Managing Misalignment in Joint Ventures

JV agreements can be tailored to more effectively prevent, de-escalate, and resolve disputes.

By seriously considering the prospect of JV failure upfront, companies can take action before it’s too late.

FEBRUARY 2016 — Joint ventures have a bad reputation. While we believe that the drawbacks of joint ventures are sometimes over-stated, especially among companies that have limited experience with them, JVs remain a transaction structure that too often leads to underperformance, inefficiency, and failure. As one public company CEO once told me: “I’m certain that JVs were created by the Marquis de Sade as a special type of torture reserved for corporate executives.”

The list of failed, underachieving, or just good-old-fashioned painful JVs could fill a phonebook (Exhibit 1).

65:35 media-streaming and DVD rental JV between Verizon and Outerwall in which the partners agree to invest up to $450M; dissolved in 2014 due to inability to compete against Netflix (2012–2014)

50:50 JV to distribute Tiffany-branded watches through Swatch’s retail channel; terminated in 2011 due to weak consumer demand; litigation between the partners resulted in Tiffany’s paying a $449M settlement to Swatch (2007-2011)

50:50 JV to build and operate cash and carry superstores in India. JV unwound due to changing rules on foreign investment, an internal bribery probe, and a faltering partnership. Walmart paid $334M to buy out Bharti’s share after losses of $151M (2007-2014)

43:57 Chinese baby formula JV; bankrupted in 2009 after melamine baby formula contamination, leading to Fonterra, the world’s leading dairy company, to write off $200M investment loss (2005-2009)

High-profile 50:50 JV that consolidated Sony and Bertelsmann’s music businesses; failed due to sharply divergent views of the industry, cultural differences, and market dynamics; bought out by Sony (2004-2008)

Motorola-led satellite-based wireless phone JV with 19 partners across 160 countries; $5B investment; significant issues with technology and target market definition; filed for bankruptcy a year after launch, in one of the largest bankruptcies in U.S. history (1998-1999)

Global telecom JV among Deutsche Telekom, France Telecom, and Sprint to boost their international operations; dissolved after low earnings, acrimonious partner relations, and outside mergers (1998-2002)

50:50 Indian motorcycle JV that failed due to poor consumer demand for F650 super bike (1995-1996)

Source: public filings and press reports; Ankura analysis

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

How do companies avoid this fate? We have built a career advising companies how to design, structure, govern, and manage joint ventures and other alliances. And we have come to believe that many considerations – from strategy, partner selection, contractual terms, venture governance, organizational design, and management – coalesce to determine whether a JV meets or exceeds its shareholders’ expectations, or whether it limps toward the horizon or collapses under its own weight.

That said, one tool merits more attention: The JV Pre-Mortem. Many companies conduct post-mortems on failed projects. And many companies conduct some form of “look-back” or post-investment appraisal on acquisitions, joint ventures, and other investments. But how many companies think seriously upfront about the prospect of joint venture failure – and then try to do something about it before it is too late? Not many.

The idea of a JV Pre-Mortem is simple: While negotiating with the counterparty, carve out a bit of concentrated time with your team to consider failure. The idea is to imagine a future where the JV fails – and to think about what might have caused it. It’s like the old adage to “imagine your own funeral” applied to a joint venture. Unlike a post-mortem – which may help science and future generations but doesn’t do much good for the patient – the pre-mortem helps avoid failure on what the team cares most about: the current JV. The JV Pre-Mortem is a JV- specific application of a concept developed by Gary Klein, a pioneer in decision science. Klein has argued that a pre-mortem temporarily reverses the culture of the team – where everyone is pegged on success and creative solutions, and skeptics are viewed with some disdain. In a pre-mortem, this culture is flipped on its head, and the smartest guy in the room is suddenly the one who has the sharpest view on what could cause failure.

Conducting a JV Pre-Mortem is not complicated (Exhibit 2). It works like this: Assemble everyone in your company who is meaningfully involved in the JV – the executive sponsor, members of the deal team, key functional executives, lawyers and finance staff, future board members, and those who might be tagged to run the JV post-close. Carve out two hours from 12:00 noon to 2:00 pm, and buy them lunch. (Food will get them to relax and think creatively.)

| WORKSHOP | TIMING | |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction | Introduce the team, explain the context and purpose, then set the stage for the futuristic scenario that the JV has failed | 15 Minutes |

| Brainstorming | Ask individuals to brainstorm list of creative reasons why JV failed | 10 Minutes |

| Whiteboarding | Go around room asking each person to provide one reason for JV failure; write reasons on whiteboard until ideas run dry | 15 Minutes |

| Additional thoughts | Ask group whether the existing list has sparked other thoughts and cycle. Stop generating ideas by 1 hour mark | 20 Minutes |

| Categorization | Categorize reasons for failure and determine likelihood and level of control | 15 Minutes |

| Solutions | Generating ideas for how to address these failures | 45 Minutes |

| Source: public filings; Ankura analysis © Ankura. All Rights Reserved. |

||

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

Once everyone has arrived (the meeting should take place in person if at all possible), set the scene. Explain that we are now living in the future and the JV has failed. That the JV has failed is beyond question. Now ask everyone to spend 5 to 10 minutes writing down a list of reasons for why the JV failed. Ask people to be thoughtful and imaginative. Next, go around the room and ask each person to provide one reason for the failure. Write the reasons on a board. Keep going around the room until all ideas are out. Have someone do nothing other than take notes. Ask the room whether the list of ideas has sparked other thoughts that should be captured. Stop generating ideas after 60 minutes.

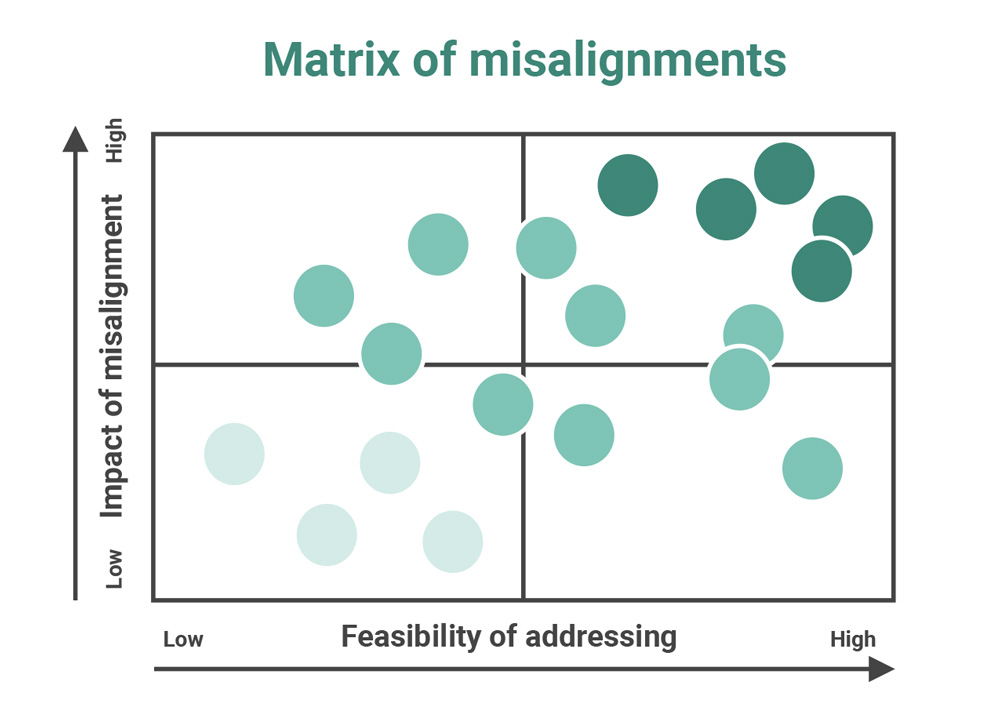

Now spend 15 minutes categorizing the reasons for failure. Does the group believe that certain failure stories are more realistic, while others are highly unlikely? Focus the discussion on the more likely reasons for failure. Of these, are certain failure scenarios purely externally-driven (e.g., entry of a new competitor, change in regulations) or things that the team can do nothing about (e.g., failure of the technology)? Are others things at least partially-within the team’s control (e.g., partner choice, failure of the partners’ to fund the JV’s growth into new markets)? Focus on those within the team’s control.

From this list, generate the 10 most likely reasons for failure. Finally, spend the last 45 minutes generating ideas for how to address these failures. The solutions might be found in overall deal design (e.g., authorized scope, operating model, ownership split) or specific contractual terms (e.g., IP rights, exclusivity, financial incentives for one shareholder sales organization to support the JV). Or solutions might relate to choice of partner. Or they might relate to risk management and assurance policies (i.e., extent to which the venture meets the company’s HSE or financial control standards). Or they might relate to governance or organizational practices (e.g., board composition, caliber of senior management seconded into the venture, use of lead directors, how the JV connects with each shareholder’s corporate strategy and review processes).

If the creative juices dry up, the facilitator might expand the frame by introducing structure for different types of solutions. When we do this, we will simply write on a white board seven seven categories of solutions: business strategy, partner choice, deal concept, contractual terms, risk management and assurance policies, and governance and organizational model.

Once done, send everyone on their way. But have one person (e.g., a core member of the deal team) soak in and synthesize the ideas, and propose how to translate the best of them into practical changes to deal terms or other elements of the venture. Depending the size and risks of the venture, that person might supplement this workshop input with additional analytics. This might include refining the failure scenarios by reviewing similar ventures that the company, counterparty, or industry peers have done, and looking for patterns of problems. Or it might include conducting what we call “misalignment scenario planning” – an analysis that looks closely at a major category of JV failure (misalignment), disaggregates it, and seeks solutions. In some cases, the company might consider conducting a JV Pre-Mortem with the potential partner. This exercise might be done in lieu of – or in addition to – a Pre-Mortem just with the internal team.

Gandhi told us to “live like you are going to die tomorrow, and learn as if you are going to live forever.” That’s the JV Pre-Mortem in a nutshell.

In certain situations and corporate cultures, a more rigorous JV pre-mortem may be in order. Rather than simply asking people to show up and be thoughtful (a big enough ask in many companies!), the expectation is for participants to do some thinking ahead of time. When we facilitate such sessions, we’ll include templates to help people to organize their thoughts around a few questions, including:

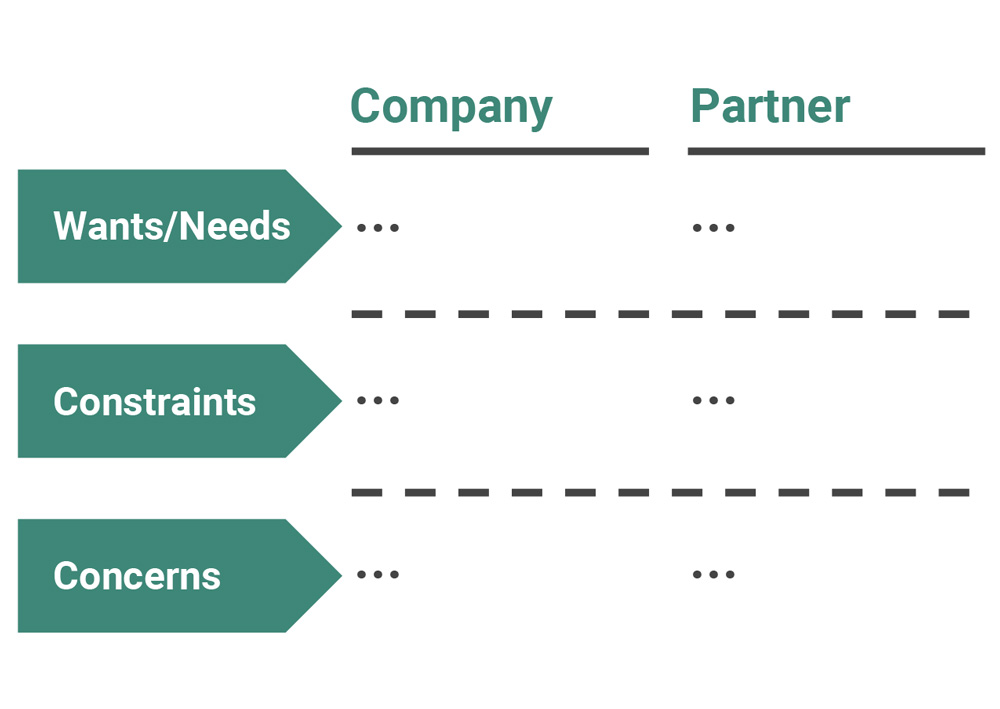

What are the company and counterparty’s wants, needs, concerns and constraints?

What are the 5 or 10 most likely issues (e.g., expansion into new markets, funding of future capital investments, dividend policies) where the partners might become misaligned?

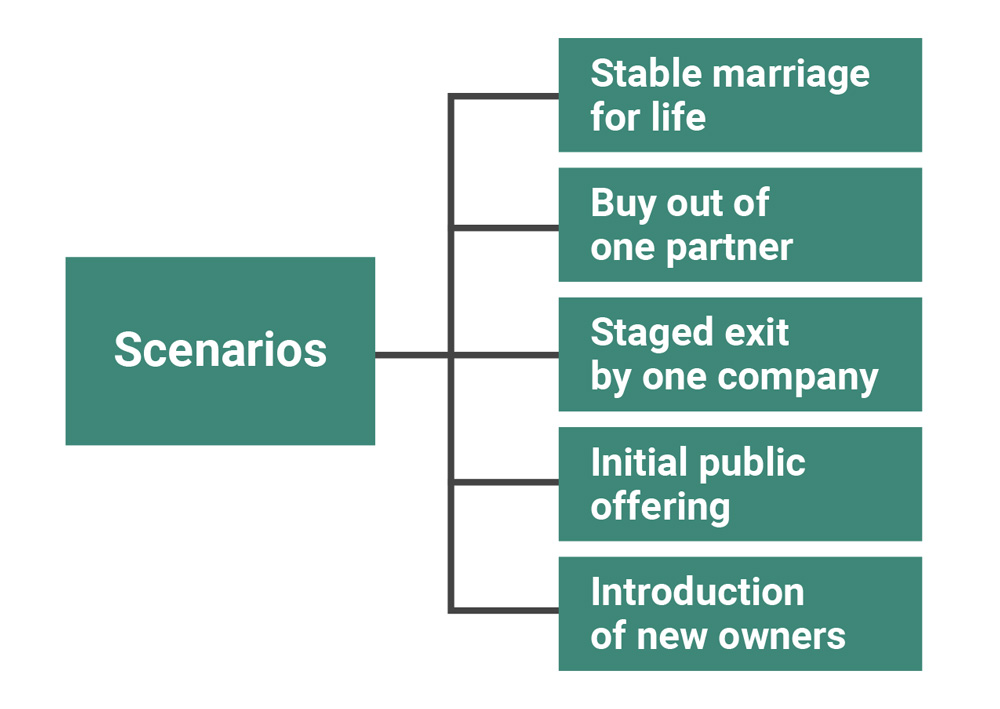

What are the potential evolution scenarios for the venture in terms of ownership – i.e., stable marriage for life, buy out of the partner, staged exit by the company, IPO, introduction of additional owners, etc.?

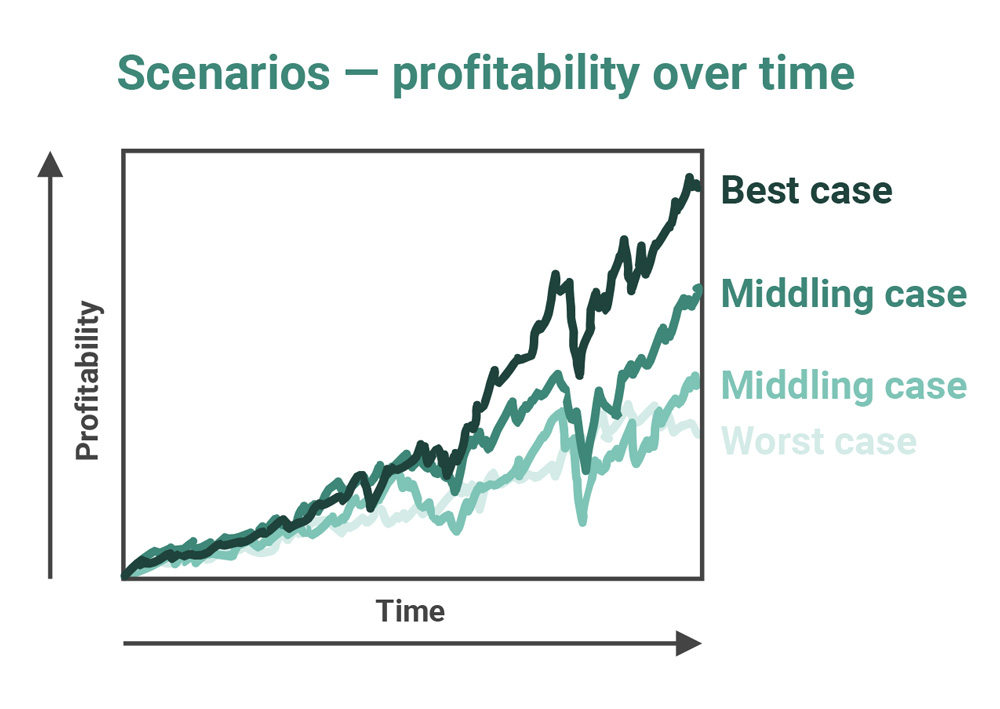

What are the different outcome scenarios for the venture? Beyond wild success (often as envisioned in the deal team’s financial model) and abject failure, what are the more realistic “middling” success or “mild” underperformance scenarios in three to five years – and will the companies likely react to such outcomes?

This last point was a theme a few weeks ago at a joint venture conference in New York. Speaking of his experience negotiating almost 30 JVs and partnerships, Tom Finn, President of Procter & Gamble’s Global Health Care Business, said, “All too often the people working on the deal image just one or two scenarios – incredible success, and maybe failure. But what happens if the future scenario is different – that the JV is a medium success, or a little success but a going concern? How are we going to deal with that?”

Source: Ankura analysis

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

We understand that succeeding in joint ventures and partnerships requires a blend of hard facts and analysis, with an ability to align partners around a common vision and practical solutions that reflect their different interests and constraints. Our team is composed of strategy consultants, transaction attorneys, and investment bankers with significant experience on joint ventures and partnerships – reflecting the unique skillset required to design and evolve these ventures. We also bring an unrivaled database of deal terms and governance practices in joint ventures and partnerships, as well as proprietary standards, which allow us to benchmark transaction structures and existing ventures, and thus better identify and build alignment around gaps and potential solutions. Contact us to learn more about how we can help you.

Comments