JULY 2015 — It is certainly possible to negotiate a Joint Venture Agreement without dwelling intensely on the future. Indeed, dealmakers have some very good reasons not to over-prescribe the future. After all, defining the future takes time, draws attention away from getting the deal done, and adds to non-closure risk. Defining the future can also introduce potential liabilities and limit future flexibility, as it may lock the company into commitments that do not make sense down the road.

Enter your information to view the rest of this post.

"*" indicates required fields

One dealmaker summed it up this way: I’m a dealmaker, not a soothsayer. It is dangerous to predict the future – and far wiser to let our executives overseeing the business address events and issues as they arise.

But the low success rates of joint ventures – and high level of post-close misalignment and exit issues – suggest that failing to think about the future may not always be the best way to approach joint venture dealmaking. Consider a few examples where incomplete thinking about the future caused severe and avoidable pain:

- A U.S. industrial company entered into a 50:50 JV that consolidated a mature business line with that of a competitor. The exit clause in this deal was structured around a common buy-sell provision, whereby after three years, either party had the right to trigger exit by offering a price at which the non-initiating party could either buy or sell. This seemingly fair exit pricing methodology disadvantaged the U.S. company because it was the “natural seller” of the business. This meant that the counterparty knew that it could offer 10 to 15% below fair market value (FMV) for the business, with little to no fear that the US company would choose to be the buyer. That deal term cost the US company between $120 and $180 million.

- A Middle Eastern conglomerate formed a 50:50 JV with a global company to develop and operate a metals processing venture, which included a $10 billion refinery and related infrastructure. The legal agreements were well-written, and included traditional language with regard to joint governance and control. Additionally, the partners entered into mirrored versions of master services and secondment agreements with the venture. Two years into the venture, however, it became obvious that the partners held fundamentally different views of how the JV should be operated vis-à-vis the shareholders. The global partner saw itself as the Lead Operating Partner – that is, the provider of the technology, systems, and practices on which to build and operate the venture, and viewed the venture as an asset within its portfolio that should depend on it for marketing, sales, and other functions. In contrast, the local conglomerate saw the JV as an independent business, which would have its own processes, systems, and brand – and would ultimately build its own marketing capabilities. These fundamental differences in the venture’s operating model caused significant deterioration in trust and management turnover – which then led to delays in investment decisions that cost the shareholders at least $500 million in profits.

- A global publishing house entered a joint venture in Asia, seeking to grow in a key emerging market by partnering with an established local player. After three years, the business was not meeting targets, and opportunities were slipping away as competitors gained market share. Yet the JV Agreement prevented either partner from unilaterally replacing the CEO or forcing needed investments. Meanwhile, the exit clause prevented the global publisher from competing in the local market for three years once it exited the JV, so selling was not an option. Ultimately, the negotiated exit agreement was expensive and delayed.

The low success rate of JVs suggests that failing to think about the future may not always be the best approach to joint venture dealmaking

We believe that companies need to expand the set of questions they ask during the deal process – and look out across the full venture lifecycle for more clues about what issues the parties will predictably confront in the JV. Dealmakers should address these issues pre-close, while they have all of the leverage, and none of the risks. Specifically, front-loading the future means having good answers to a number of questions, including:

- Does our likely future position disadvantage us relative to the counterparty if we adopt seemingly fair, boilerplate deal terms (e.g., on exit pricing, dividends, future investments, etc.)?[1]By “boilerplate,” we mean contractual arrangements that are fairly standard in Joint Venture Agreements, and are therefore viewed as the default option by dealmakers. Though boilerplate deal … Continue reading

- Have we defined the venture’s strategy, governance, and operating model at sufficient detail to expose any serious future misalignments with the counterparty about how to run the business?

- Does the proposed deal inappropriately lock us into a partnership from which it will be extremely painful to escape in the future (e.g., should the venture not perform well, or should our strategy change)?

- Have we adequately anticipated the natural evolution or inflection points of the venture (e.g., the shift from research to commercialization, or from the project/ design phase to the build/ operate phase), and driven this into the deal terms?

The purpose of this note is to tackle the first question.[2]Other Ankura articles, webinars, and roundtables have addressed or will address the other three questions. For example, on 25 June 2015, Ankura hosted a webinar, “Defining the Governance Model for … Continue reading

Companies need to expand the set of questions they ask during the deal process, including whether the company is disadvantaged by seemingly fair, boilerplate deal terms

BREAKING FROM THE BOILERPLATE

Many dealmakers rely on standard terms or model-form agreements to expedite the dealmaking process, and limit the areas of negotiation. But in certain situations, such terms can be highly problematic for one of the partners if certain events occur – events that can be predicted during dealmaking. Therefore, a key element of front-loading the future is looking at these boilerplate terms, and testing whether standard language that seems eminently balanced and fair will actually disadvantage your company down the road. If the answer is yes, then dealmakers need to deviate from the traditional, timeworn path of the boilerplate, either by opting out of standard contractual language, deepening existing language, or developing additional agreements pre-close.

Boilerplate terms expedite the dealmaking process, but can be highly problematic for one of the partners if certain events occur – events that can be predicted during dealmaking

To illustrate this work, consider three deal terms, and how a deeper view of the future drives the company away from the boilerplate:

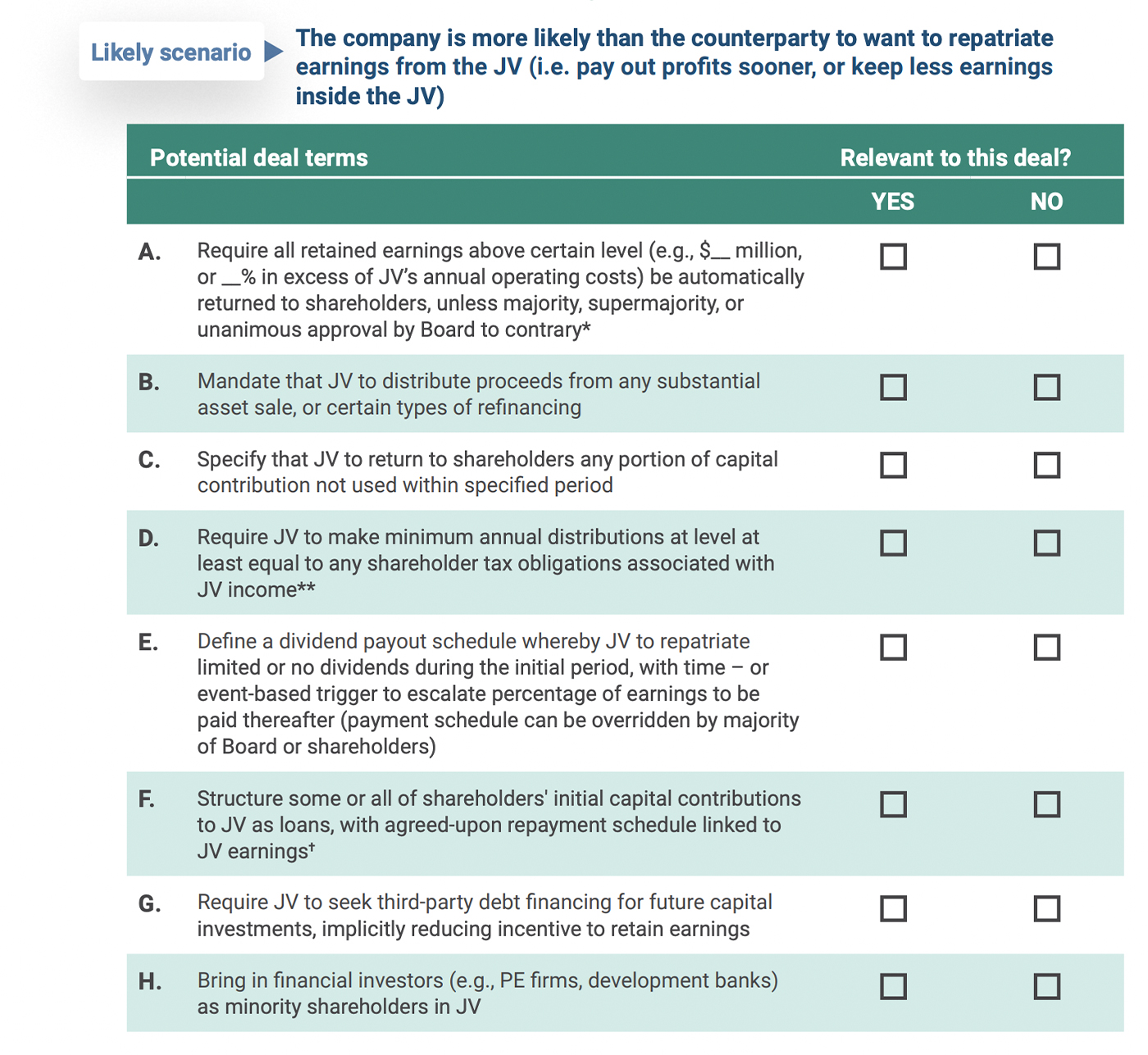

Dividend policies

The typical JVA requires a supermajority vote of the JV’s Board of Directors (or equivalent) to approve any financial distribution to the shareholders. While this standard term may seem reasonable, it can disadvantage a shareholder in certain situations. For instance, if your company is entering into a 50:50 JV with an eye toward generating near-term financial returns, but the other shareholder is more interested in growth, building market share, or keeping profits within the venture for tax or other reasons, then this standard deal term is bad for you, as it creates a barrier to getting cash out of the business. Simply put: If the partner does not want to make a distribution, venture profits have nowhere to go but to sit in the JV.

Such a standard term can also materially reduce the overall level of capital discipline across a company’s portfolio. Consider a European chemical company, which owned more than ten JVs accounting for some 30% of its total capital spending. A meaningful portion of this capital spending was self-funded by the JVs. “Effectively what this means,” according to the company’s Finance Director, “is that our earnings from these ventures are not ‘re-competing’ for capital with our other businesses and projects, and therefore, our money may not be going to the best investments.”

Requiring supermajority approval of the Board to repatriate JV earnings to the shareholders can create a barrier to getting cash out of the business

If your company sees the future unfolding like this, you should consider deviating from the standard JVA voting provisions for dividend policies. As with a number of other standard boilerplate terms, we have developed a checklist of non-standard deal terms to consider, the relevance and feasibility of which will vary by the situation (Exhibit 1). For instance, in the situation described, the company might have proposed that the agreements be structured to provide an automatic payout of any earnings above a certain level (e.g., $10 million, or 20% of the JV’s annual operating costs), unless the Board agrees by unanimous vote to the contrary. Alternatively, you might structure some or all of the shareholders’ initial capital contributions to the JV in the form of a loan, with a pre-agreed repayment schedule linked to JV earnings (and where earnings are automatically used to repay lenders prior to making other capital investments in the venture).

Exhibit 1: Dividend Policies – Beyond the Boilerplate

* A variant on this term is to establish automatic declaration of special dividends associated with other triggers

(e.g., JV balance sheet above $__ million, and no reinvestment opportunities that meet IRR of __%).

** Most relevant to LLCs, Partnerships, and other ventures structured as pass-through entities.

† Consider potential tax implications of this structure.

Source: Ankura

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

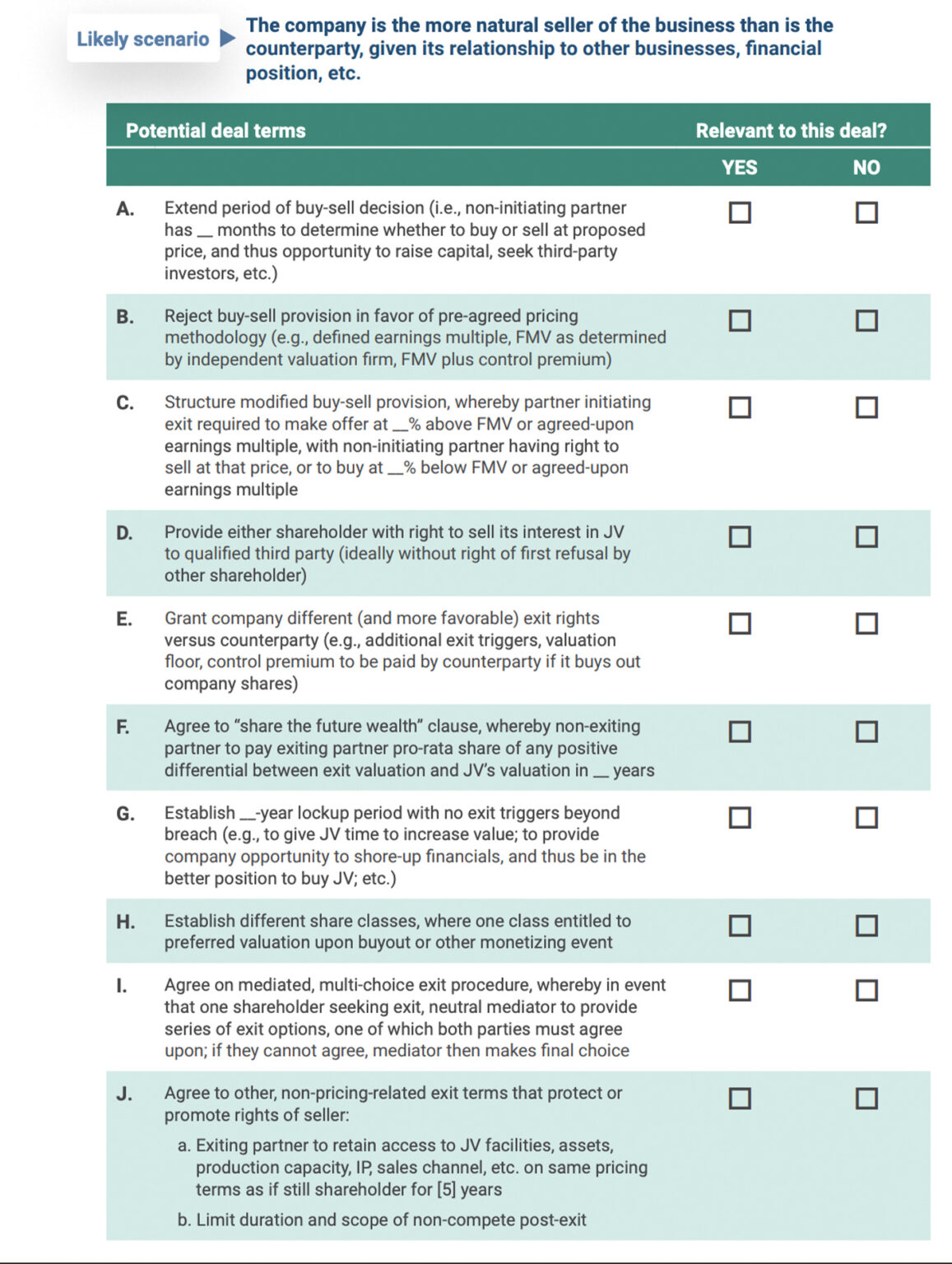

Exit process and pricing

In 50:50 JVs, it is common for the parties to agree to a buy-sell provision as a way to avoid prolonged deadlock, and prevent either party from being stuck in a business that is underperforming, or that no longer fits with its strategy. While there are different types of buy-sell provisions, the basic idea is that either party has the right to initiate a bidding process that will lead to a buyout, but does not know whether it will be the buyer or the seller of the venture. The industrial JV discussed above used a common buy-sell provision often referred to as Russian Roulette.[3]Other common forms of buy-sell provisions in JVs include a Texas Shootout and the Dutch Auction (also known as a Mexican Shootout). Under the Texas Shootout, each partner submits a sealed bid … Continue reading Under this structure, either party has the right to trigger exit, with the initiating party offering a valuation at which the non-initiating party is then given the choice to either buy or sell.

On the surface, this pricing methodology seems fair, since the initiating party sets the valuation, but does not know whether it will be the buyer or the seller at that price. However, deeper thinking about the future could lead the company to see that this is a suboptimal structure. Specifically, if your company is the more natural seller of the venture (e.g., because it views the venture as a non-core business, because it is less strong financially than the counterparty, or because the venture has far greater operational integration with the counterparty), then a buy-sell provision disadvantages your company, since the counterparty knows it can offer below fair market value for the venture.

Russian Roulette disadvantages the natural seller, because the counterparty knows it can offer below fair market value for the venture

In such cases, you should consider different ways to deviate from standard buysell contractual terms (Exhibit 2). For example, you might propose extending the period within which the non-initiating partner has the right to decide whether to buy or sell (e.g., structure as a 12-month window rather than the more typical 1 to 3 months), thereby creating greater opportunity for the company to raise capital, seek third-party investors, etc. Alternatively, you might reject a standard buy-sell provision in favor of one linked to a pre-agreed pricing methodology. For example, the JV Agreement may allow either party to initiate exit, but require that the offer price must be at or above a specific earnings multiple, or fair market value as determined by an independent valuation firm. In a financial services joint venture we recently worked on, the natural seller successfully negotiated for a provision that went even further, requiring the partner initiating exit to make an offer at 20% above FMV, while the non-initiating partner had the right to sell at that price, or to buy at 20% below FMV.

Future capital investments

JV Agreements generally do not place mandatory obligations on the shareholders to make additional capital contributions to the venture (beyond the initial capital contributions). Rather, Joint Venture Agreements typically treat future funding as a matter reserved for the shareholder companies, requiring each shareholder to independently decide whether to make such a capital investment, and only proceeding if all the shareholders agree to make such investments.

On the surface, this standard contractual term is reasonable, as one shareholder should not have the power to force the other to commit its capital. But there are plenty of circumstances where this structure might disadvantage one company – and its dealmakers would be wise to test alternatives. For example, your company might find itself in a situation where the counterparty’s strategy or balance sheet makes it unable or unwilling to make certain future capital investments – for instance, expanding the facility or investing in a new product or production line – that are reasonable, and that your company wants to make through the JV.

If your company is more likely than the partner to want to make capital investments, then treating future JV funding as a matter reserved for the shareholder companies can disadvantage you

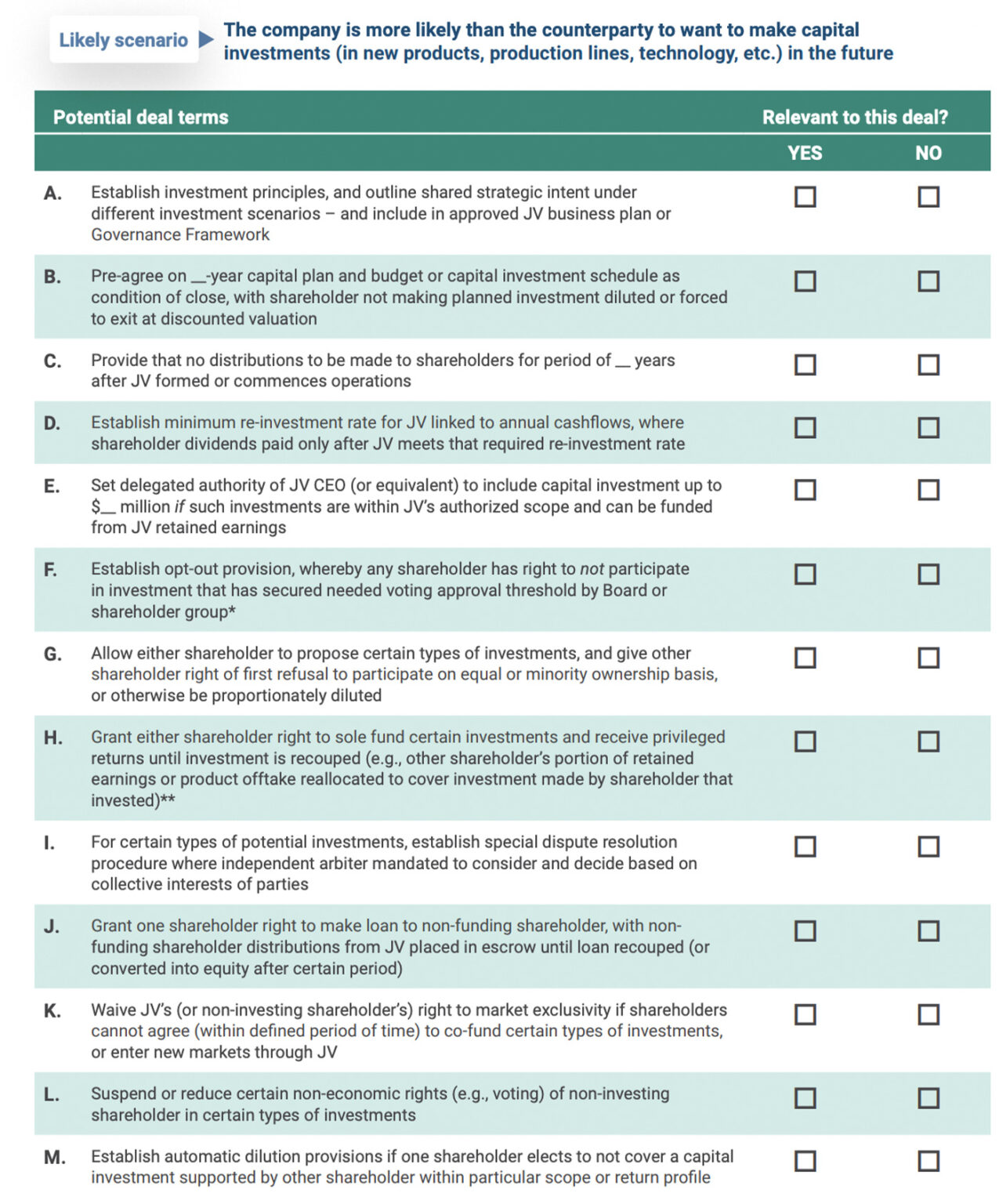

If your company is more likely than your partner to want to make capital investments, you should look at a range of less standard deal terms (Exhibit 3). For example, you might seek to define investment criteria or similar principles, and embed these within the JV business plan (agreed-upon pre-close), or within a Governance Framework document (approved as a Day 1 Board resolution) [4]A Governance Framework is a document that captures shareholder alignment on how the venture will operate – including dimensions that do not logically belong in a JV Agreement.. Going further, you might have the parties pre-agree to a three-year capital plan and budget that commits shareholders to specific capital investments. Or you might suggest funding an escrow account at deal close, where the funds are returned after a certain number of years, assuming shareholders vote not to make an investment. Or you might seek to establish a minimum re-investment rate linked to the JV’s annual cashflows, where shareholder payouts can only be made after the venture meets its re-investment target.

Exhibit 3: Future Capex – Beyond the Boilerplate

* Such provisions are more common in JVs with three or more shareholders; in upstream oil and gas JOAs, this term is referred to as a non-consent provision.

** This term could be structured to apply only to separable businesses (i.e., those with distinct assets and revenue streams). This term typically includes provisions whereby the investing shareholder indemnifies the non-investing shareholder to any consequences caused by these investments and associated activities. In the upstream oil and gas industry, this term is known as sole-risk provision, and is widely used in JOAs.

Source: Ankura

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved

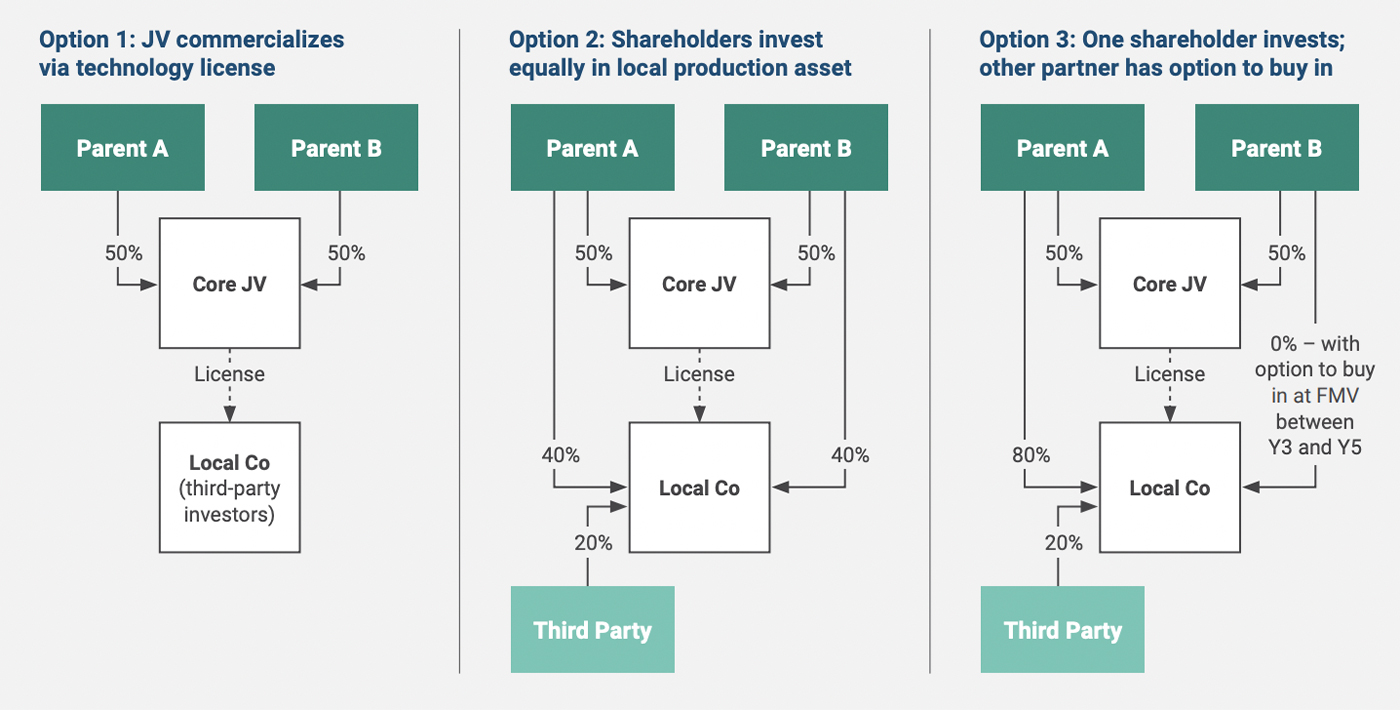

Alternatively, you could pursue creative deal structures where one company gains the freedom to pursue new investments alone if the other shareholder declines to fund the investment.

An interesting structure can be seen in a 50:50 biofuels JV to develop and commercialize a new technology (Exhibit 4). The deal was structured to enable potential future investments to be funded by only one shareholder, provided certain conditions were met. Specifically, the JV Agreement gave each shareholder the right to propose investments to commercialize the JV’s technology, products, or derivative products, which were to be approved by the JV Board. The shareholders agreed to a set of investment principles that stated that the preferred option was for the shareholders to each invest 50% of needed capital in new projects. But the agreements also allowed that if either shareholder wished to fund at a lower percentage, that shareholder had the right to subscribe to between 20% and 49% of the new investment, with a corresponding ownership percentage in a new entity created. If within three months after one shareholder had proposed such a project, the JV Board had not approved the proposal or some modification, then the initiating shareholder had the right to propose directly to the other shareholder to create a new entity to pursue the investment, or to pursue the investment on its own.

Overview of Structure

- 50:50 JV to develop and globally commercialize new biofuels technology

- Core JV to conduct research and development, and valuate licensing opportunities/direct investments to commercialize technology

- Shareholder preference for local production, or new investments to be by third parties (with JV generating income through licenses through the core JV, funded equally by the shareholders)

- Opt-in structure established to enable shareholders to invest alone (or with third-party local investor), provided certain conditions met

Additionally, the agreement stated that if a new entity was established, no third party could invest in that entity. And if the non-initiating shareholder invested at less than 50%, then no earlier than Year 3 and no later than Year 5, that shareholder had the right to increase its interest to up to 50% by purchasing equity interest at FMV.

~~~

Of course, front-loading the future involves more than just thinking beyond the boilerplate. But anticipating the future – and breaking from boilerplate contract language when needed – is one way to ensure better, longer-lasting, and fairer JV deals.

Download the PDF version of this article.