January 2017 — THERE ARE THOUSANDS of joint ventures with significant profitability, strong management, and large asset bases. Many of these could comfortably exceed the initial minimum listing requirements of various stock exchanges. For instance, the NASDAQ Global Market tier has initial minimum listing requirements (using its total assets standard) of total assets worth $75M, total revenue in the last fiscal year – or in two of the last three fiscal years – of $75M, and $20M in market value of publicly held shares. As balance sheets get squeezed, as JVs mature, and as global companies seek creative ways to respond to nationalization trends (for example, through a local listing), JV shareholders are beginning to think about the IPO option for their JVs.

IPOs of JVs can be a phenomenal way to unlock value for owners – both as a means to monetize earlier investments and, potentially more important, to drive improved performance in the future through a more independent, market-oriented, and less complex operating structure. Moreover, by creating publicly-traded stock, an IPO can also create a “currency” to attract and retain top talent – something that has proven quite difficult in traditional joint venture environments. Among the many prominent IPOs of JVs in the last 20 years are VISA, Airbus, Orbitz, Amundi, and Change Healthcare (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: Taking JVs Public

| JV IPO Examples: 1990-2020 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Amundi (fund management) | 2015 | $ 8.04 BN* |

| Asaleo Care (hygiene products) | 2014 | $ 1.4 BN* |

| Change Healthcare (healthcare IT) | 2019 | $ 807 MN |

| Coca Cola Femsa (bottler) | 1993 | $ 150 MN |

| Airbus** (defense) | 2000 | $ 3 BN |

| EDF Energies Nouvelles (renewables) | 2006 | $ 449 MN |

| Enerjisa (power) | 2018 | $ 474 MN |

| Evolent (healthcare IT) | 2015 | $ 225 MN |

| Nyrstar (zinc smelting) | 2007 | $ 2.3 BN |

| Orbitz (online travel site) | 2003 | $ 317 MN |

| Petro Rabigh (petrochemical) | 2008 | $ 1.2 BN |

| SBI Life (insurance) | 2017 | $ 1.3 BN |

| Safaricom (telecom) | 2008 | $ 3.06 BN* |

| SMN Power Holding (power) | 2011 | $ 106 MN |

| Spansion (semiconductors) | 2005 | $ 506 MN |

| Starbucks Japan (retail) | 2001 | $ 108 MN |

| Star Petroleum (refining) | 2015 | $ 1.08 BN* |

| Virgin Blue (airline) | 2003 | $ 1.6 BN* |

| Visa (payments) | 2008 | $ 19.1 BN |

| *Valuation at IPO; in other instances indicates approximate amount raised **Went public as EADS, and changed corporate name to Airbus in 2017 |

||

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

Despite the attractiveness of an IPO, however, fewer than 5% of JVs have pursued this path. While the IPO option isn’t always the right approach – as we explain below – we think that the paucity of JV IPOs also represents some missed opportunities: owners not appreciating the potential, deal makers not building in appropriate terms at the outset, and JV directors not migrating the operating model in a way that makes an IPO a more feasible option down the road.

The purpose of this article is to provide shareholders, directors, and JV CEOs with a set of practical guidelines for when – and when not – to IPO a JV, and how to prepare a JV for an IPO in 2021 and beyond, if desired.

WHEN – AND WHEN NOT – TO IPO A JV

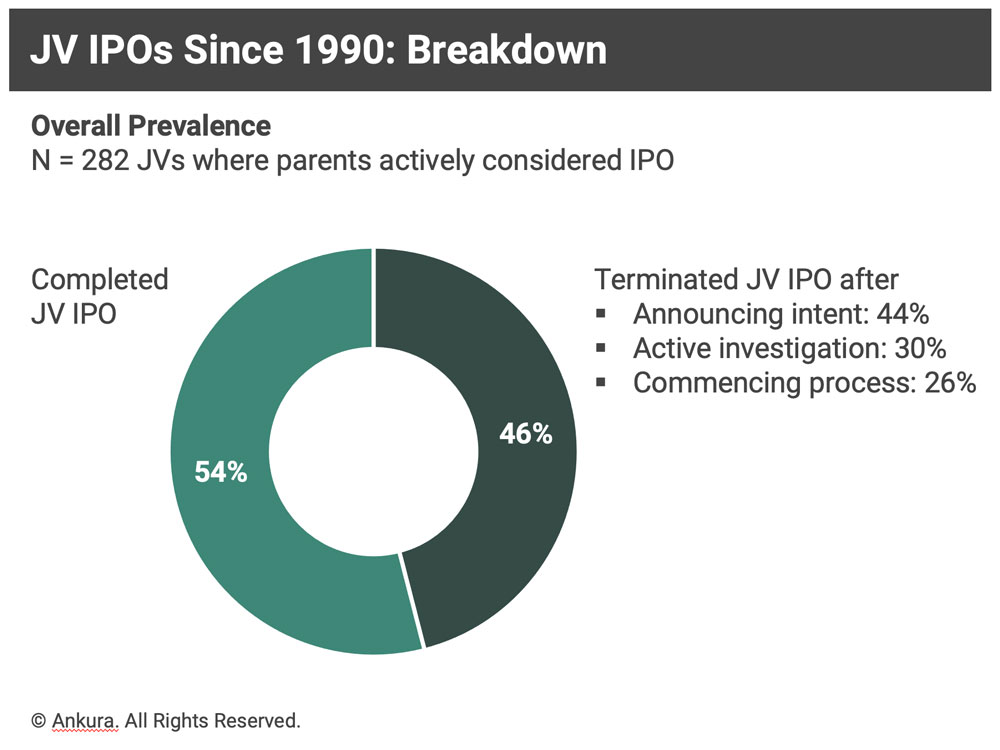

In developing this article, we researched IPOs of joint ventures going back to 1990, and assembled a dataset of almost 300 JVs that conducted a full public listing, a partial public listing (i.e., less than 100% of common equity), or had corporate parents who seriously considered – to the point of public announcement – but ultimately chose not to IPO (Exhibit 2). Our assessment included JVs across a range of industries – with 35% in the tech, media, and telecoms space, and the rest evenly distributed across sectors like consumer goods, oil and gas, and financial services – and across all geographies, though notably almost half of all JV IPOs occurred in Asia.

Reasons to pursue an IPO. Cash to the parent companies is an obvious motivator. In the JV IPOs in our dataset, the amount raised by the IPO ranged from less than $100 MN to more than $19 BN. Indeed, Visa’s IPO raise of $19.1 BN still ranks as the second largest IPO in American history (and sixth largest globally), and there are many other JVs whose IPOs revealed multi-billion-dollar market capitalizations.

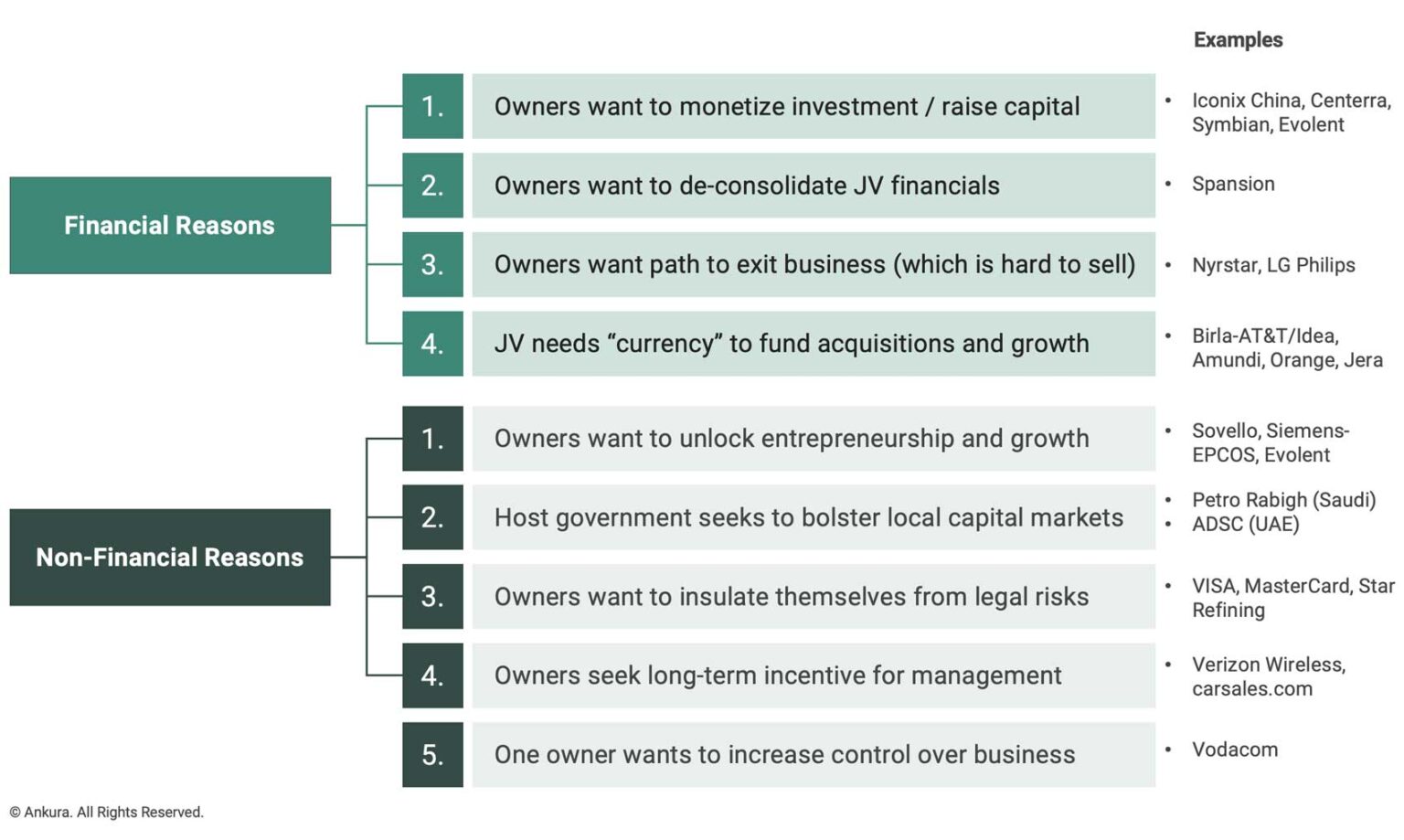

Unlocking market value and cash, though, is not the only – or even the dominant – reason for taking a JV public (Exhibit 3). Instead, other financial and non-financial factors were primary drivers in more than half of the IPOs in our dataset. On the financial side, executing an IPO of a JV can enable a parent to deconsolidate the results of a JV from its corporate financial statements, which can be especially attractive in cases where the JV is in startup phase with lower margins. For example, AMD was able to deconsolidate the losses from Spansion, its semiconductor manufacturing JV, by spinning off Spansion via IPO and treating its shareholding in the newly independent Spansion as a minority investment. An IPO can also enable access to capital markets by the JV, allowing a JV to self-fund ambitious capital expenses, as was the case in the IPO of the Petro Rabigh refining company by parent companies Saudi Aramco and Sumitomo, or to enable inorganic growth by using shares rather than cash for acquisitions, as was the case in the IPO of Amundi, a European asset management firm. More generally, partially divesting a JV through an IPO can be a way to efficiently restructure holdings in mature or non-core assets without immediately losing the positive financial impact of the JV. This was the case in the IPO of the LG Philips LCD manufacturing JV, which allowed Philips to progressively reduce its exposure in a business that performed well but was increasingly considered non-core by its shareholders.

Exhibit 3: Reasons to IPO a JV

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

Sometimes, non-financial reasons trigger the decision to pursue an IPO. Regulatory and antitrust issues are often important. For example, the IPOs of MasterCard and Visa were helpful in creating a degree of separation and independence from their bank owners, responding to concerns expressed by regulators and antitrust authorities, and the IPO of Star Petroleum helped Thai state-owned energy company PTT to reduce domestic anti-trust concerns in the refining sector while retaining a stake in the performance of the business. Several governments use IPOs to bolster emerging capital markets – for example, India and Saudi Arabia have pursued partial IPO of JVs between state-owned enterprises and private companies. Finally, the desire to “create space” from corporate parents for a new business that may be noncore, or requires a different management style and culture, is often in play. For example, the solar-producing joint venture Sovello, between Q-Cells and others, stated it was considering an IPO to support its rapid growth and enable it to operate more independently from its parents. Others like Evolent Health, a JV between the Advisory Board Company and University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, and Amundi have stated that an IPO is a critical branding tool that enables market awareness they exist (and are different from their parents), provides credibility, and reduces their marketing requirements.

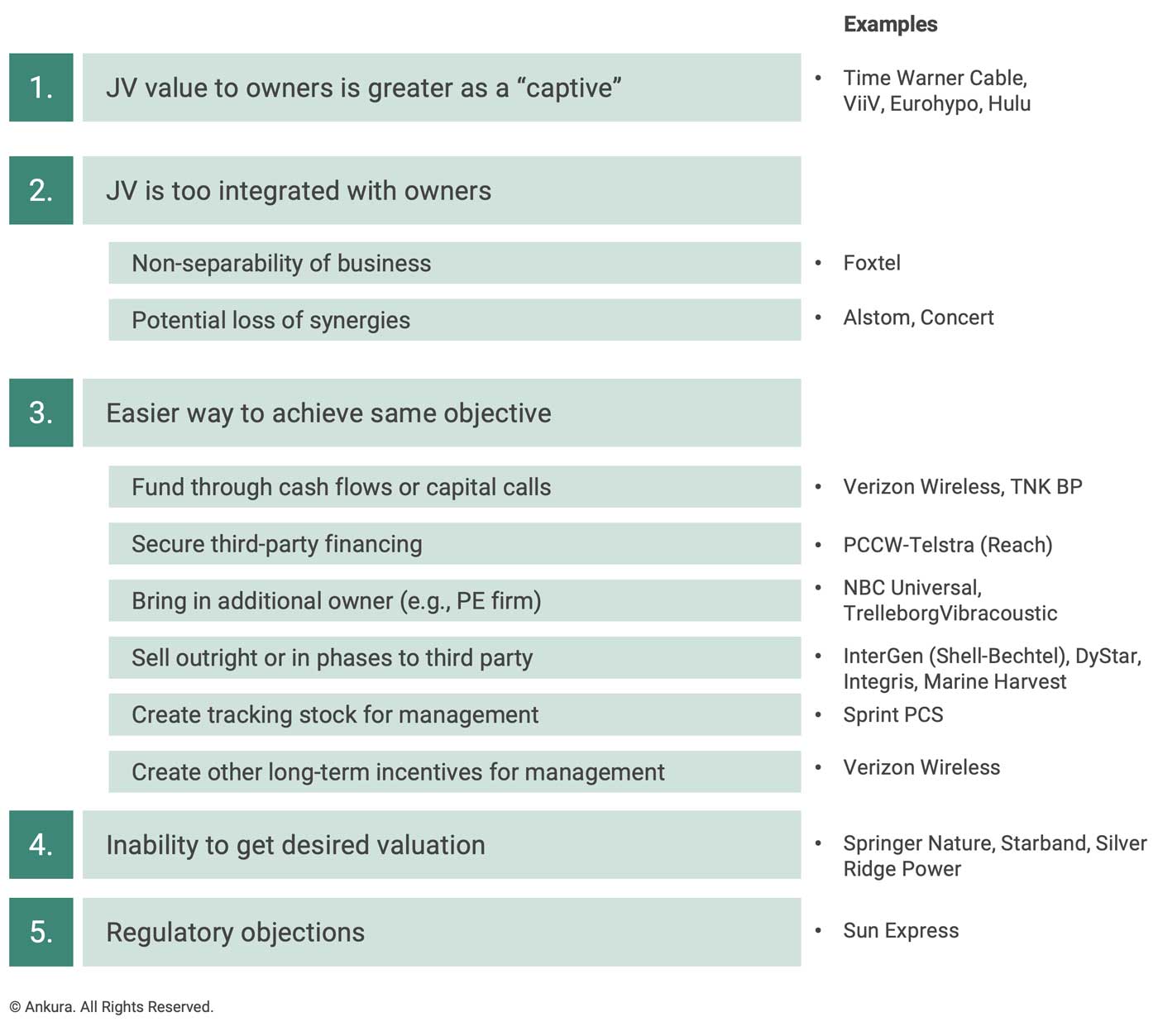

When not to pursue an IPO. Even when some of the motivations above are in play, there are three powerful reasons not to pursue an IPO of a JV (Exhibit 4):

- The JV’s value to its parents is greater as a “captive” than as a fully independent entity. For example, a healthcare IT JV in the US with access to a large volume of retail pharmacy transaction information and data on patient compliance with medication regimes also had a solid P&L, featured a strong management team, and was seen as a potentially attractive IPO candidate by its owners. But the JV’s indirect P&L benefit to the owners – by tailoring certain types of data collection that allowed the owners to dramatically reduce costs in their core healthcare business – far outweighed the potential direct benefits of capitalizing the JV, and an IPO carried the real risk that these indirect benefits would be de- prioritized. As a result, the owners decided to keep the business under their wings as a JV.

- The JV is too integrated with the parent companies to be separated, or too important to other parent businesses to be made independent. Many JVs are set up to execute a single value chain function like manufacturing product for parent offtake or marketing and sales of parent products. In these cases, IPOs may not be attractive to outside investors, because of the JV’s foundational dependence on parent companies, and because the desire for control on the part of the parents is greater than could be obtained with public shareholders.

- There’s an easier, faster, or less risky way to achieve the same objective. Taking a JV public introduces complexity and risks – and there are often better ways for the operating partners to achieve the desired objective. For instance, if a full exit is desired, it is often easier and faster to sell the venture outright to a third party, as Bechtel and Royal Dutch Shell did by selling their power utility JV Intergen to a private equity firm. Likewise, if a potential IPO is seen as a way to raise capital to fund growth, expansion or restructuring, third party or parent borrowing may prove far easier. And if the primary motivation is to create long-term incentives for management that match the power of stock options at publicly-traded firms, there are various approaches to create equity-like incentives, such as phantom equity, multi-year bonus payouts, and so forth.

In many of these situations, especially where the JV has more value as a captive, or is highly integrated with parent company activities, the best buyer – if the JV is to be sold – is usually one of the parent companies (and not the public) – which fits with the historical pattern that 80% of JVs that terminate end in an acquisition by one of the parent companies.

PREPARING FOR AN IPO

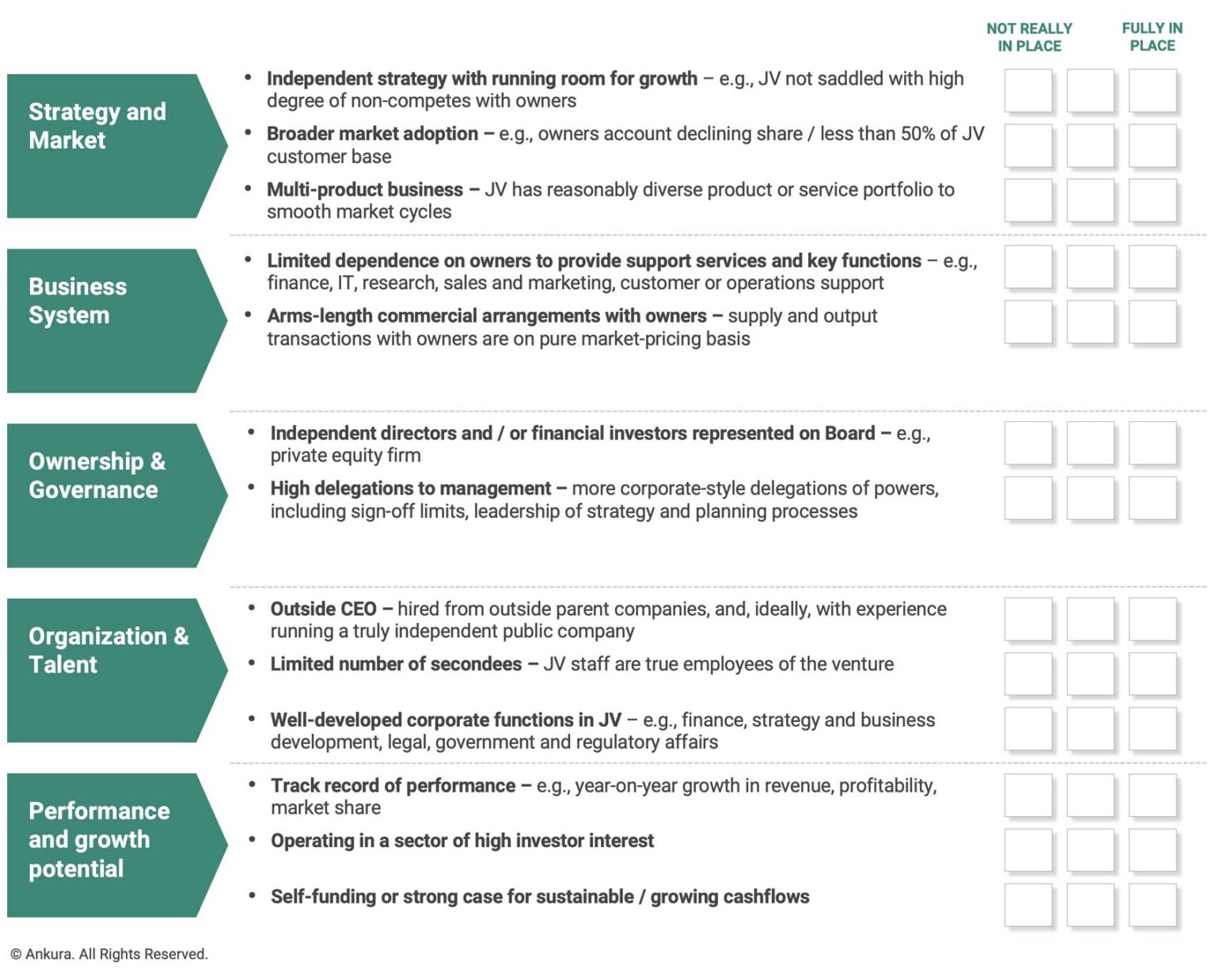

For most JVs, the path toward an IPO is measured in years, not months. The requirements for IPO are ones that typically require Board alignment and deliberate action – as well as some adjustments in the JV operating model. Based on our assessment of JVs that successfully pursued IPOs, Boards and corporate parents that wish to create the option for a JV to go public should put five building blocks in place (Exhibit 5):

Exhibit 5: Key Considerations – Preparing for an IPO

First, enable the JV to have its own independent strategy with sufficient running room for growth. The JV must have its own competitively viable strategy. A key issue here is enabling the JV to have enough running room – in terms of product market growth, technology, and pricing freedom – to be attractive to investors. The JV typically must graduate from depending on the owners for a large share of sales, and should preferably have a broad customer base with several product lines.

Second, separate the JV’s business system as much as possible from parent company support, and shift to true arms-length relationships between the JV and parent companies. To enable a future IPO, it is important to reduce the dependency of a JV on parent companies for technology, inputs, marketing / sales, and shared services. As an example, Spansion, whose Board decided to pursue an IPO, tried to develop a truly integrated JV business system, by transferring all related parent assets into the venture, and structuring commercial relationships with parents on an arms-length basis. By contrast, a JV whose profits or processes are compromised because of pre-existing agreements with parent companies will be less attractive to outside investors – and may run afoul of requirements for shareholder protection.

As a side note, corporate parents that are considering a partial IPO should beware of ending up “in the middle” – with neither a controlled entity, nor a company that can compete against fully independent players. The governance of partially public ventures – with two or more strategic owners and public shareholders – has a set of special challenges that must be carefully planned for and managed.

Third, the JV Board and owners should shift toward a “manager-managed” governance model, more like that of an independent company than the typical JV. This includes, for example, relatively high delegations of formal and informal power to the JV management team; a Board that spends most of its time on strategy, growth, investment decisions, and talent issues – not detailed performance management or operational reviews. In the “manager-managed” model, the owners may also add independent directors to the Board, and reduce sharply the typical long list of issues that require supra-majority voting. For example, when Société Générale and Calyon formed Newedge, their global brokerage JV, they planned for an IPO within 24 months, and so structured it as an independent entity with a high degree of operational freedom for its management team, and with an independent non-voting observer on its Board (though to reinforce an earlier point, the IPO was scrapped in favor of a full buyout by Société Générale).

Fourth, the JV Board should support the CEO in building a deep and independent bench of talent, with attractive and performance-focused incentive programs. As we’ve written elsewhere, the compensation of most JV CEOs – and that of JV executives in general – is lower than what is seen in public companies.[1]See “Show Me the Money: JV Executive Compensation,” The Joint Venture Exchange, January 2011 As a JV prepares to IPO, the pressures for growth and performance increase, as do the requirements for the company to have its own full set of corporate capabilities including shareholder relations. While the IPO can provide a powerful growth story to attract managers, it is usually necessary to redesign the compensation system, shifting toward performance-based incentives, and adding a long-term incentive program. To attract strong executives, some JVs have added stock options for the top 5-10 managers as much as 5 years before an envisioned IPO, as a way to help build the bench at the venture and keep JV management focused on the requirements of the IPO.

In addition, JVs that wish to pursue an IPO would be well-served to have an outside CEO, to limit the number of secondees from the parent companies, and to build internal capabilities in strategy, business development, finance, legal, and external affairs.

Fifth, the JV should be managed so as to build a strong financial track record and balance sheet, or a very compelling case for future profitability and cash flow. Many JVs are run as assets, not businesses – and objectives may be defined in terms of capacity utilization, production volumes, or cost efficiency. To evolve toward an IPO, a JV should be a true P&L-focused entity, with strong cash flows. In general, the JV should be structured so that it is self-funding, or is able to show a strong case for sustainable cash flow. Usually, the amount of transparency will need to be dialed up from what’s mandated for JVs, in order to give outside investors confidence in the performance and prospects of the venture.

It’s worth noting that many of these changes are good things to do – whether the parent companies in the end decide to go for an IPO or not.

We continue to expect a steady trickle of IPOs of JVs in the next 3-5 years. This will be driven by a number of converging factors: a need to monetize investments in JVs to help weather market downturns, the desire of emerging market governments to privatize current JVs that are partly owned by state-owned enterprises, and the coming of age of many JVs that are today in their adolescent years. We don’t think IPOs are suitable in all cases – but our analysis indicates that successful JV IPOs will be the result of decisive actions on strategy, operations, and governance by their Boards.

Comments