[Infographic] Independent Perspectives Prove Effective in Resolving JV Disputes

98% of disputes that have been referred to a dispute review board do not proceed to arbitration or litigation.

Techniques to help take complex valuation issues off the table

COMPANIES ROUTINELY FIND themselves in painful JV negotiations, reaching “walk-away points” and failing to close deals because of hard-to-value contributions, differences in key assumptions, or contributions that do not support the desired ownership split or level of control.

It does not have to be this way. Relief lies in a paradox: while JVs often introduce more complex valuation challenges than other transactions, the flexibility inherent in JVs simultaneously offers dealmakers a range of techniques “to take valuation issues off the table” or otherwise help the counterparties get to yes.

The purpose of this article is to explain how the valuation process in JVs should be run – and to outline the most common and best of these deal structuring techniques.

On the surface, JV valuation looks a lot like M&A valuation, only harder. In most M&A and many JV transactions, the parties need to value some existing businesses or determine the worth of specific contributions that have associated revenues or income streams, or have industry “comparables” to provide a benchmark valuation range. To be sure, agreeing on valuation of such contributions can be time-consuming and difficult. The counterparties will often have different assumptions about growth prospects, synergies, liabilities, and risks – not to mention the inherent price tension of any buyer and seller. But, methodologically, the valuation process is well-mapped, with established valuation techniques from which to pick.

With M&A transactions the work stops here.

But most JVs add complexity to the valuation picture. Yes, the companies may plan to contribute to the JV certain existing businesses, product lines, assets, cash, or future capital commitments that lend themselves to traditional valuation. But those contributions are rarely even close to the full list of contributions “going into” the JV – and thus what drives final valuation, ownership split, and economic arrangements.

What makes JV valuation so hard? For starters, most JVs include a range of important contributions that are not bundled into an easy-to-value business with existing cash flows – but, rather, are hard-to-value “pieces” of a business, such as market relationships, capabilities, technologies, proprietary data and processes, skilled people, support services, and privileged assets that do not have an external market price. What’s more, unlike in M&A, the ownership of many of these contributions (e.g., services, technologies, brands) is not transferred to the venture, but, rather, is provided by one partner under some exclusive or otherwise privileged basis to the venture. And, unlike M&A, few situations lend themselves to an auction process – i.e., negotiating with multiple partners in parallel – which in effect creates a market valuation where one may not have existed naturally before.

It is enough to stymie even the most driven dealmaker, and to cause investment bankers to look elsewhere for work.

Consider the negotiation of an industrial equipment JV between a US company that manufactured innovative components and a Middle Eastern player with access to regional customers, low cost utilities, and privileged access to key raw materials. The outline of the JV called for the US company to contribute patented process technology, US legacy manufacturing plants, and US government export approvals. For its part, the Middle Eastern company would contribute regional customer relationships, local corporate facilities, low cost utilities and key materials, import approvals, and initial capital. Since local regulations required the domestic company to hold a majority ownership position in any venture, the parties had agreed that the JV would split ownership 51:49.

Given that the contributions and ownership had been agreed upon, all that was left to do was to value the contributions – and, if the Middle Eastern partner’s contributions did not reach 51 percent of the total contributed value, then agree on a financial true-up to reach it. The valuation exercise quickly got complicated, as the companies’ dealmakers found themselves in positional debates over the worth of inherently hard-to-value contributions, and circular discussions about the future value of the business and each company’s fair share. The senior sponsors felt a large business opportunity starting to slip away because of these valuation issues.

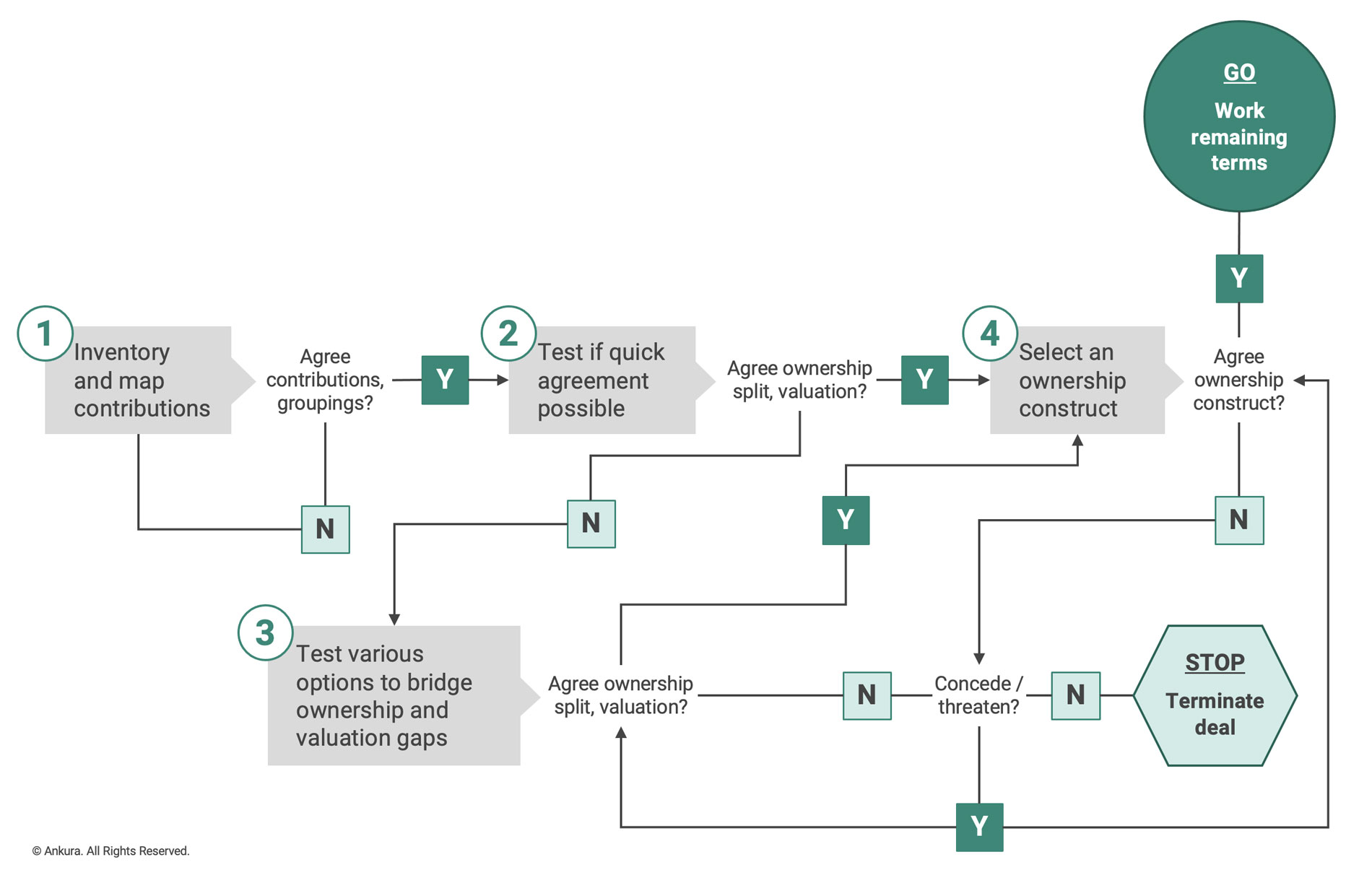

Given these challenges, how should companies approach JV valuation? We suggest companies adopt a four-step approach designed to take complex valuation issues off the table, and ultimately get to a good yes or a quick no (Exhibit 1). That process reduces to four steps: (1) inventory and map contributions; (2) test to determine if an ownership split can be quickly agreed and the valuation of those contributions supports it; (3) if not, test a number of creative techniques to bridge valuation gaps; and, (4) assuming an agreement is reached, select an ownership construct to define how the ownership split will translate into control and economic flows, and move on to discuss the remaining deal terms.

List all contributions from each shareholder required to achieve the business intent

Separate contributions into two categories:

Discuss with counterparty desired ownership split (e.g., acceptable ownership ranges, 50:50 or 51:49 requirement)

Perform first pass valuation focused on easy-to-value contributions (e.g., cash, funding commitments, full businesses with cash flows, inventory)

Determine if the hard-to-value contributions (e.g., brands, relationships, expertise) are “equal enough” – i.e., relatively small, roughly offset

Finalize business case, including size of opportunity (value of contributions will be an input into calculation) to determine if venture at desired ownership split exceeds hurdle rate

Compare value of each party’s ownership impacting contributions to determine if they support the ownership split

Consider different approaches to overcome ownership and valuation gaps:

Choose corporate form (e.g., single JV vs. multiple legal entities; LLC vs. C-Corp)

Structure JV agreement and ancillary agreements (e.g., contribution agreement, service agreements, offtake agreements) to reflect agreed contributions, valuation outcomes, control, economic flows, and any other related terms agreed during this process

Do we agree to the contributions, including which will and will not impact ownership?

Can we agree to an ownership split and that the ownership impacting contributions roughly support it?

Do any of these approaches close the gap, enabling us to agree to an ownership split and valuation?

Can we agree to an ownership construct based on the agreed ownership split?

This process focuses on the negotiation of project, new business, or hybrid JVs – JVs that may include existing businesses, but also new contributions – not consolidation-style JVs. In consolidation-style JVs, such as Morgan Stanley Smith Barney or MillerCoors, the parties are in effect performing a merger at the business unit level. In these cases, the valuation process typically starts with a standalone valuation of each party’s current business, then an estimate of the synergies and whether those synergies will be allocated 50:50 or in proportion to the size of parent companies’ contributed businesses to generate the relative ownership split.

New business or hybrid JVs tend to have more complex valuation issues as some of the contributions have existing cash flows, while others do not. This four-step valuation process is specifically designed to help overcome and simplify these issues.

The first step is to identify and inventory the contributions necessary to deliver on the intent and scope of the proposed joint venture. Once listed, the deal teams should differentiate the nature of each contribution, with the first split separating contributions based on whether they should impact the partner’s equity interest in the venture or not (Exhibit 2).

In general, contributions that impact equity interests are those that are “fully transferred” into the venture, or where access is provided by the partner at no cost or clearly below market rates. Examples include cash, existing businesses and product lines with profit streams, plants and equipment, inventory, revenue bearing contracts, and royalty-free brands, technology, or other intellectual property (IP). Because these contributions impact ownership, they will need to be valued.

Contributions not impacting a partner’s equity interest in the JV are those where legal ownership is retained by the parent company (rather than transferred to the JV), and where the JV will compensate the parent for usage at a market or otherwise fair rate. Examples include parent-provided raw materials, components, technical or administrative services, and technologies that are linked to a purchase contract, service agreement, technology license, or other fee-based agreement. In most cases, people seconded into the JV fall into this category, assuming the JV reimburses the parent company for those employees’ salaries and other costs. Because the parent companies are being compensated for these contributions through other contracts, they do not impact ownership and therefore do not need to be valued for the purposes of supporting the ownership split.

Next, the team should determine which of those contributions impacting ownership are easy- versus hard-to-value. Easy-to-value contributions tend to have defined market values (e.g., cash, raw materials) or existing cash flows (e.g., full profit and loss businesses). Hard-to-value contributions tend to lack defined market benchmark prices and existing cash flows. Typically, they are either intangible assets or tangible assets with long payback horizons, unproven or highly uncertain cash flows, or cash flows that are heavily dependent on the complementary parent company assets placed around them (e.g., know-how, manufacturing plants incorporating unproven technologies).

To help deal teams place potential contributions into different categories, we have developed a simple tool that maps contributions based on two dimensions – impact on ownership shares and degree of valuation difficulty (Exhibit 3). Deal teams can use this as a rough starter guide to determine which contributions might need to be valued, and how much perspiration and creativity will be required in the work.

It is important to note that choices made when addressing ownership and valuation can have significant tax and accounting impacts (e.g., capital gains taxes on contributions, impacts on parent company financial ratios) and will differ by corporate form and jurisdiction. Dealmakers should work with internal or external tax and accounting experts to ensure these issues are taken into account and addressed appropriately.

In the industrial equipment JV, the assets impacting ownership and thus needing to be valued were the US company’s patented process technology, manufacturing plants, export approvals, and future funding commitments and the ME partner’s customer relationships, seed capital, import approvals, and future funding commitments. The contributions not impacting ownership and thus not needing to be valued were the ME company’s low cost utilities, key materials, and corporate facilities because they were to be provided on a contractual basis at market rates. The key materials could have been considered ownership impacting contributions because they were offered at privileged rates, but they were not because it was unclear whether the discount was significantly below market rates.

To remove some of the ownership impacting contributions from the valuation exercise, the dealmakers agreed that the export and import approvals should offset each other, in terms of value. The same was true for the funding commitments as they agreed any future build in the Middle East would be funded in proportion to each party’s ownership stake.

The remaining contributions, aside from the seed capital, were difficult-to-value assets. The process technology was an intangible asset. Its value was extrinsic because it relied entirely on the assets placed around it, making it very difficult to value. The legacy plants and customer relationships were unproven assets. Production volumes, O&M costs, and useful life of the legacy plants were unknown because the process technology had not yet been tested at full production levels. Exacerbating the problem were loosely defined plans to build new plants in the Middle East that would render the legacy US plants obsolete. As for the Middle Eastern partner’s customer relationships, they also could not be accurately valued because the company was unable to lock-in advance sales contracts (i.e., revenue bearing contracts), leaving sales forecasts open to debate.

By the end of step one, inventorying and mapping contributions, the parties should agree on what each partner will be contributing – or at least have a good starting point. This list of contributions should be developed with the goal to best meet the business intent and scope of the venture. If the parties are unable to agree on at least the key contributions, the dealmakers should revisit the basic deal concept and try to develop an alternative deal option before proceeding to step two.

Having identified potential contributions, it is time to discuss the desired ownership split and see if there is an easy answer on valuation. In many JVs, the parties come to the transaction with a target ownership level or range already in mind. The target might be 50:50, reflecting a desire for an equal distribution of risks, rewards, and at least equal control. In other instances, local regulations dictate certain equity floors or ceilings. In India, sectoral caps are placed on foreign partners ownership levels. For example, foreign direct investment in the insurance sector is limited to 26 percent.

Because of this, the process of valuation in JVs is often flipped on its head. Rather than doing a bottom-up valuation of all the contributions and using the resulting answer to “mathematically” generate an ownership split, JV partners often also take a top-down view, “managing” the list of contributions and their valuations to arrive at the target ownership level or range. While that sounds complicated, it often makes it much easier to get a good deal done quickly.

Here is how it works. Consider a theoretical transaction between two companies contemplating a 50:50 JV to develop and commercialize a new technology. Each partner brings to the venture some core IP, strong regulatory and market relationships in different regions of the world, a few existing assets such as an R&D facility and production plants that could be re-purposed for the venture, some early customer contracts, and, most important, capital to invest in the business.

A first-pass attempt to get to agreement on valuation and ownership would work like this: the counterparties take the contributions that are easy-to-value (e.g., capital, existing customer contracts, existing product lines if applicable) and use traditional valuation techniques to arrive at a first-pass valuation on those. Then, the counterparties look at the remaining contributions and ask two questions. Firstly, can some or all of these be “offset” because they are similar enough to other contributions from the partner? For instance, can the partners just agree that their brands, market relationships, or core technology – while admittedly different – are “even enough,” and thus offset? Secondly, and related, are these or other difficult-to-value contributions small enough not to significantly move the ownership split? For instance, the partners might agree that 95 percent of their contributions to the venture come in the form of cash, funding commitments, IP of equal and offsetting value, and a few other items where market values exist – and therefore, other contributions need not be valued and negotiated.

In many situations, that’s sufficient precision to move forward.

Of course, the size and nature of the opportunity will inform how much “short-cutting” of valuation can be done with these approaches. The larger and more important the market opportunity, the more attractive the JV opportunity is relative to the best alternative for the assets in question. The shorter the time-window to move, the more important it is to avoid getting hung up on hard-to-value assets.

If the parties agree they are “close enough” to the target ownership range, then the valuation work is done – and the negotiators’ attention should turn to other deal and launch items.

If the parties cannot agree, then there are a number of options that should be considered to bridge the gaps. These include true-ups, contractualized contributions, scope alterations, creative ownership and economics, other valuation techniques, and offsetting contributions (Exhibit 4). Let’s look at each briefly.

A true-up refers to an extra upfront cash payment made by one partner to the other (or into the venture) designed to re-balance the contribution ledger to reach the desired ownership level. Most often used as a tool to help otherwise-unequal partners achieve 50:50 ownership, true-ups are useful only after the partners have already agreed on what to contribute to the venture, and how to value those contributions.

Another way to resolve valuation issues is for the parent company to provide a contribution on a commercial (i.e., fee) basis, as an alternative to transferring ownership to the venture. For instance, rather than contributing a manufacturing plant, the partner might provide the JV with access to the plant through a long-term lease and maintenance contract. Such contractualized contributions – which may or may not change the nature of the deal in a targeted way – allow companies to take valuation issues off the table, sidestepping disagreements over valuation methodology or underlying assumptions by replacing them with market-based mechanisms.

Another potential solution is scope alteration. By narrowing or broadening the JV’s geographic, product, service, or value chain scope, a problematic contribution might be eliminated from the valuation, made to more closely resemble a full profit and loss business, or configured to offset against a similar contribution from the other party. For example, valuing a parent company’s contributions of IP and manufacturing plants might be difficult, but if the scope was expanded to include the full value chain (i.e., R&D, procurement, supply chain, warehousing, distribution, marketing, and sales) to create a business with cash flows, valuation could become much easier. This is rarely a first resort to bridging ownership and valuation gaps since it will impact the overall deal rationale and business case, but can be an effective substitute to a true-up when the contributions don’t support the desired ownership split or as an alternative to contractualizing contributions when disagreement over the value of contributions exist.

Alternatively, it may be useful to have a second, harder look at offsetting contributions. An initial search for naturally “offsetting” contributions – i.e., similar contributions such as brands or market relationships that each partner is making to the JV that can be deemed to be roughly equal and therefore need not be individually valued – is part of the previous step. It can be fruitful to revisit this technique, to see if it is reasonable to offset other contributions. For example, can the counterparties just agree that while one partner’s local market relationships are very different than the other partner’s technology and manufacturing expertise, that they are “equal enough”? Or can they agree that an R&D facility in Europe is equal enough in value to a manufacturing plant in Asia?

Dealmakers might also consider various creative ownership and economic arrangements to resolve ownership and valuation issues. Typically, creative ownership and economics entail a departure from the standard-form venture agreement, where each company’s level of control and economic flows are directly proportionate to its ownership stake, and are fixed. For instance, rather than aim at a 51:49 deal structure where the governance rights and economic returns are in similar proportion, is it possible to unbundle ownership, control, and economics in order to help the partners get what they want?

Creative deal terms enable dealmakers to make ownership or economic flows contingent on the performance of the venture or certain contributions, assume risks asymmetrically, phase funding, or tailor control beyond what is implied by the ownership split. Take for example, a 51:49 JV for which the parent companies have split board seats, votes, and economic flows evenly through the use of multiple share classes. In addition to de-linking control and economic flows from ownership, they may choose to further tailor the venture’s risk profile through disproportionate risk assumption. The shareholder with the unproven technology could agree, in exchange for a higher valuation, to cover 100 percent of the venture’s losses up to a specified threshold, then, when the venture becomes profitable, it would be reimbursed with a disproportionately large allocation of dividends until it was repaid in full.[1]Additional details on Creative Ownership and Economic Arrangements will be covered in Part II of this article. See, The Joint Venture Exchange, July, 2012, forthcoming)

Another way to resolve valuation differences is to use other valuation techniques (Exhibit 5). Many traditional and creative valuation techniques have been developed to handle hard-to-value assets and businesses. For example, methodologies such as expected monetary value (EMV) build on traditional approaches such as discounted cash flow (DCF) to better handle multiple scenarios and option value, and therefore can be useful when the parties have different time horizons and risk tolerances. The relative allocation approach is another effective method, though it can be time consuming and complicated to implement. Here, dealmakers estimate the relative value of segments of the value chain, calculate the value of a few specific segments based on market data, then extrapolate to the other segments. This approach is most effective when one party is providing all of the contributions for a given value chain segment.

When dealmakers are stuck valuing IP, capitalizing royalty rates may get them over the hump, but agreeing to the capitalization period is usually tricky. A longer period will imply a greater value and shift risk from the shareholder contributing the IP to the venture. Other less traditional approaches may be used as a sanity check or second opinion to test the outputs of the more traditional approaches. Some of these techniques include factoring an asset’s performance relative to benchmarks or capitalizing run rate costs for differentiated capabilities.

From a problem-solving approach, it can be useful to start with the nature of the valuation problem, and then work through a set of prompts organized in an issue tree to determine which techniques to consider and in what sequence (Exhibit 6). For example, if the valuation problem is that the initial valuation does not support the target ownership split, then the counterparties might consider a true-up payment. If that is not feasible, then they might look at contractualizing certain contributions.

After testing these options to bridge ownership and valuation gaps, if the parties are still stuck, then they should revisit the size of the opportunity relative to their alternatives and their counterparty’s alternatives and determine whether to concede, threaten, or simply walk-away. But, before doing the latter, the dealmakers should ask themselves, “Am I ready to walk-away from this deal over the differences in valuation?”

It was in this step that the industrial equipment JV transaction appeared ready to break down. The parties became fixated on the value of the process technology and legacy plants, and the negotiations devolved into a multi-variable debate of the relative value of the technology, legacy plants, and customer relationships to determine the out-of-pocket cash with which the ME company would seed the JV. The US company valued its technology and plants as an end-to-end business that would produce significant cash flows for the venture, particularly in the short-term as the ME plants were being built. The counterparty viewed the plants as a liability. They were old, highly depreciated assets that were poorly situated. The counterparty considered these assets to be worth their depreciated book value – arguing the replacement cost was not relevant given the undesirable location. Further concerning the ME company was that full production volume and cost information for the legacy plants with the new technology was unavailable. They also discounted the value of producing units for the 2 to 4 years it would take to build plants in the Middle East, given its long investment horizon.

Fortunately, the dealmakers revisited the overall economics of the opportunity and realized losing the deal over these swings in valuation was not worth it. The parties elevated the conversation and focused on how much seed capital was needed to fund a successful venture. Once they aligned on that very practical issue, then the parties simply agreed that the US company’s technology and plants, along with a few pre-defined contingent payments for the near-term performance of their legacy plants, offset the Middle Eastern company’s contributions of customer relationships and seed capital, enabling them to close a good deal for both companies – a deal that could have been lost as the parties squabbled over the value of difficult-to-value contributions.

If the parties are able to ultimately agree on ownership and valuation, then the last step is to select an ownership construct and agree to the value-sharing terms. This requires choosing a corporate form (e.g., single JV vs. multiple legal entities, LLC vs. C-Corp) and how control and economic flows will relate to the ownership split. If the parties can’t agree on this step, they are left once again with the option to concede, threaten, or walk-away. Assuming the parties reach agreement, they should work the remaining deal terms and structure the ancillary agreements, capturing agreed contributions, valuation outcomes, governance rights, economic flows, and other related terms.

Before walking away from a promising JV because of hard-to-value contributions, consider whether the value created by the deal warrants using a creative approach to valuation. While Albert Einstein may have not have structured many JVs, he may have said it best: “Everything that can be counted does not necessarily count; everything that counts cannot necessarily be counted.”

We understand that succeeding in joint ventures and partnerships requires a blend of hard facts and analysis, with an ability to align partners around a common vision and practical solutions that reflect their different interests and constraints. Our team is composed of strategy consultants, transaction attorneys, and investment bankers with significant experience on joint ventures and partnerships – reflecting the unique skillset required to design and evolve these ventures. We also bring an unrivaled database of deal terms and governance practices in joint ventures and partnerships, as well as proprietary standards, which allow us to benchmark transaction structures and existing ventures, and thus better identify and build alignment around gaps and potential solutions. Contact us to learn more about how we can help you.

Comments