[Infographic] Independent Perspectives Prove Effective in Resolving JV Disputes

98% of disputes that have been referred to a dispute review board do not proceed to arbitration or litigation.

Deal flexibility is both a blessing and a curse for JVs. Here are our tips for structuring a durable JV with a strong chance of success – and for getting to a “quick no” or a “good yes.”

JULY 2016 — RARELY A DAY PASSES without a new joint venture being announced in the world’s leading financial publications. In the last year, Apple, Bank of China, Google, ExxonMobil, IBM, Microsoft, Nestlé, Novartis, Samsung, Sinopec, Tesla, Toyota, and many other leading companies entered into at least one new joint venture – and in some cases several. The Ankura Joint Venture Index shows that deal volume has remained consistently high in recent years, which is not surprising given that joint ventures allow companies to access capabilities, enter new or restricted markets, share risk, pool capital, and secure scale- and scope-related synergies.

"*" indicates required fields

But the great advantage of joint ventures – the freedom to combine contributions of two or more players in creative ways – also makes these deals inherently challenging to negotiate and structure compared to, say, acquisitions or licensing agreements. The flexibility of joint ventures requires dealmakers to make design choices on multiple dimensions, including asset and value chain scope, operating model, exclusivity, contributions, ownership, branding, IP rights, governance, financial arrangements, management and staffing, and exit.

It can be a demanding task.

On the following pages, we offer a five-part checklist that can be used to pressure-test new joint venture deal concepts and to negotiate and structure JV legal agreements. We also offer some advice on how to ensure that the JV negotiation process leads to either a “quick no” or a “good yes.”

Over the years, we have advised on more than 600 joint venture transactions and conducted dozens of research studies on what makes for successful deals. At the most fundamental level, we’ve found that joint venture dealmaking success hinges on five critical elements (Exhibit 1), each of which introduces questions that need to be addressed in the design, structuring, and negotiations of a new joint venture.

The deal rationale should be tested on two dimensions: the choice of JV vs. other structures, and the strategic and economic case for the JV. A JV should only be pursued if it is a better vehicle than other strategic options – or is the only viable way to pursue an attractive business opportunity. There are many simpler business arrangements, including supply, distribution, marketing, and licensing agreements – that involve substantially less shared control and complexity. If any of these deal options will accomplish the objectives with similar results, it should be preferred, since a JV will consume a significant amount of management time and expense in its setup and ongoing governance.

Similarly, a straight acquisition is preferable when it’s possible to acquire a target company or asset and synergies are large enough to recapture the expected control premium. Often, a JV is a compelling “second best” to an acquisition if the desired target can’t be acquired – for example, when a family-owned business won’t sell but is willing to enter into a JV, or when an emerging-market is a great growth opportunity but regulations require that a local partner own 50+% of a business. Conversely, a company might be better off entering into a joint venture as a “staged exit” if, for instance, it cannot reach agreement with the counterparty on an acceptable valuation of the assets or business. In these cases, a JV should be structured with evolution toward a full acquisition in mind.

The rationale for a joint venture – strategic and economic success metrics – should be sharply stated in ways that can be tested with the partner (e.g., market share of 15% in 5 years, combined parent cost savings of $150 million over 2 years).

The JV economic case needs to be quantified to complete the assessment of the deal rationale. A few points are worth keeping in mind. First: the fact that a partner may be putting up 50% of the capital doesn’t mean that there is any less burden of proof on the investment analysis. (Indeed, for consolidation-type JVs, our rule of thumb is that most JVs should create at least 20% in incremental value above the standalone value of the assets contributed, in order to more than cover the added governance burden.) Second: beware of the potential JV built on achieving strategic goals but with a weak financial case. We have found this to be especially prevalent in JVs formed to satisfy regulatory restrictions on foreign ownership. While it may be wise to enter a JV for strategic reasons, sponsors and dealmakers need to present a clear articulation of the strategic (non-financial) drivers, have an eyes-wide-open discussion that these strategic drivers (and not an inflated financial case) provide sufficient benefits to proceed, and describe how success against these strategic drivers will be measured and tracked.

Partner screening should begin with partner capabilities – the geographic, product, or functional strengths that the potential partner will contribute – which are core to the reason for selecting them as JV partners. The assessment of capabilities should also include reviewing the financial performance of potential partners, since JVs between partners that are strong financial performers are more than twice as likely to succeed as compared to those that involve less-than-average performers in their industry.

JVs between partners with different product markets and functional capabilities perform better than JVs between partners with similar capabilities, except for consolidation JVs, where the parents are fully merging assets into the JV. In fact, JVs between companies that have similar product markets and functional strengths – which are often competitors – are more likely to lead to tensions after the JV is formed because the partners are natural competitors and may seek to play similar roles in the venture.

Assuming the partner has the needed capabilities, compatibility should be judged based on the dimensions of culture and values. A systematic assessment of the key attributes of a partner’s company culture can quickly reveal if there are likely to be major issues. For example, an organization that is heavily process-oriented will not be a good match for a highly entrepreneurial company.[1]Please see “Succeeding in Cross Cultural Joint Ventures,” The Joint Venture Exchange, October 2010 and “JV Partner Screening Process (Practitioner Guide).” Also see “The Six ‘Cs’ for … Continue reading

The fit of values is essential, and should be tested with an assessment of the partner’s most important corporate values, as well as their reputation with business partners, customers, and suppliers. As negotiations progress, the policies of the partner with respect to environment, safety, health, and corporate social responsibility should be reviewed for consistency with the company’s own policies and beliefs.

Partners should also have a compatible long-term vision and strategy (i.e., whether the JV is intended as a growth business vs. a narrow-purpose entity). Many JVs between emerging-market and global partners have been stressed as the emerging-market partners wanted to expand the scope or their role in management of the JV. Some of these, like GS Caltex and Alcatel China, have been very successfully restructured and expanded over time; others have been unwound or bought out by one of the partners to resolve the friction.

The third “C” in partner screening is commitment, which is crucial to ensure follow-through after the deal is struck. Two good indicators of commitment are: the level of involvement of senior people in the deal process, and the partner’s willingness to name high-performing senior executives who will go into the JV after the deal is done.

The greatest benefit of the JV structure is that it can be tailored across many dimensions. A look at the table of contents of a joint venture agreement shows more than a dozen major deal clauses (Exhibit 2), each of which introduces a series of important questions. However, there is rarely a single best answer for how to structure a JV. Usually, there are several viable options, each of which has different pros/cons. For example, it is common to have a choice between a “lighter” structure (fewer value-chain activities in the JV), and a “heavier” structure (a more self-standing JV with its own assets, people, systems, and with a full value chain). More often than not, the lighter option creates less value but is easier to govern; the heavier option brings more potential value, but is harder to set up and to govern.

We recommend that deal teams: a) gain agreement on the criteria that will be used to evaluate deal options (e.g., value, feasibility, post-close manageability), b) identify key inputs (e.g., partner wants, needs, and constraints, tax, accounting and regulatory considerations; analogous transaction structures within and outside the industry), then c) develop alternative JV options creatively blending major deal terms, d) test these against a set of evaluation criteria and with the ultimate sponsors of the JV, and finally e) adapt and combine the options to create a best-of-breed hybrid. The initial options are usually characterized by differing scope and contributions (i.e., value chain, product, geography, technology), and/or by different governance models (i.e., independent JV; interdependent JV; JV that is operated by one of the partners). For example, in an emerging market hotel JV, we developed transaction structure options based on value chain scope – which parts would be in the JV versus which would be done by the parent companies. These competing options were then compared in terms of fit with parent strategy, value, and feasibility (Exhibit 3).

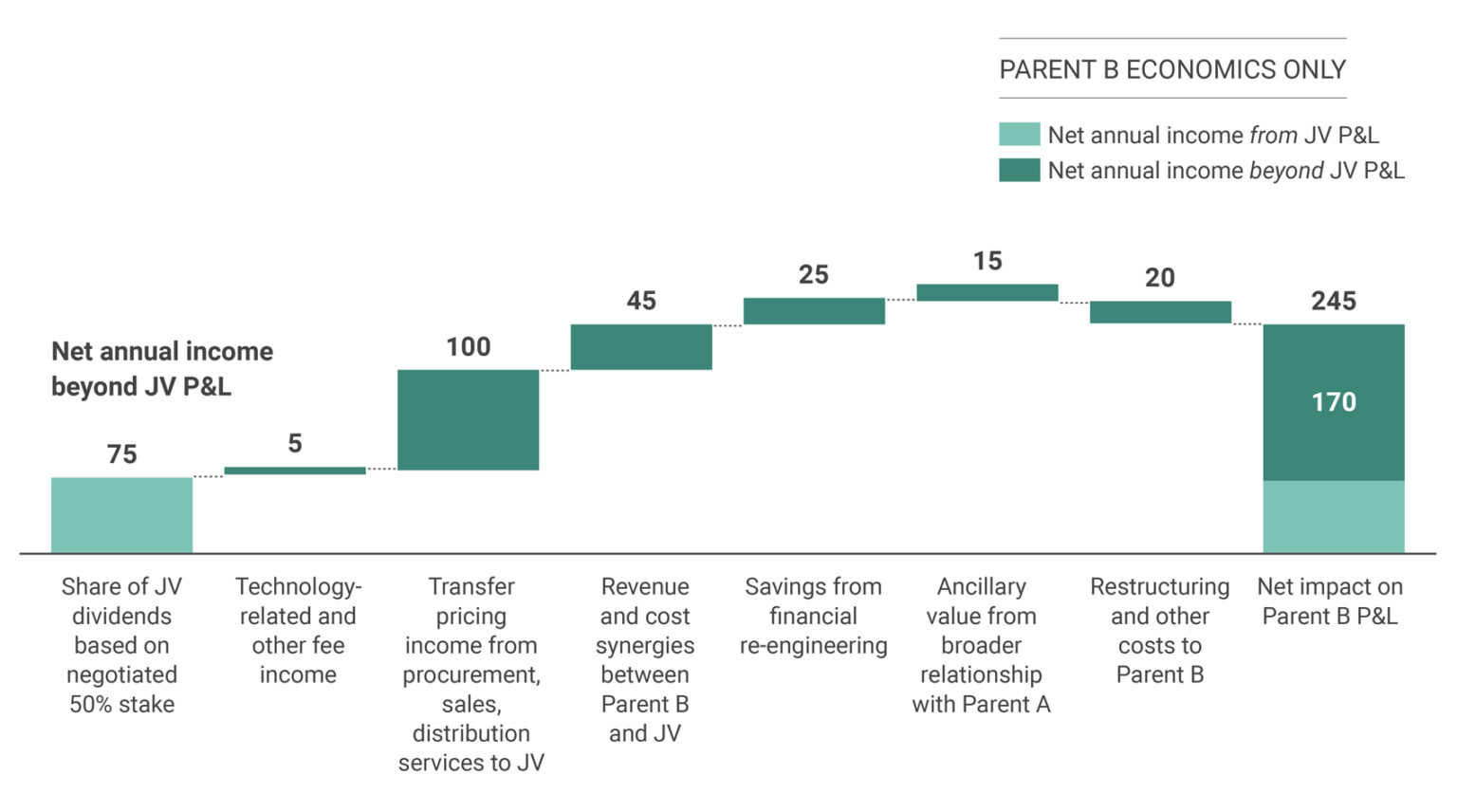

In M&A transactions, the focus on financial terms is on getting a good bargain at the outset – winning a zero-sum game of negotiation on initial value and price. While ensuring fair value for assets contributed is important, it often isn’t an exact science, given the intangible nature of contributions – know-how, access to customers, relationships, etc. In JVs, the focus needs to be on developing a fair approach to future value-sharing and aligning interests after the deal. This requires taking a close look at the integrated economics of the JV, including flows seen only at the parent-company level. Often, the total value seen by one or both parents may be very different from what they will receive from the JV P&L per se (Exhibit 4). Understanding the JV P&L is important, but often an equal or greater amount of value is recognized from JV-to-parent transactions. We refer to this as “total venture economics.” For example, one liquid natural gas JV generated $500 million in profits through its P&L, but supported more than $2 billion in downstream profits for the shareholders.

The JV deal negotiations should take this into account. For example, a company’s negotiating positions on ownership levels, shared service pricing and licensing fees, valuation of initial contributions, etc., should reflect this integrated picture of total venture economics – for both the company and the counterparty. Likewise, transfer pricing principles should be as fair and transparent as possible and ideally easy to compare to market rates or actual costs. These arrangements should be done in a way that will create incentives for the JV management team, i.e., not penalizing the JV top team for distortions in JV economics that are driven by transfer pricing rather than underlying operating performance.

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

The economic model for the JV itself – beyond the value-sharing between the parents – is a critical design choice that is sometimes given short shrift. Our benchmarking research has shown that the most successful JVs are those with a profit-oriented business model, where the JV P&L reflects the majority of value, and where the JV has the best chance to self-fund investments. But there are times when it makes sense to set up a JV as a “managed margin” or “cost center” model.

Managed margin economic structures are common in multi-partner JVs in financial services, healthcare, transport and other sectors where industry peers establish a JV to gain scale in a part of their business (e.g., back-office processing) and are customers of the venture. In such cases, the pricing to the owners is more important than JV profit per se. For these forms of JVs, it is critical to negotiate the terms under which additional investments can be made, i.e., whether one partner can elect to fund investments when other partners do not wish to put in additional capital.

The great challenge of JVs – control – comes in many more gradations than “I control,” “You control,” or “We share control.” For starters, it is worth keeping in mind that control need not flow directly from a valuation-derived ownership level. Many JVs have been formed over the years (e.g., MillerCoors and the Solae JV between DuPont and Bunge) with unequal investments that are governed as 50:50 ventures. Similarly, JVs can be structured to provide a minority or non-controlling partner with effective control over specific geographic markets, customer segments or business functions, such as product development, manufacturing, or regulatory affairs. For example, Volkswagen structured a minority JV in China to provide it with effective control over sales, distribution, and dealerships.

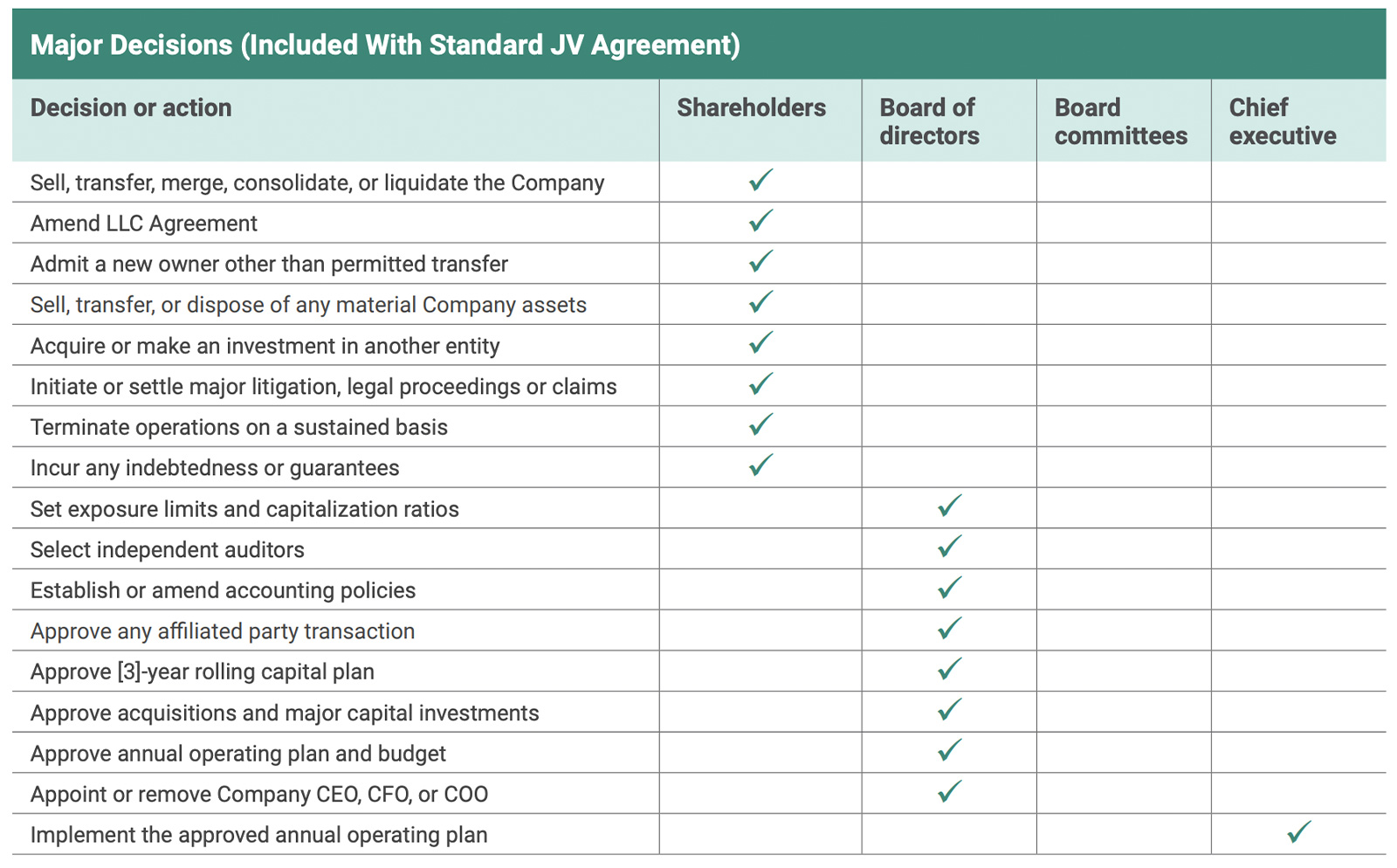

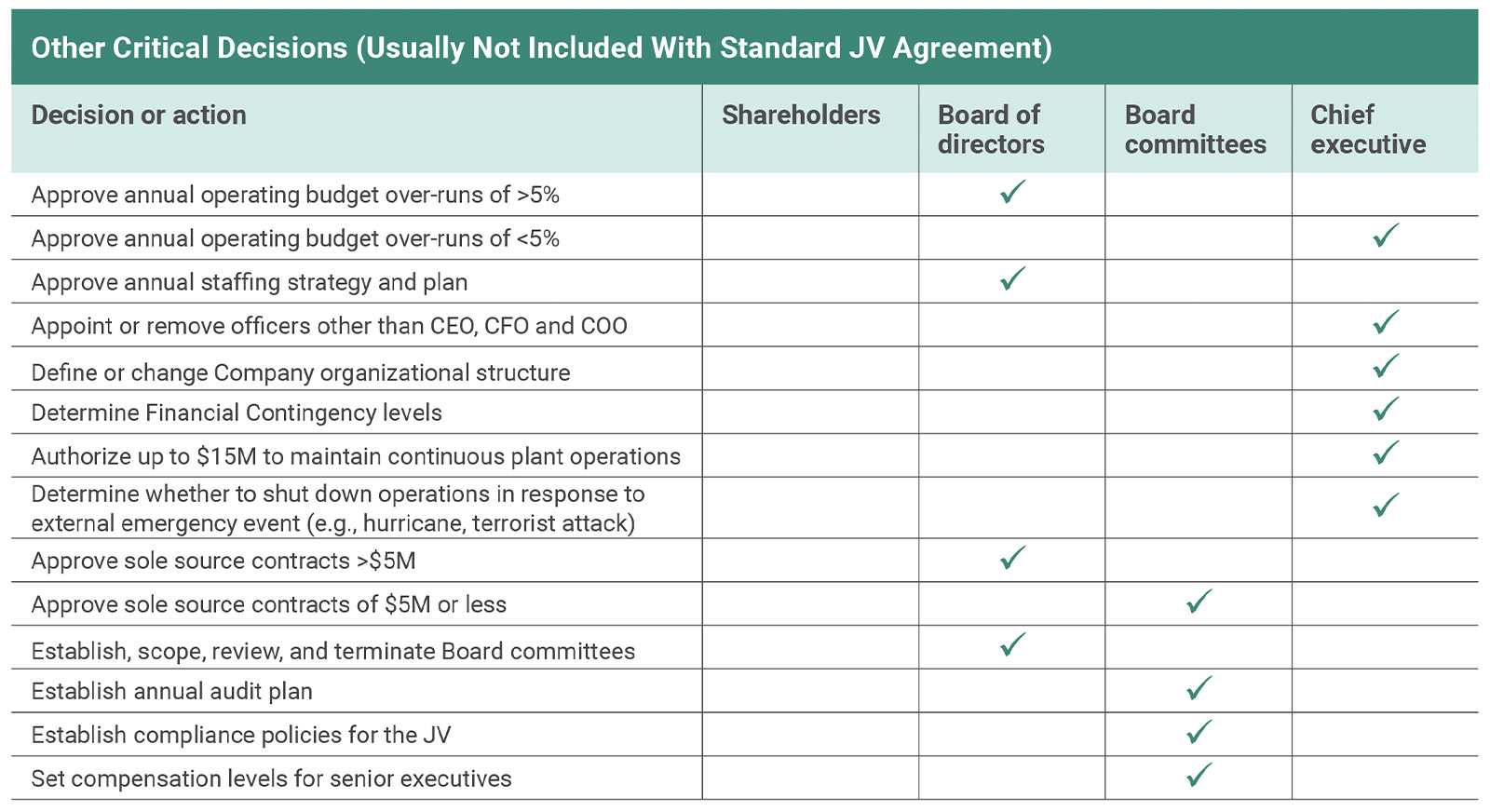

The standard voting- and control-related terms in a JV agreement usually do a good job spelling out where the most fundamental decisions will be made (e.g., shareholders vs. Board) and defining the voting thresholds needed to carry a decision (e.g., unanimous, supermajority, simple majority). Typically, these fundamental decisions relate to topics like liquidating the company, issuing new equity, changing the legal agreements, incurring indebtedness, and appointing the top officers of the JV. What we’ve found is that there is another level of more operational decisions that are rarely defined in the JV agreement, but that are critical to agree on in order for the venture to function (Exhibit 5). Defining and agreeing on these next-level decisions – including what authority is delegated to the JV CEO and management, and whether Board and non-Board committees will have any approval or vetting rights – is absolutely essential to rooting out potential misalignments and getting the JV off to a good start. Beyond powers and delegations, dealmakers should carefully consider Board composition and clarify which of the parent companies’ corporate standards, policies, processes, and systems the venture will be expected to adopt (or put in place those that are materially equivalent to the parents) versus where it has the freedom to develop its own approaches. This work does not need to be in painstaking detail, but it needs to be in enough detail to be able to operationalize the JV after the contract is signed without reverting to a negotiation mode.

Decision Making Powers – Illustration

Who will have the power to make what decisions?

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

Beyond the typical governance issues dealt with in the JV agreement, it’s also critical to decide on the staffing model. Will the JV be populated with JV employees and have its own HR and compensation system? If the JV senior team will be populated with secondees, the governance arrangements should ensure that secondees truly feel like they are working for the CEO. For example, the governance agreements could state that the CEO has hire, fire, review and compensation decision rights over all employees, whether seconded or not, and the right to interview secondees before they join the JV team. Failure to address these “beyond-the-contract” governance issues can be painful for all after the deal is done. For example, as a CEO said to us recently: “My COO was sent by one parent. He has powerful sponsors in that parent, his compensation will be set by the parent company, and he is the darling of one of the board members from that parent. He basically snubs his nose at me if he disagrees, and everyone in the JV knows it. He’s in a role that is critical to my success – so I’m starting to look at opportunities in companies that don’t have these types of joint venture problems.”

Our research suggests that JVs that are able to evolve their scope, structure, and governance are more than twice as successful as those that can’t (Exhibit 6). Yet virtually every JV gets “stuck” at critical inflection points – when the external market or the parent-company ambitions have changed, or after the JV accomplishes its initial objectives. Building in the capacity and flexibility to evolve at these points should be on the “must-do” list for dealmakers. There are a number of ways to build in flexibility to evolve, including, for example, “opt-out” provisions that allow one partner to proceed with investments if the other is not willing or able to contribute additional capital, provisions for adjusting service and input/output agreements, and so on.

But many JVs reach an inflection point or deadlock where the best move is to exit or unwind. 50:50 JVs are especially prone to deadlock. These risks can be addressed in a number of ways, including dispute-resolution mechanisms that don’t create a hair-trigger termination of the JV.

A JV negotiation team, with its legal and financial advisors, will often be tempted to quickly draft contracts and negotiate details. Instead, the deal team leaders should address the first two checklist items – deal rationale and partner fit – before much work is done on the deal elements that follow. When the rationale and partner fit are determined, the other three items should be addressed in parallel, with each being fleshed out in more detail as negotiations proceed.

A jointly-agreed upon “key business principles” document, which is shaped and approved by all critical decision-makers in both or all of the JV parent companies, is a great tool to ensure negotiations go far enough in designing a JV that can work beyond the formal legal agreements. This document can serve as a basis for legal drafting and the design of post-deal governance and organization of the JV.

As for the sequence of addressing specific deal terms, the deal leader must keep the team focused on critical issues early versus those that can be deferred (Exhibit 7). The trick is to address all of the must-have items within 2 months so that a deal is 90% assured before investing the 6-12 months that are usually needed to finalize a complex JV. Generally, early outputs should include 1) the product-market scope and parent contributions; 2) the split of ownership and profits; and 3) the overall governance approach, e.g., level of venture autonomy, staffing approach, etc. The best JV dealmakers distinguish themselves not only by their rigor in addressing the questions above, but also by ensuring that the team has enough horsepower to get the job done. While the risks of doing a bad deal are obvious, most JV discussions don’t get over the goal line even where there is substantial value.

For example, only 2 of 12 JV negotiations conducted by a major European company reached closure within a year. Of the remaining 10, 7 would have been very attractive deals that created value – but the horsepower just wasn’t in place to get the deal over the goal line. The problem? Executives who were charged with operating assets, and compensated based on managing production and costs of those assets, were trying to push JV deals through on a “nights and weekends” basis. This isn’t uncommon. Unlike acquisitions where the corporate M&A team drives the work, JV dealmaking is often left to the business units.

In terms of staffing the deal team, better JV dealmakers avoid doing deals on a part-time basis. They also assign a mix of business unit staff and experienced dealmakers to push deals and avoid “throwing the deal over the fence” to a completely different set of people after the signing and celebration.

As Mark Twain once said about medicine: “Be careful when reading health books; you may die of a misprint.” We hope that this article and checklist is helpful – but please view it as a tool rather than a substitute for experience when practicing the art of structuring JVs.

Download the PDF version of this article.

We understand that succeeding in joint ventures and partnerships requires a blend of hard facts and analysis, with an ability to align partners around a common vision and practical solutions that reflect their different interests and constraints. Our team is composed of strategy consultants, transaction attorneys, and investment bankers with significant experience on joint ventures and partnerships – reflecting the unique skillset required to design and evolve these ventures. We also bring an unrivaled database of deal terms and governance practices in joint ventures and partnerships, as well as proprietary standards, which allow us to benchmark transaction structures and existing ventures, and thus better identify and build alignment around gaps and potential solutions. Contact us to learn more about how we can help you.