JANUARY 2022 — There was a time when partnerships by Saudi Arabian companies conformed to a predictable pattern. Scoped narrowly, restricted to serving the domestic market, limited to select sectors, and relying on foreign technology and brands, they were no different from the partnerships in other newly liberalized emerging economies.

But this pattern has started to shift.

The world’s increasing thirst for low carbon energy has been nudging the Kingdom towards economic diversification. Vision 2030 gave it a powerful and supportive push.

“Partnerships” are referenced more than 20 times in Vision 2030.

Vision 2030 is both a statement of ambitious economic development goals and a testament to partnerships as a critical enabler of that ambition. It references partnerships more than 20 times over its 85 pages. Backed by Vision 2030, the Kingdom has deliberately encouraged partnerships, including through regulatory reforms and specially created entities mandated to invest in key sectors.

This in turn has transformed the very nature of partnerships by Saudi Arabian companies, and has taken recent partnership activity to levels of pace, scale, and intensity unprecedented in our historical experience serving clients in the Kingdom.

Enter your information to view the rest of this post.

"*" indicates required fields

What is Different?

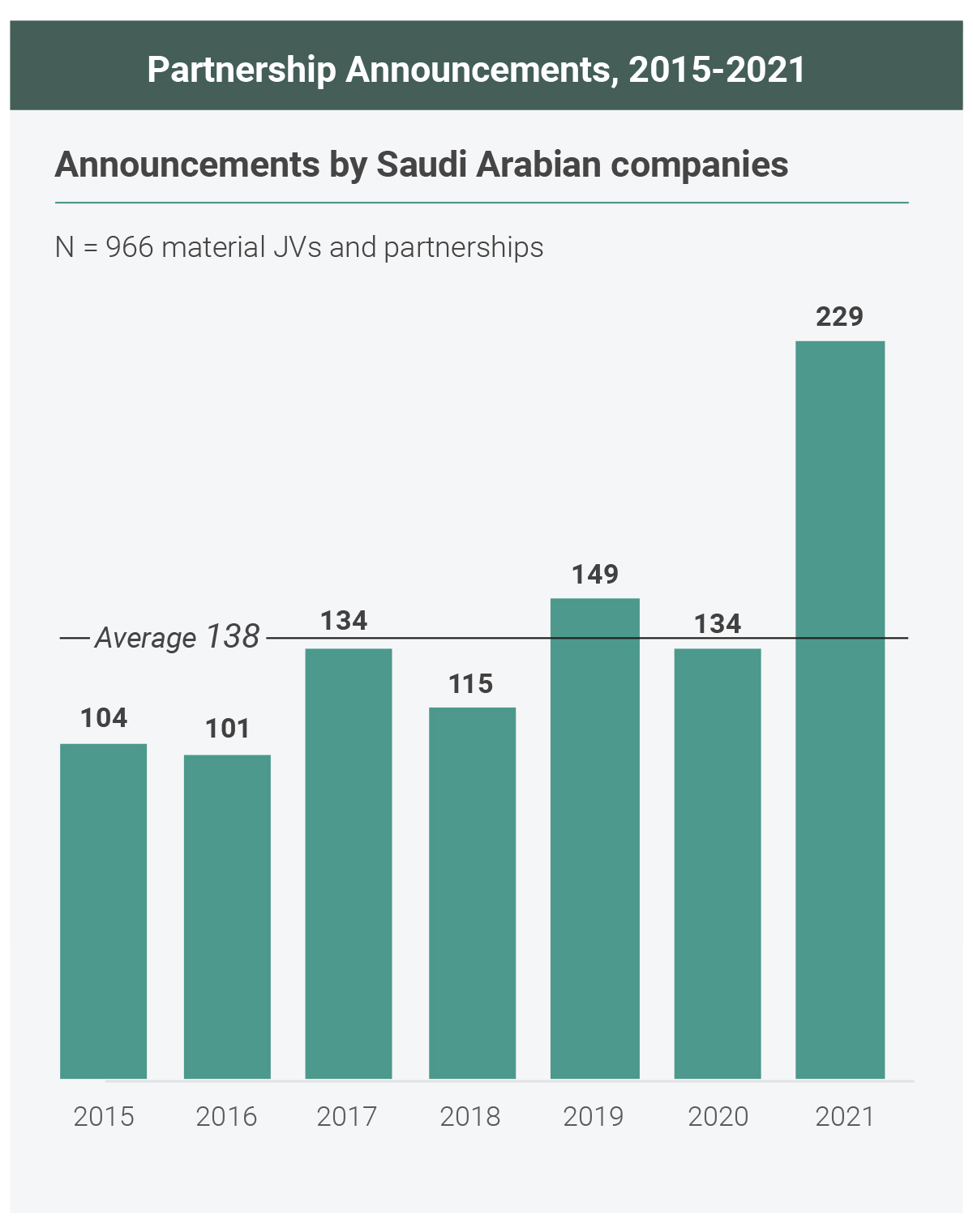

Saudi companies have averaged 138 new partnerships per year in our data set, with new partnership dealvolumes dipping slightly in 2020 before rapidly accelerating in 2021 on the backs of the COVID crisis to reach record highs (Exhibit 1).[1]According to Ankura’s Joint Venture Index, global partnership dealvolumes for 2021 have also risen to record levels – see “Ankura Joint Venture Index – Third Quarter,” November 2021

But equally important is the change in the breadth of these partnerships. In recent years, partnerships by Saudi Arabian companies have broadened their product, market, and value chain scope; are increasingly designed for international expansion; and are more likely to be scattered across sectors beyond oil and gas.

Broader Scope

A number of recent partnerships in Saudi are scoped to cater to the entire region, or to include in-country R&D in addition to manufacturing and sales. For example, Saudi Arabian Military Industries’ (SAMI) joint venture with CMI Defence to develop multifunctional turret systems for armored vehicles includes in-country research, prototyping, and production, while Saudi Advanced Technologies established a joint venture with WISeKey to provide cybersecurity, Internet of Things (IoT), and blockchain services for the entire Middle Eastern market.

Broader scopes are not just the purview of new partnerships, but existing partnerships too, which are being restructured to loosen their constraints and enable growth. Consider Argas, the seismic solutions joint venture between CGG and TAQA that underwent multiple expansions. It was originally scoped for the domestic market, and subsequently rescoped to cover all Gulf countries. A recent restructuring allows it to expand into broader international markets, with the partners agreeing to waive all territorial, technical, and commercial exclusivities and other contractual restrictions previously in place. Similarly, The Olayan Group expanded its six decades-long partnership with U.S .engine manufacturer Cummins through the formation of a joint venture, Cummins Arabia. The venture consolidated the distribution of Cummins’ products across three – Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Kuwait – into a single entity. Under the earlier partnership, The Olayan Group was Cummins’ distributor within the Kingdom, while Cummins distributed its own products in the UAE and used a third-party distributor for Kuwait.

International Expansion

Saudi Arabian companies are using partnerships as a platform to springboard into international markets in many different ways. Oil company Saudi Aramco has multiple partnerships to enable the commercialization of its internally developed technologies – including a partnership with CB&I and Chevron Lummus to scale-up and commercialize its thermal crude to chemicals technology, and another with TechnipFMC and Axens for its catalytic crude-to-chemicals technology. SABIC, the chemical company now majority-owned by Saudi Aramco, has partnerships with DSM, Unilever, Fibertex, Beiersdorf, and UPM among others through which the company is globally commercializing its suite of circular materials and technologies encompassing circular polymers, bio-based renewable polymers and the like.

International technology commercialization partnerships are but one way companies are venturing outside the Kingdom. Another is through partnerships to build domestic capabilities that can then be utilized to serve international markets. Technology company TAQNIA’s joint venture with Skyware and Crescent, collaborating with King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology (KACST), aims to become a provider of advanced services and solutions to satellite operators globally. Shipping carrier Bahri and Saudi Aramco’s joint venture with Lamprell and Hyundai Heavy, International Maritime Industries (IMI), is intended to position Saudi Arabia as a regional hub for maritime products and services.

Saudi companies are also pursuing direct investments and partnerships abroad. In general, these are still tentative – and involve minority and passive stakes, non-controlled joint ventures, or non-equity partnerships. But there are a few exceptions involving larger commitments, such as SABIC’s joint venture with Exxon Mobil that is building a world-scale steam cracker and derivative units along the US Gulf Coast. Similarly, the Kingdom’s Public Investment Fund (PIF) has several large and high-profile international investments, like its multi-billion dollar partnership with SoftBank that is making targeted investments in technology companies internationally. The Fund is also using its international investments to develop capabilities within the Kingdom. It acquired a stake in Korean steel producer POSCO’s engineering and construction division, which involved a commitment to establish a PIF-controlled joint venture in Saudi Arabia that would execute on local projects, and through which POSCO would share relevant technology.

Sector Diversification

Upstream oil and gas accounted for less than 5% of the partnerships in our data set, overshadowed by the high-volume partnering activity in financial, technology and communications, industrial, power and utility, and other sectors. Companies in these sectors are engaging in partnerships to advance existing capabilities towards digitalization, sustainability, or convergence with global standards. Take Saudi Telecom Company (STC). The company’s digital payments subsidiary, STC Pay, has an alliance with Western Union under which the latter provides all underlying settlement, collection and distribution services and has a minority equity investment in STC Pay. STC additionally has partnerships with the likes of Nokia, Ericsson and Huawei in 5G, cloud computing, and computer security projects. Similarly, Saudi Railway Company (SAR) has a partnership with Huawei for joint innovations in smart railways, comprising the application of IoT, artificial intelligence, cloud services and 5G across SAR’s railway network.

ACWA Power, a company partially-owned by PIF, is at the forefront of the sustainability push. It has several partnerships in the region and beyond to build and operate large clean energy projects. It recently signed a joint venture with Air Products and the city of NEOM to build a $5 billion green hydrogen-based ammonia production facility in the Kingdom. Sustainability-centered partnerships have made their mark in other industries too. Mining company Ma’aden has an alliance with Drosrite in waste management, while Saudi Aramco is exploring partnerships with Shell and AMG in catalyst recycling, and with Repsol to produce synthetic fuel using green hydrogen and refinery-emitted carbon dioxide.

What Does This Imply?

Companies in the Kingdom now include among their ranks some of the most prolific dealmakers in the world (Exhibit 2). This deal-making is both increasing the sheer number of partnerships in company portfolios and driving considerable diversity and complexity into the mix.

How should companies in the Kingdom position themselves for excellence in deal-making and in post-deal governance and management? The answer varies for different categories of companies.

Large Companies

Saudi Aramco, SABIC, and Saudi Telecom Company have each established dozens of recent partnerships. Other large companies in the KSA have been partnering vigorously too. SAMI, Saudi Electricity Company, and TAQNIA have entered into more than ten partnerships each over the same period. Not only have the partnership portfolios of these companies swelled, but their portfolios now carry an assorted mix of partnerships. Saudi Aramco’s partnerships span chemicals and services in typically large deals, and numerous smaller partnerships in digitalization and sustainability. Each of SAMI’s partnerships is for a different product or technology, and has its own localization targets and commitments for technology transfer and supply chain development. Saudi Telecom Company’s partnerships cover traditional infrastructure pooling and upgrades, and non-traditional digital payments, IoT and cloud platforms. In addition to the volumes and variations in size and scope, the portfolios of these companies have a number of partnerships that are effectively non-operated.

Partnership portfolios that are large, complex, and involve material non-operating positions demand deliberate attention. Left to providence, or worse still, subject to ad hoc oversight with limited coordination, these portfolios tend to mask embedded risks as well as opportunities.

Global companies like ExxonMobil, Shell, Dow, Microsoft, and BHP with similarly challenging partnership portfolios have invested in structures, processes, and policies to manage their partnerships, find ways to improve oversight discipline, and capture synergies. Dow has a robust system of corporate controls for joint ventures that it exercises through its Board Audit Committee and corporate structures such as a JV Governance Board and an M&A Technology Center. For instance, every material joint venture goes through a rigorous corporate level review every two to three years, where senior management challenge its performance, and revisit its strategic rationale, trajectory, and future options.[2]“Are your JVs a Ticking Time Bomb?,” The Joint Venture Exchange, June 2009 BHP, in its mining business, created a new executive role (Asset President of Non-Operated Joint Ventures) and a dedicated team to better manage risk and value in its non-operated ventures.

While not all large companies in the KSA have begun to think systematically or strategically about their partnership portfolios, there are some notable exceptions. SABIC has a JV Affairs Unit tasked with safeguarding SABIC’s corporate interests in new and existing joint ventures,[3]“Governing a Portfolio of Joint Ventures: How Do You Measure Up?,” The Joint Venture Exchange, December 2020 while Saudi Aramco is creating organizational units for governance and business support to important joint venture categories (such as domestic downstream JVs, drilling and workover JVs), and an integrated corporate development organization to optimize its portfolio.

Investment Vehicles

PIF, and to a lesser extent Kingdom Holdings and similar investment vehicles, have been partnering rapidly across sectors and geographies. PIF itself had more than recent 25 partnership announcements, not including voluminous new partnerships executed through its controlled portfolio companies. When companies partner at breakneck speed the perils are twofold. First, the dealmaking process tends to get short-changed, with insufficient resources and creativity expended in building a business case, screening potential partners, testing alternative deal constructs, and planning for launch – potentially leading to partnerships that are handicapped from the start and have a higher probability of failure. Second, and more subtle, is an excessive focus on feeding the deal pipeline and negotiating deals, at the expense of managing the resulting partnerships across their lifecycle.

Investment vehicles in other regions, like Abu Dhabi’s Mubadala and Singapore’s Temasek, have a longer track record in building global partnership portfolios – and correspondingly, in trying to balance deal-making excellence, with post-deal governance and management. Their approach can offer valuable lessons.

In Mubadala Investment Company (MIC), for instance, the investment process is set out in a rolling five-year business plan and refined in the annual budget. MIC’s Investment Committee comprised of the MIC CEO, business unit CEOs and other senior executives reviews investment proposals using a standard framework that assesses the investment’s impact on key metrics at the portfolio level, in addition to criteria like minimum financial return and fit with current mandate. Once the investment is approved and made, MIC’s degree of ongoing involvement depends on the nature of the investment. At a minimum, each business unit monitors and reports to the Investment Committee if approved parameters change significantly, further investment becomes necessary, or an exit is considered. This ongoing involvement extends to MIC’s joint ventures, where monitoring and approvals are executed through MIC’s representatives on the Board. MIC’s representatives on joint venture Boards function under detailed delegations of authority laying out the matters they can approve, and those that are required to be presented to the Investment Committee for approval. MIC has developed a Corporate Governance Handbook for its Board representatives on joint ventures, which sets out their roles, responsibilities and fiduciary duties. Further, MIC’s Chief Legal Officer oversees a corporate governance training program for Board representatives. MIC also monitors the performance of its Board representatives through a detailed evaluation process.[4]Mubadala Base Prospectus, 2018

Family-Owned Businesses

The Olayan Group, Abdul Latif Jameel, E.A. Juffali & Brothers, and other family-owned businesses have a storied history of partnering. Sealed by a handshake, and sustained by the business acumen and relationships built by the first-generation, their partnerships have tended to cover familiar terrain – master franchises, exclusive distributorships, joint manufacturing arrangements, and the like. Many of these partnerships have lasted over decades and are extraordinarily successful. Abdul Latif Jameel’s partnership with Toyota, as Toyota’s distributor in the KSA, started in 1955 and has since evolved to include Toyota distributorships globally – including in Algeria, China, UK, and even Japan.

But these family-owned businesses are transitioning into their second and third generations – with more exposure to international standards of corporate governance. This, coupled with the emergence of newer deal-intensive sectors, more competition for deals, and novel deal constructs, has prompted many family-owned businesses to ask themselves: How can we professionalize the dealmaking process and post-deal governance and management?

Professionalize should not be confused with formalize, or erroneously taken to mean the replacement of family-members in favor of outsiders. Nothing can be further from the truth. The indiscriminate introduction of systems, processes, and structures that neither reflect the family’s values, nor incorporate elements of what has worked in the past, nor accommodate the treasure trove of experience and business instinct of the founders and their descendants can unleash more harm than good.

Instead, family-owned businesses should simply direct their efforts to these actions:

- Build a strategic framework for partnering – understand where the business is headed, and the role of partnerships within that strategy

- Define (and respect) the roles and decision-making authorities of family members with respect to partnerships

- Rely on professional business development teams (including family members and outside hires) to source, screen, negotiate, and review partnerships

- Outline the decision-making process for recurring decisions like budgets and capital expenditures, especially if decisions require the endorsement of family members outside of formal approvals

- Articulate the core values of the business and family and how they are expected to apply to partnerships, and make sure effective internal controls are in place against non-compliance

While companies do their bit in pursuing excellence in deal-making and in post-deal governance and management, regulators too need to play a facilitating role.

Our experience serving clients in economies like India and China shows that deal-making and the resulting partnerships thrive when: i) regulators are transparent; (ii) laws are targeted at specific sectors, deal types, or desired outcomes; (iii) administrative procedures are efficient; and (iv) administrative decisions are consistent. While legislation in the KSA has been radically reformed and modernized of late to assist local businesses and attract foreign investors, the ongoing role of regulators cannot be understated. For instance, the Saudi Arabian Capital Market Authority (CMA), in cooperation with the Ministry of Commerce, has recently published a new draft company law and opened it to public opinion. The CMA should view this an opportunity to determine whether any of the proposed revisions (or existing provisions) in areas such as corporate form, Board size, director liability, shareholder rights, debt issuance and exit have unintended consequences for joint ventures, and accordingly modify them, or clarify their application to joint ventures.

Vision 2030 has propelled Saudi Arabian companies onto a new partnership trajectory – one with unprecedented aspirations, speed, and demands. Now is the time to put in place the policies, practices, and structures for manageability and success, as the path ahead is only upward and onward.

Related Resources

Companies in the KSA have access to events organized by Ankura, and Ankura’s proprietary benchmarks and best-practices. Please contact geoff.walker@ankura.com for additional information.

Events

- Quarterly Saudi Arabia JV and Partnership Forum that brings together executives from leading companies in the Kingdom

- Industry or issue-specific roundtables attended by executives from companies across the world

Benchmarks

- Global benchmarking data and analysis on deal terms, governance and performance, and portfolio management

Best-practices Repository

- Case studies, toolkits and checklists, legal agreements library

- Best-practices in structuring deals / deal-terms, governance, and portfolio management