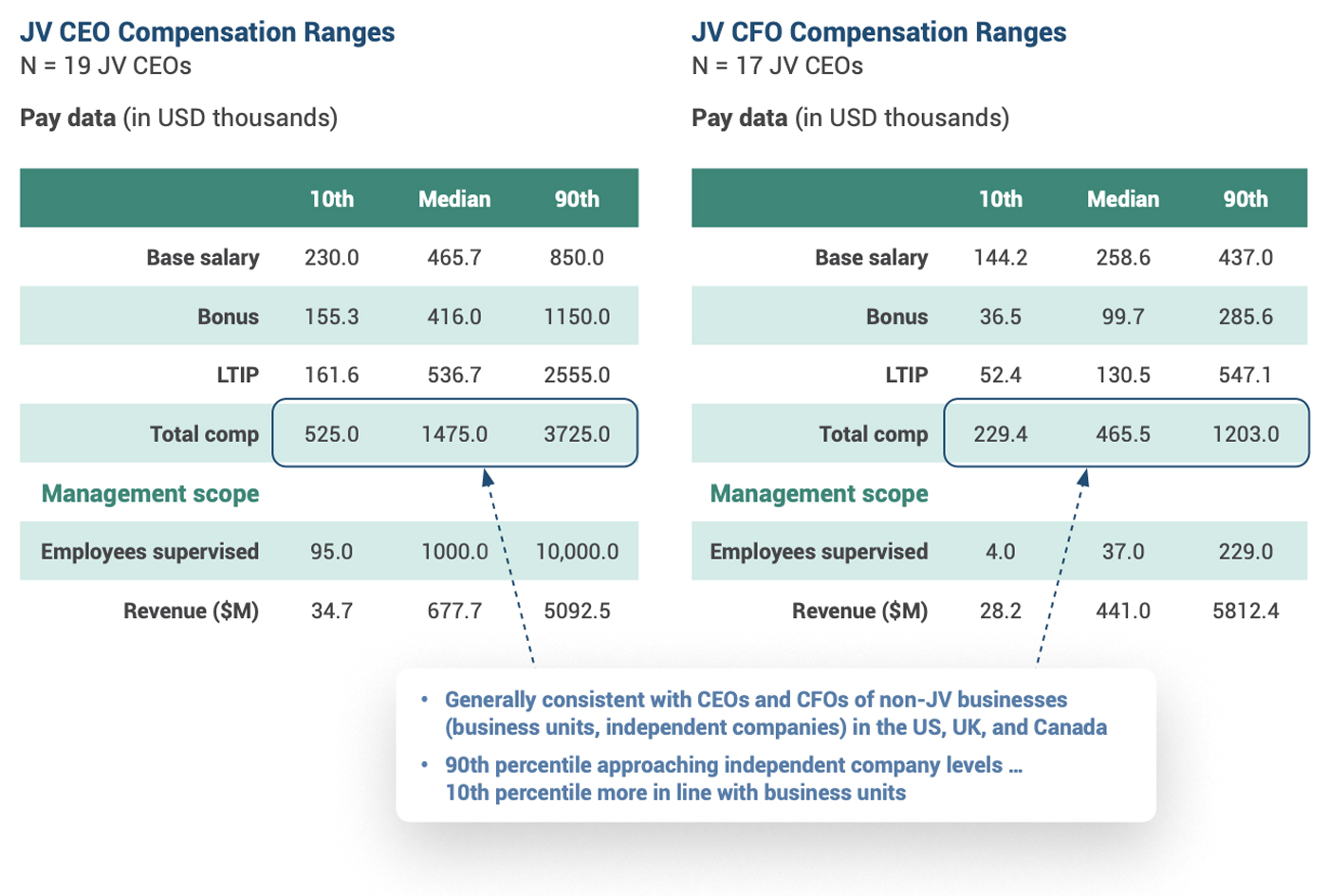

Money is not the main motivator in joint ventures, but it does matter. As part of our research, we collected pay level data for 160 executives across a range of joint ventures in the US, Canada, and the UK. A review of the raw pay level data reveals some interesting patterns.

Not surprisingly, executive compensation correlates strongly with the size of the joint venture. A phenomenon consistent with broader market trends, executives who run larger joint venture companies – as measured in terms of revenues or employees – are paid significantly more than those who run smaller JVs (Exhibit 1). In fact, JV CEOs and CFOs who are in the 90th percentile of our peer group receive total direct compensation ($3.73 million and $1.20 million, respectively) fairly close to executives running independent companies of similar size. Conversely, the JV CEOs and CFOs at the 10th percentile are compensated more like business unit executives of similar size ($525,000 and $229,000, respectively).

Source: Ankura & Towers Watson, Benchmarking of Executive Compensation, Winter 2010

NOTE: JVs in this sample set were based in the US, UK, or Canada only.

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved

We also found that executives running consolidation-style JVs have higher total direct compensation (median CEO at $1.85 million) than those running new business JVs (median CEO at $959,000). Because consolidation JVs entail a merger of existing assets or business units, these JVs tend to be much larger companies (in terms of annual revenues) than new business JVs, which are essentially start-ups combining complementary technologies and market positions of the parent companies.

Third, we found that new business JVs pay executives a lower proportion of total direct compensation in the form of long-term incentive plans (LTIP), and a greater proportion in base pay, relative to consolidation JVs. This is counterintuitive. One would expect that a new business JV would have a compensation profile similar to a start-up company, with more rewards “at risk” and tied to the future upside of the business. But what we see is the opposite. Our interviews suggest why. New business JVs tend to be seen as much riskier undertakings for potential management – and much more challenging to set meaningful performance targets. As a result, to convince an executive to leave a parent company – or to not work for a large company – new business JVs are taking some of the risk out of that by focusing on base and bonus, rather than LTIP. In contrast, consolidation JVs have a baseline of revenue and profitability – which makes LTIP a more tangible and predictable component of compensation.

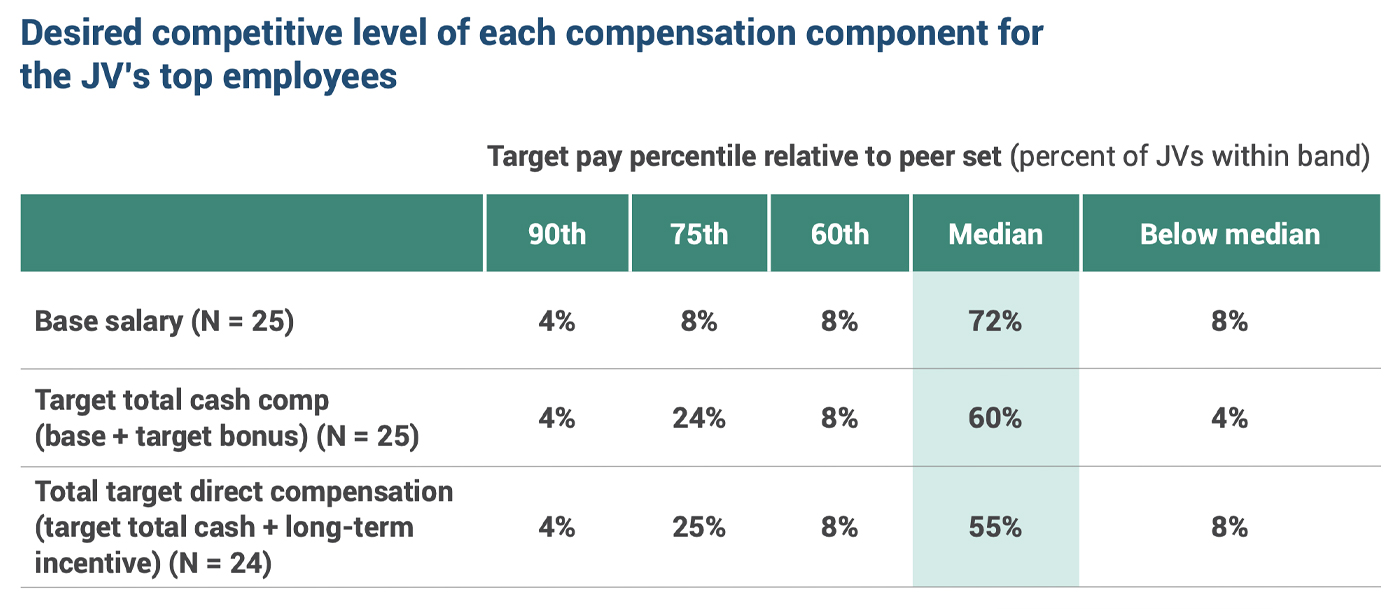

Finally, our data shows that JV Boards and compensation committees are targeting median – or above median – compensation levels within their relevant talent marketplace. Some 55% of surveyed JVs target median pay relative to peers, whereas 37% target pay levels above the median (Exhibit 2). While pay is rarely the primary driver of the employee value proposition, the data does suggest that JV Boards may appreciate certain inherent risks and managerial demands of operating a joint venture, and are targeting “good” and “better than good” compensation to attract and retain strong talent.

But here’s where the story gets interesting.

Source: Ankura & Towers Watson, Benchmarking of Executive Compensation, Winter 2010

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

JV Boards may be targeting median – or better than median – pay levels for their management teams. But what type of company is used to define the median? As it turns out, there can be a very substantial difference in the compensation levels between executives running a business unit of a publicly-traded company and those running an independent private or public company of similar size. In fact, Towers Watson research shows that executives at independent companies are paid 50-250% more than those who hold a similar role in a business unit (BU) of similar size, depending on the position. CEOs tend to skew toward the 200-250% difference, with direct reports in the middle or lower end of that range.

The simple choice of whether to treat a JV as a BU or an independent company translates into hundreds of thousands of dollars of annual compensation for a typical JV CEO or CFO.

What we see in our sample set is that JVs are distributed all over the spectrum (Exhibit 3). About one-third of the 38 JVs within the dataset are treated as “Pure BUs,” typically with compensation levels linked extremely closely to similar sized business units within the parent companies. About one-third are treated as “Near BUs” – i.e., largely compared to other business units but with a slight premium factored in and/or an inclusion of a few independent companies into the peer set that the compensation committee or Board uses to calibrate compensation. The remaining third of JVs are “Beyond BUs.” In some of these cases, the Boards define median in terms of a true mix of company types or skew toward independent private companies. In five JVs in our sample set, the business was treated like an independent public company.

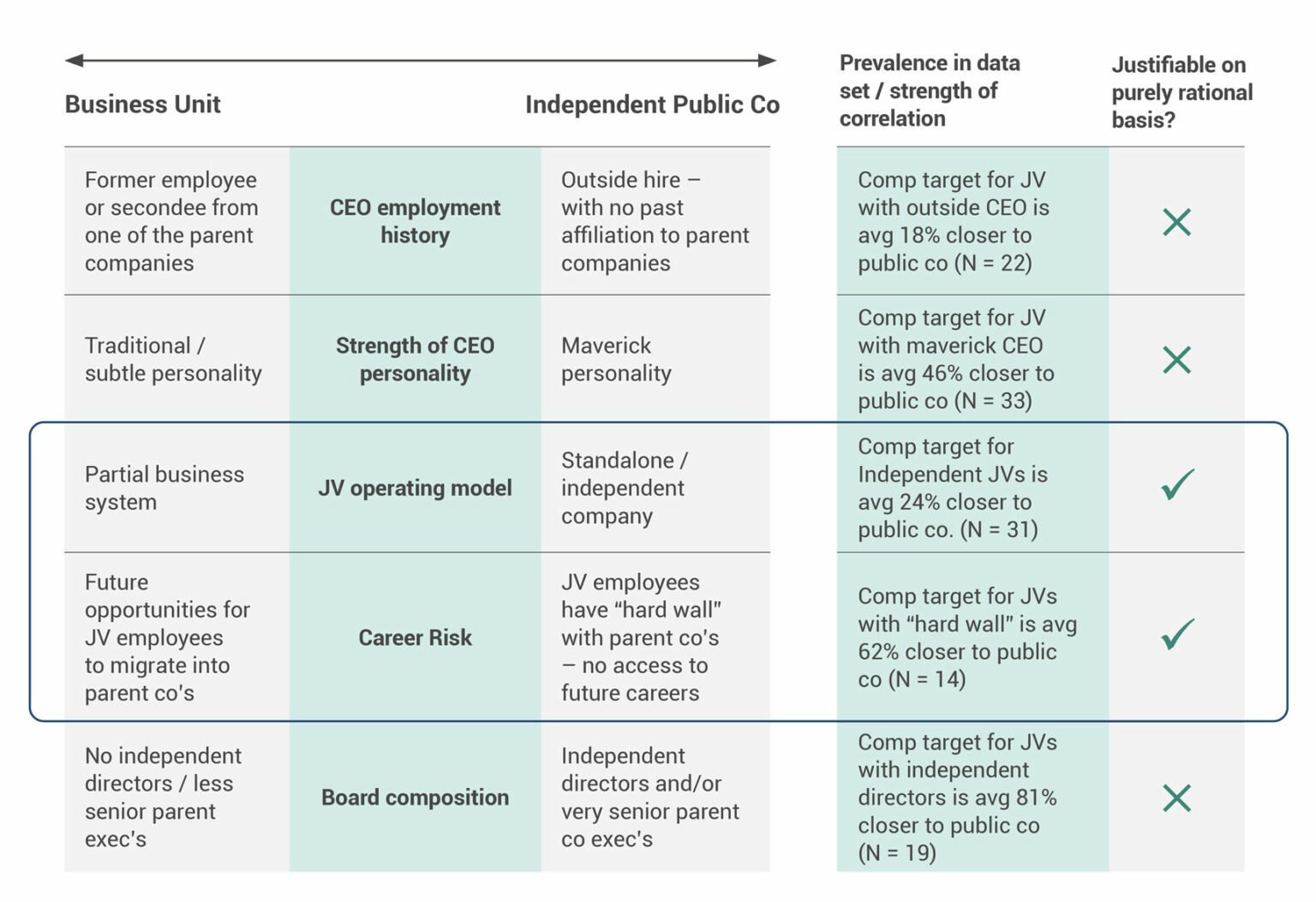

What determines where Boards and compensation committees land on this spectrum? As mentioned earlier, one factor is overall venture size: Larger JVs are much more likely to be treated as independent companies than smaller JVs. We also looked at 20 other potential factors, and found 5 with strong correlations (Exhibit 4).

While some of these factors are appropriate, others reflect natural – but potentially inappropriate – biases. For example, there is a fairly strong correlation between the JV CEO’s employment history with a parent company and the overall compensation reference point. When JVs have CEOs hired from the outside, rather than former employees from the parent companies, there is a much higher likelihood that the overall compensation construct for the JV will skew to the right of the continuum – that is, toward the higher-paid independent company model. Or look at Board composition. When a JV Board includes an independent Director – especially when that Director is the Board Chair or the chair of the compensation committee – the JV tends to pay the CEO and the rest of the management team more like independent businesses.

Source: Ankura & Towers Watson, Benchmarking of Executive Compensation, Winter 2010

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

These are natural – but potentially inappropriate – biases that influence compensation outcomes. Ideally, JV Boards would not be influenced by the contextual factors that really have nothing to do with the complexity of running the business, and therefore should not shape compensation.

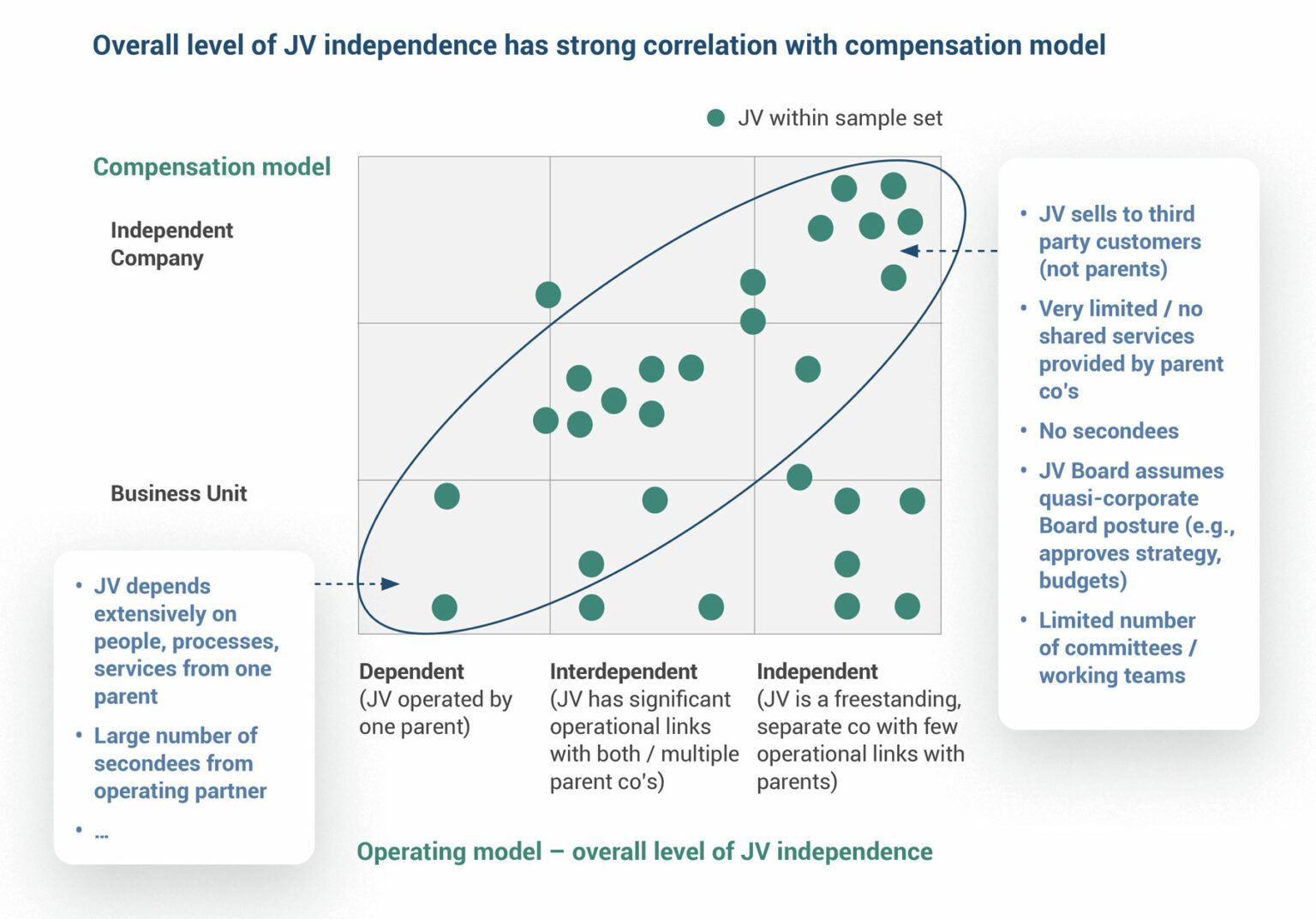

But one factor that does – and we believe should – shape the compensation construct is the nature of the JV operating model. When we plot the JV’s operating model relative to the compensation model, we see that JVs with more independent operating models tend to compensate their executives more like those running independent companies (Exhibit 5). Conversely, those JVs with less independence, i.e., they depend on one or more parent companies for shared administrative or technical services, or leverage the parent companies’ product development or sales organizations, tend to be paid more like a business unit.

Source: Ankura & Towers Watson, Benchmarking of Executive Compensation, Winter 2010

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

Operating model complexity should influence JV executive compensation. We believe that a highly independent operating model in JVs can be quite complex and similar to an independent company. But we also believe that highly-interdependent JVs can be equally challenging to manage. For example, when a JV depends extensively on its parent companies for shared services, works through the parent companies’ sales forces, and/or depends on the parents’ research or product development organizations, our experience strongly suggests that this is an inherently more complex business to run than one where all those functions sit fully inside the JV.[1]The toughest of all worlds: The JV has its own “outside” functions (e.g., raises its own debt, talks to analysts, performs its own government and regulatory affairs, has its own brand, and … Continue reading

To bring this to life, consider two different ways that Sony and Ericsson might have structured Sony Ericsson, a 50-50 JV that is today one of the largest mobile phone manufacturers in the world with $8.5 billion in sales. Option 1: create a highly independent JV where the parent companies behave like corporate investors – i.e., sit on the Board where they challenge the strategy and performance, review targets, and monitor risks, but have very limited involvement in operations. Under this structure, all operational activities – from research, design, manufacturing, distribution, marketing, and sales – are under the roof of the JV.

Option 2: create a much more interdependent business, a JV that leverages all sorts of ongoing expertise and services from the parent companies. Under this structure, Sony Ericsson might have 100 service level agreements with its parent companies for everything from technology development, manufacturing, joint sales, call center operations, and product support. The JV might share ownership of different assets with the owners, including research labs and warehouses. It would be dozens of committees and working teams, composed of hundreds of part-time parent company operational staff, to support joint product development, supply chain management, marketing, branding, sales, and service.

Now ask yourself a question: Is one of these structures more complex to manage – and thus worthy of a higher pay structure to its executives? Under the current approach of most JV compensation committees, the answer is Option 1. Option 1 would be viewed as a stand-alone business, whereas Option 2 would be viewed more like a business unit. At the same time, Option 1 would likely have 10-30% more employees than Option 2, and therefore also be viewed as a larger business, which is traditionally held in higher regard by JV compensation committees.

In other words, Option 1 would pay its executives more than Option 2, even though Option 2 may be every bit as (or even more) complex to manage.

This thinking has two important implications. First: many JV executives are today not appropriately compensated, particularly those running interdependent JVs. In fact, chances are that many are under-compensated given the inherent complexity of their businesses and natural biases in the decision-making of many JV compensation committees. Second and related: JV Boards need to rethink the traditional approach for how to determine compensation.

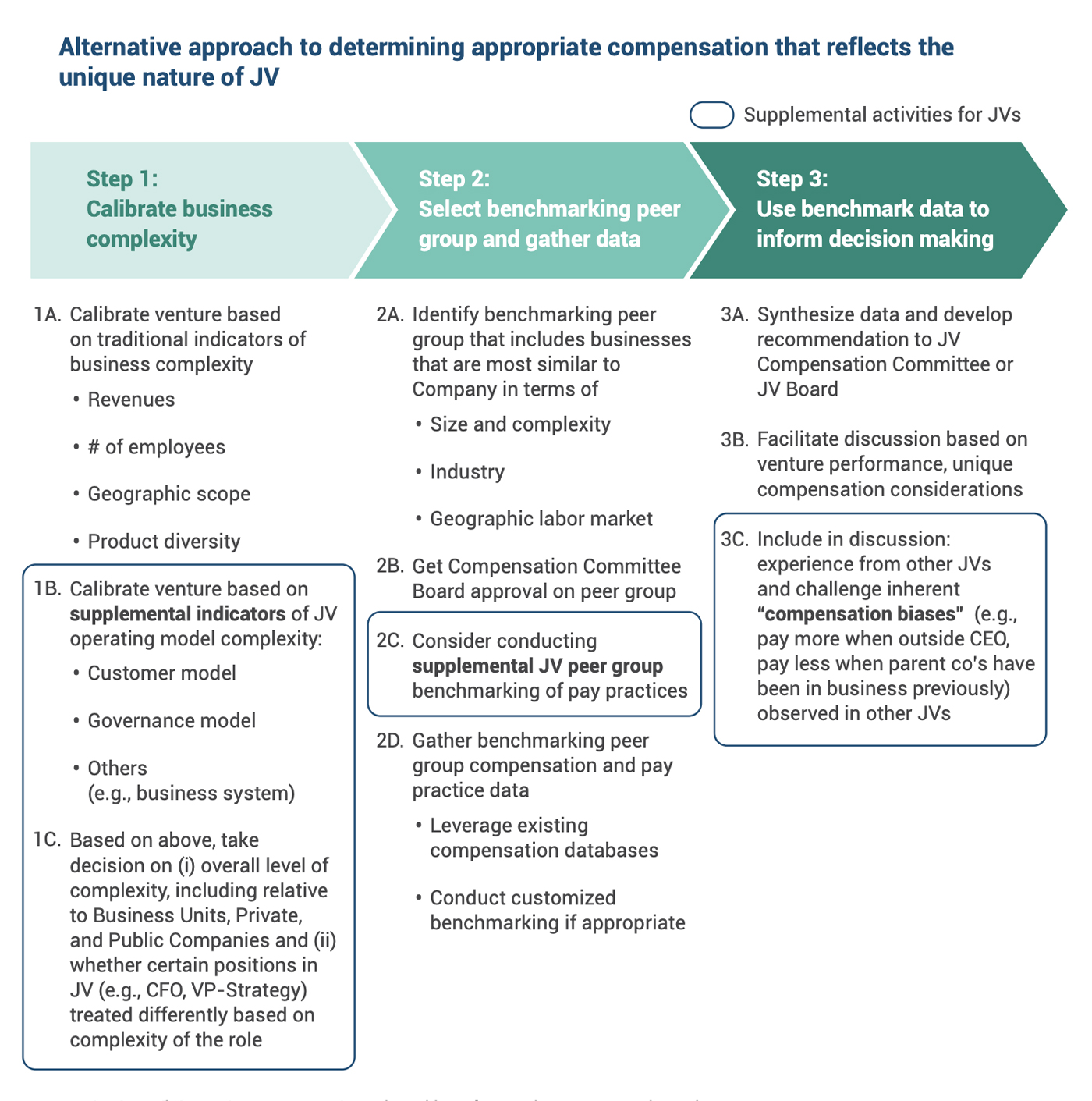

Toward a new approach. Reflecting the unique demands and dynamics of joint ventures, Ankura and Towers Watson have developed a process to assist JV Boards and compensation committees in determining fair compensation for JV executives (Exhibit 6). As shown below, Step 1 is to calibrate the complexity of the business. This would be done, initially, by using traditional metrics such as revenues, number of employees, geographic scope and product line diversity. It would then be supplemented by some indicators specific to the operating model of the joint venture.

Source: Ankura & Towers Watson, Benchmarking of Executive Compensation, Winter 2010

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

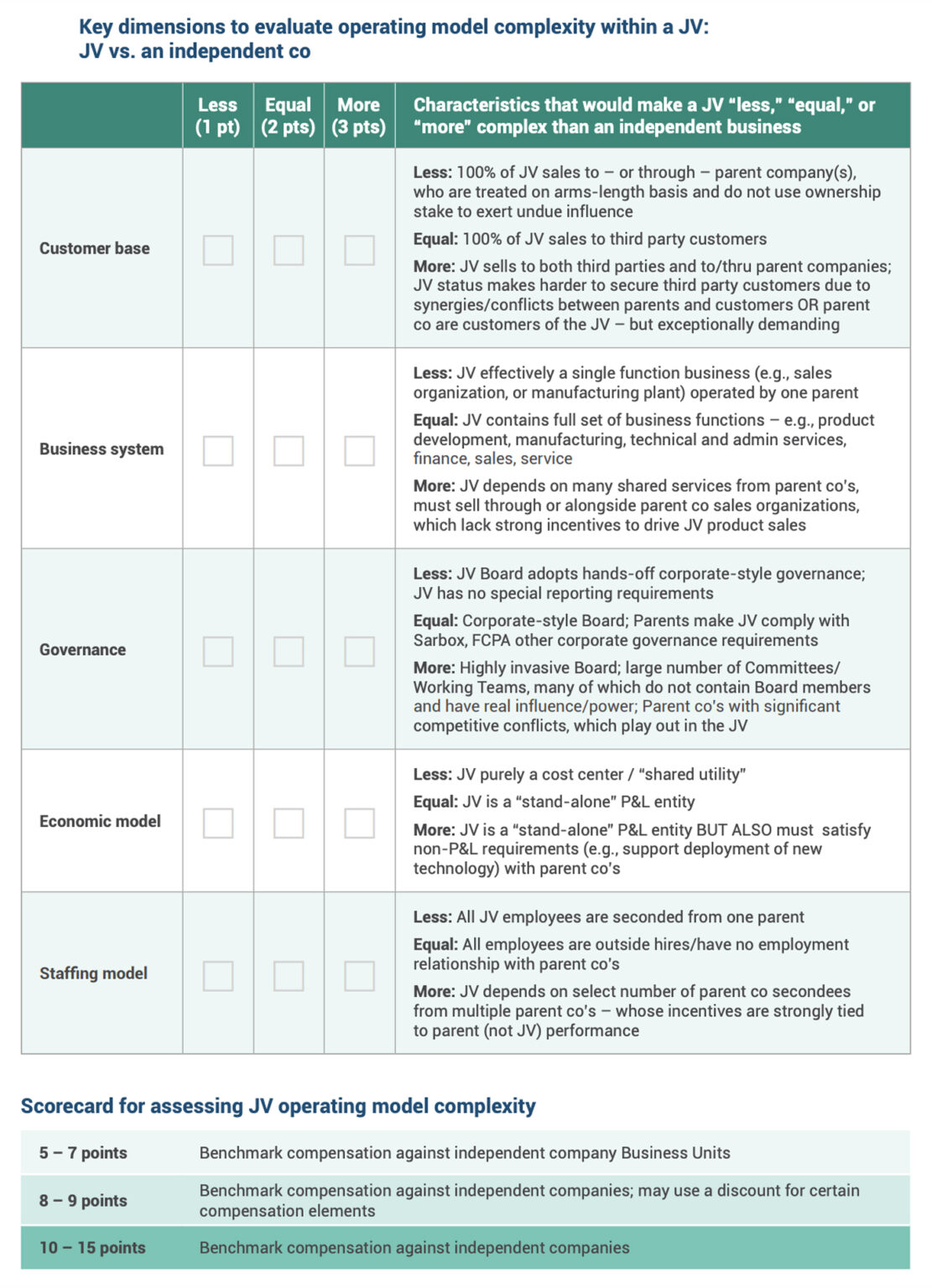

As a way to do this, JV Boards would evaluate different elements of the operating model (e.g., customer base, business system, governance, economic structure, and staffing model), and make an honest judgment as to whether the JV is more or less complex than an independent, freestanding business (Exhibit 7). Based on where the JV lands on these dimensions, the process would generate an “operating model complexity” score for the venture. This would then inform the JV Board and comp committee as to whether the appropriate peer group includes business units, independent companies, or a blend of the two.

A similar analysis can also be done at the individual executive level. For example, such an analysis might reveal that certain positions (e.g., CEO, CFO, VP-Legal, VP-Strategy) should be treated like independent company peers due to the complexity of the roles in the venture and the unique demands of the parent companies. In contrast, other positions (e.g., COO, CIO) might have a complexity level more akin to a business unit.

Step 2 is to select the actual peer group for the JV. This would play out in a traditional way (e.g., using industry competitors and other peers), with one interesting potential wrinkle. To the extent that the Board wanted a greater understanding of how similar JVs approach specific compensation practices that are unique to JVs (e.g., long-term incentives structures, secondee cost allocation and incentives, extent to which non-P&L benefits delivered to the parent companies are included in the venture’s scorecard), it could create a customized “JV Peer Group” to benchmark practices.

Step 3 would integrate this data and comparative practices to inform actual decisions on executive compensation. Again, this would unfold in a fairly traditional manner, with one potential difference. Given the evidence, we believe that the Board or compensation committee should have an explicit conversation about potential biases in its decision-making (e.g., bias to treat a very large JV or one run by an outside CEO more like an independent business), and challenge whether these may be unfairly shaping outcomes.

Source: Ankura & Towers Watson, Benchmarking of Executive Compensation, Winter 2010

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

Because few JVs have their own publicly-traded stock – and fewer have parent companies willing to give management a share of ownership – most JVs are more constrained than traditional start-ups or established public companies in creating compelling and financially-efficient long-term incentive plans. This leaves most JVs (80% of our data set) to choose cash-based long-term performance plans, with the rest experimenting with more creative approaches like phantom equity, restricted equity in multiple parents, or restricted equity in a single parent (Exhibit 8).

Performance Plans – Performance plans are typically cash-based, are generally tied to one or more financial metrics (e.g., EBIT), and pay out percentages of salary that are determined by how the JV performs against the plan’s selected metrics over a time period, typically 1-3-year performance cycles. The performance cycles usually overlap (i.e., there is a payout opportunity and new awards are granted each year).

These cash-based long-term incentive plans are relatively simple to administer, and avoid some of the risks inherent in stock- or option-based plans. Therefore, they are in wide use, particularly in newer, start-up JVs.

While this is a straightforward approach, it does have some potential shortcomings. For starters, because a cash-based plan is paid out of JV cashflows, it creates a drain on future venture earnings. Depending on the number of JV employees eligible for and the richness of the plan, this can create a sizable liability for the venture and, by extension, the parent companies. For example, in a highly-successful global technology services JV, such a financial overhang became very material, leading the JV Board to fundamentally change plan eligibility and payout levels. This has the potential to undermine an important element of the JV culture, which was built on the back of a highly-entrepreneurial and startup ethos.

A second potential shortcoming is that cash-based performance plans typically have a finite cap in the amount that can be earned (e.g., 300% of target) and do not allow for “double leverage” like a stock-based performance plan. That is, participants paid in stock can not only benefit from an above-target payout, but can also benefit from an increase in share price over the performance period.

One more shortcoming, from an employee standpoint, relates to the potential subjectivity of the targets. Because the payout is tied to Board-determined metrics, rather than more objective market indicators (e.g. share price), it increases the risk that the definition of good performance is changed, or that actual performance is highly influenced by factors outside the management team’s control (e.g., commercial transfer pricing terms on input, output, or service purchases between the JV and the parent companies).

Given these and other possible drawbacks, our research shows that a number of JVs are considering – or have chosen – more creative approaches:

Phantom Equity – A few JVs have created phantom stock option plans – i.e., established an independent valuation of the business, updated that valuation quarterly, semi-annually, or annually, and then issued phantom stock or stock options to employees tied to this valuation. While payouts are typically made

through the JV (like a cash-based plan), the advantage is that such an approach ties executive compensation to the value creation of the business. Obviously, there are various ways to structure such a phantom equity plan. In a global high-technology JV, the parent companies designed the plan so that the JV’s valuation was updated quarterly, and calculated based on the JV’s previous 12-month EBITDA multiplied by a price-to-earnings (PE) ratio of a weighted average of 12-15 comparable publicly traded companies. The phantom options vested over a four-year period, so they also served as a retention device.

By Jim Bamford and David Ernst[2]NOTE: This commentary and research on Building Compelling Employee Value Propositions in JVs is based on Ankura Partners’ own research and client work on the topic – and is not part of the joint … Continue reading

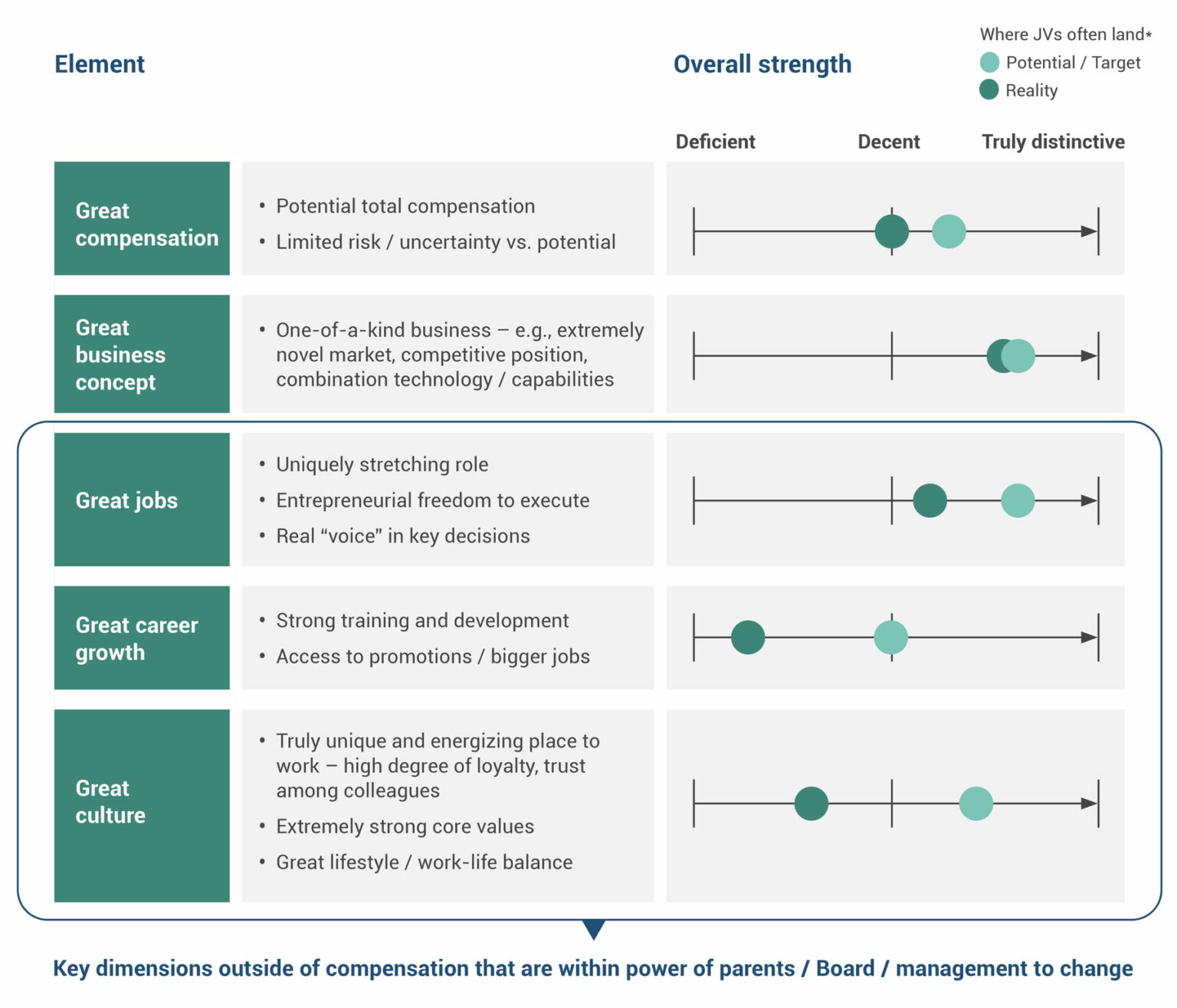

Joint ventures have the potential to create highly compelling Employee Value Propositions (EVPs), and, indeed, hold some important structural advantages in competing with other businesses in the talent marketplace. Ankura conducted an analysis of 60 JVs that breaks down the employee value propositions along five core components – compensation, business concept, nature of the job, career headroom, and company culture (Exhibit A). This analysis shows that JVs are often extremely well-positioned on an overall basis relative to other businesses, especially business units of larger companies, in attracting, retaining, and motivating top talent.

What’s interesting is that compensation is rarely the most important component. None of the JVs in the Towers Watson-Ankuras’ sample set rated compensation as the primary reason for employees to join or stay at the venture – nor the parent companies’ primary tool in attracting top talent.

Rather, where JVs have the potential to most differentiate themselves among current and future employees is in three areas: (i) the business concept, (ii) the nature of the individual jobs, and (iii) the corporate culture. This makes sense. After all, in bringing together the scale, complementary technologies, and adjacent market positions of two or more parent companies, joint ventures are often just cool, one-of-a-kind businesses.

For evidence that JVs are unique, let’s look at three joint ventures: Hulu, United Space Alliance, and Marine Well Containment. Hulu is a joint venture between NewsCorp, ABC, NBC, and Providence Equity Partners that is at the forefront of ad-supported online streaming of TV shows and movies. United Space Alliance is a multi-billion dollar JV between Lockheed Martin and Boeing that runs all flight operations for the US Space Shuttle. And Marine Well Containment is a $1 billion joint venture that ExxonMobil, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, and Shell recently set up in response to the BP oil spill, with the mission to create a rapid-response system to capture and contain oil spills from deep-water rigs in the event of an accident.

Joint ventures are not just one-of-a-kind businesses – they tend to offer managers compelling roles. We’ve found that JVs have the potential to offer uniquely stretching roles, higher levels of entrepreneurial freedom to execute, and a real “voice” in key decisions that executives in the business unit of a larger company would rarely find. In companies like BP and General Motors, being the CEO of a joint venture is one of just a few jobs in a company of 100,000-plus employees where an executive can be responsible for running an end-to-end business and managing a Board.

More broadly, members of JV management teams are often put in charge of assets, teams, budgets, and activities of a size that would be highly unusual inside a parent company. For example, in a metals and mining JV, the COO and Project Director were asked to oversee the construction and operations of a $15 billion asset – something that would not have been possible for another 5-10 years if they had remained inside their parent companies.

Similar stories can be told about joint venture culture. Freed from big company requirements and institutional norms, joint ventures can be very special places to work. For example, when Shell and Amoco consolidated certain mature North America assets into the Altura joint venture, the parent companies and venture management had the chance to fundamentally rethink how the organization functioned and felt. The idea was to create a highly independent venture with a small-company feel. The culture of Altura included an intense focus on low-cost operations, much greater individual freedoms to line managers, and a re-balanced risk/reward profile where employees would receive lower base pay in exchange for higher upside if performance targets were met. As one former employee told us: “Altura was a really special place – people were very excited to be there, excited to have all these added skills and scale to exploit these assets, and excited to create something separate from the parents.”[3]See, “Succeeding in Cross-Cultural JVs,” The Joint Venture Exchange, October 2010.

When the potential on each component – great compensation, great business concept, great jobs, great career headroom, and great culture – is tallied up, joint ventures often have the makings of a compelling employee value proposition.

Unfortunately, many joint ventures under-deliver on different components of the employee value proposition. In so doing, JVs often wind up with below average EVPs, despite the potential to be well above the median.

Our analysis of 60 JVs shows that the largest gaps are not in compensation but, rather, in managerial freedoms, an important aspect of the great job component. Talk to a JV CEO and other members of the management team and what these executives want most is not more pay (good news for compensation committees) but the freedom to run the business. This does not mean the authority to write $10 million checks without Board approval or to expand the JV into geographic or product markets outside its core business. Rather, what JV CEOs and other managers want are day-to-day freedoms – the freedom to make product decisions without excessive interference or approvals from operational staff in the parent companies; the freedom to deal with parent companies as arms-length third parties when negotiating shared service agreements; the freedom to not have to prepare for and attend 15-30 Board and Committee meetings per year; and the freedom to enter into research or marketing partnerships without undue vetting and comment by the parent company managers who do not sit on the Board.

This is an important message for JV Boards and compensation committees. While there is certainly room for improvement in the area of compensation, compensation is not the most important lever in attracting and retaining talent into JVs. The best JV Boards should start with a broader discussion about the JV’s relative value proposition to employees – and what the JV needs to do to effectively compete in the war for talent.

* Based on qualitative analysis of 60+ JVs from Ankura interviews and client work, 2008-2010

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

Parent Company Restricted Stock, Stock Units or Options – An alternate approach is to issue employees restricted stock, stock units, or stock options in the parent companies. While the value of this is not directly tied to the value of the JV, it has the benefit of not being funded out of JV cashflows (and, if desired, maintains a strong ongoing connection to the parent companies).

This proved to be an attractive approach for a large consolidation JV in the energy sector. Because the JV consolidated large business units of the two parent companies, the JV was initially 100% comprised of legacy employees from the two parents. The interim Board and management team felt it was important to keep some ties to the parents as a retention tool during the integration period. The plan was designed around a cash grant that was divided in half, with 50% “invested” in hypothetical shares of stock in Parent A and 50% in hypothetical shares of Parent B. The notional value of those shares was tracked over a three-year period – exposing JV employees to the share price fluctuation of each parent. All shares were “sold” at the end of the three years. Participants then received 0-200% of the new value of this dollar grant, depending on the JV’s return on investment relative to an industry peer group, paid in cash via deferred compensation. Now that retention and parent company loyalty are less of an issue, the JV is able to focus on driving internal behavior towards increasing the long-term value of the JV. Its revised LTIP is no longer tied to parent company stock, and instead pays a simple cash grant tied to the JV’s performance against a set of defined internal metrics like project execution and portfolio management.

A related approach is to issue restricted stock, stock units or stock options in just one of the parent companies. We have seen this in a number of cross-border JVs, where one parent company is state-owned (and thus has no public stock) or where the JV is operated by or otherwise strongly tied to one parent company due to geography or other factors.

Consider the case of a high-tech JV tied closely to one parent. The JV uses the HR policies and procedures of that parent almost 100% of the time, including payroll support – so the parent sees the details of every compensation choice. The closeness leads the parent to treat the JV as a business unit – and ultimately results in a soft requirement that all compensation choices correspond to parent policies. As a result, the JV LTIP is simply an extension of the parent LTIP to cover JV employees, who now receive three-year cliff vesting restricted stock units in the parent company that are distributed according to parent company grade and pay eligibility requirements.

Ultimately, there is no “one size fits all” approach to building a compelling joint venture LTIP. We believe that JVs need to consider a range of factors related to their business situation and human capital goals to arrive at what works best for them, and the clear solution for one JV may not work for another. The best answer may lie in one of the programs we outlined, a combination of ideas, or an imaginative new approach yet to be tried by a JV. Regardless of the solution, we feel strongly that JVs should be open to considering creative alternatives beyond the traditional cashbased plan, in keeping with the entrepreneurial spirit driving many JVs.

~~~

Joint ventures are becoming an ever-more important asset class in many companies’ portfolios. Isn’t it time to design the process for determining compensation in a way that reflects the unique realities of JVs – rather than imposing processes designed for independent companies or business units? We think so.

We understand that succeeding in joint ventures and partnerships requires a blend of hard facts and analysis, with an ability to align partners around a common vision and practical solutions that reflect their different interests and constraints. Our team is composed of strategy consultants, transaction attorneys, and investment bankers with significant experience on joint ventures and partnerships – reflecting the unique skillset required to design and evolve these ventures. We also bring an unrivaled database of deal terms and governance practices in joint ventures and partnerships, as well as proprietary standards, which allow us to benchmark transaction structures and existing ventures, and thus better identify and build alignment around gaps and potential solutions. Contact us to learn more about how we can help you.