[Infographic] Independent Perspectives Prove Effective in Resolving JV Disputes

98% of disputes that have been referred to a dispute review board do not proceed to arbitration or litigation.

Practical guidance on structuring a critical provision in a JV agreement

MARCH 2022 — When certain things go awry in a joint venture, non-offending partners typically have the right to exit. For example, if one partner materially breaches the legal agreements, becomes subject to sanctions, files for bankruptcy, or undergoes a change of control, the other partners generally have the right to sell their interests or buy out the offending partner. These terms are often not heavily negotiated.

"*" indicates required fields

A more complicated, and often hotly negotiated, question is: Should any partner have the right to exit the venture “at will” – that is, in the absence of a negative event caused by another partner or a failure of the JV to obtain or renew a material permit, license, or government authorization? For instance, a partner may want to exit if the venture no longer fits its strategy, if it wants to monetize its investment, or if it is misaligned with the other partners on the direction of the venture. While the right of a company to freely exit from an investment seems reasonable, it can be problematic in joint ventures. After all, joint ventures are not just financial investments. Rather, they typically combine distinctive and complementary technologies, know-how, and assets of the partners. Therefore, one partner exiting the venture may threaten the viability of the business or, at a minimum, may be impossible to fully replace. If a partner secures such an at-will exit right, should there be any restrictions on those rights such as a condition that it not exit for an initial lock-up period or a limitation on who the exiting partner might sell to?

To help companies think through at-will exits, we recently analyzed the exit provisions in the legal agreements of 81 joint ventures. Summary perspectives and key findings of this analysis and practical guidance for structuring at-will exits are offered below.

The median lifespan of a joint venture is 10 years – a time frame that has remained largely unchanged for decades. Most joint ventures terminate with one partner buying out the other partners. For example, Russian internet and ride-hail giant Yandex recently declared it was acquiring Uber’s stakes in their food-tech, delivery, and self-driving joint ventures and had secured a $2 billion call option to buyout Uber from their ride-hailing and car-sharing JV. Other JVs end with a full sale to a third-party, dissolution, public listing, or spinoff. For example, the joint venture between Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway, and JP Morgan Chase that promised to revolutionize U.S. healthcare recently dissolved quietly three years after formation.

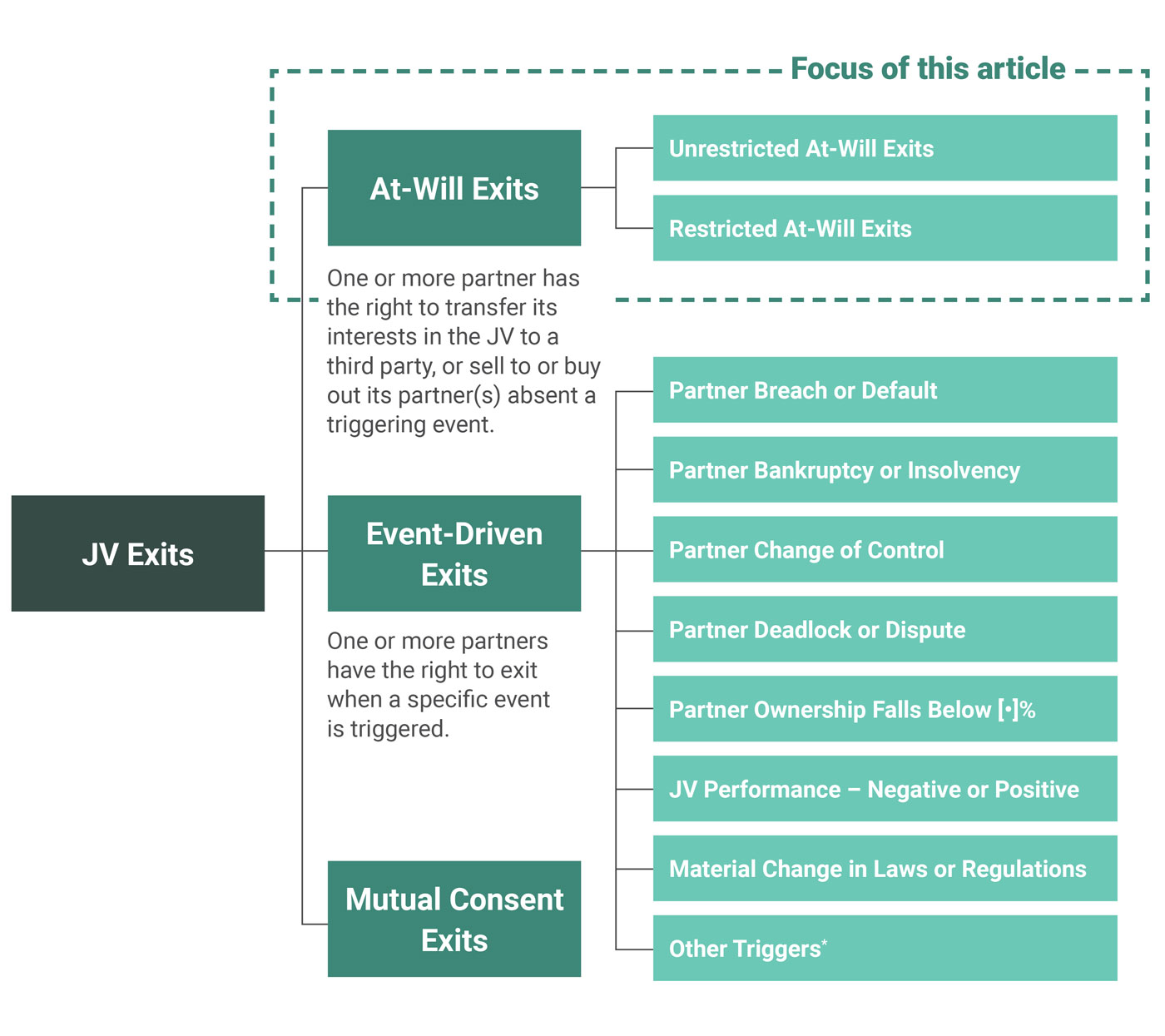

Exit provisions in joint venture agreements fall into three broad categories: (1) at-will or non-triggered exits, (2) event-driven or triggered exits, and (3) mutual-consent exits (Exhibit 1). In practice, most joint venture exits are “negotiated” off-ramps that do not mechanically follow the established legal terms, and nothing stops the parties from negotiating exit terms entirely different from those defined in the agreements. That said, the legal agreements establish the boundary conditions and a starting point for the parties to commence exit discussions. Similarly, well-structured exit provisions provide incentives for partners to resolve disputes by making it more difficult to exit. Negotiating exit rights is important to ensure a company is well positioned in these negotiations. This is especially important for companies that are not “natural buyers” of the venture, hold a minority interest, or are in bed with a counterparty that is state-owned or otherwise wields substantial indirect influence.[1]For additional discussion on JV exit strategies and contractual terms, please see, “Joint Venture Exits: Five Steps to Structuring Robust JV Exit Terms”, Tracy Branding Pyle, Edgar Elliott, and … Continue reading

* Other event-driven triggers include: (i) JV becomes subject to sanctions; (ii) partner underperformance; (iii) partner or JV fails to obtain required consents or permits; (iv) partner or JV license or trademark expires or is cancelled; (v) partner supply or purchase agreement expires or is cancelled; (vi) force majeure / catastrophic event; and (vii) JV term expires

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

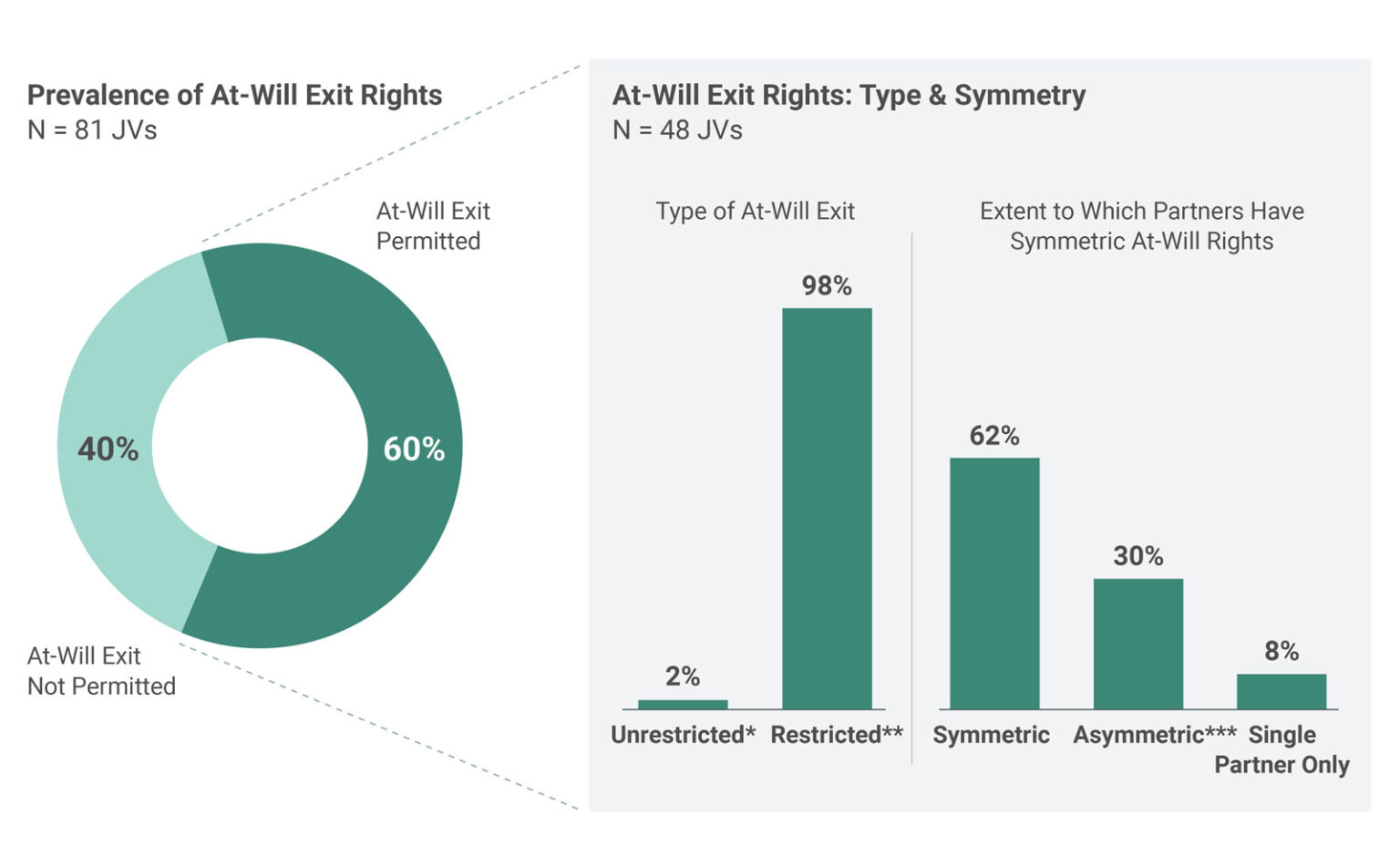

Our analysis of the legal agreements of 81 large joint ventures across industries and geographies shows that 60% give one or more partners the right to exit the venture at will (Exhibit 2). This means that a partner can either transfer its interests to a third party, sell to another partner, or buy out its partner when it pleases, though it may be required to abide by particular conditions or have additional rights such as the right to drag along the partners in a sale to a third party. Of these permitted at-will exits, only 2% were truly unrestricted, meaning the partner could sell any amount of its interests to any third party at any time, without any right or involvement from the current partners such as through a right of first refusal (ROFR), right of first offer (ROFO), or right to tag along.

*Partner is able to transfer any amount of its interests in the JV to any party at any time without the remaining partner(s) having a right to intervene (e.g., through a ROFR, ROFO, etc.).

**Restrictions may be related to (a) a partner’s right to intervene in the exit such as through a ROFR or ROFO, or (b) other limitations such as limits on who can purchase the exiting partner’s interests or conditions such as those relating to when and how much of its interest the exiting partner can transfer.

***At-will exit provisions exist for all parties with different rights for each party (e.g., ROFR, ROFO, drag-along, tag-along).

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

There is also the matter of symmetry. Of the ventures we analyzed, in 92% of those with at-will exit provisions, all partners have some rights to a voluntary exit. But in almost one-third of the agreements with at-will exit provisions, the partners have asymmetric exit rights. For example, in a European renewable energy JV, the partner providing the technical and operational expertise can exit at will subject to the other partner’s right to tag along. Meanwhile, the other partner can exit at will subject to the technical partner’s right of first offer. In 8% of agreements, only one party has the right to exit at will.

When the partners’ exit rights are asymmetric, this is typically linked to lopsided ownership interests or disproportionate operating contributions. For example, in the JV between Clorox (80%) and Procter & Gamble (P&G) (20%) to develop and manufacture household products under the Glad brand, in which Clorox’s existing Glad brand is paired with P&G’s research and development abilities, only majority owner Clorox can sell at will to a third party. However, if Clorox exercises this right, P&G has the right to tag along by also selling its interests to the buyer. This arrangement may reflect Clorox had significant leverage at the time the deal was entered into and wanted the option to sell its Glad brand and related manufacturing equipment and other assets, which it had recently acquired and could be easily carved out from the rest of Clorox’s business.

When structuring at-will exit clauses, companies will need to consider two types of contractual provisions. First are the overall partner rights and obligations that define the overarching process and structure for at-will exit, including the presence and design of ROFRs, ROFOs, tag-along rights, drag-along rights, puts, and calls. Second are limitations on how the exiting partner can execute the exit, including lock-up periods and restrictions on who can purchase its interests in the JV.

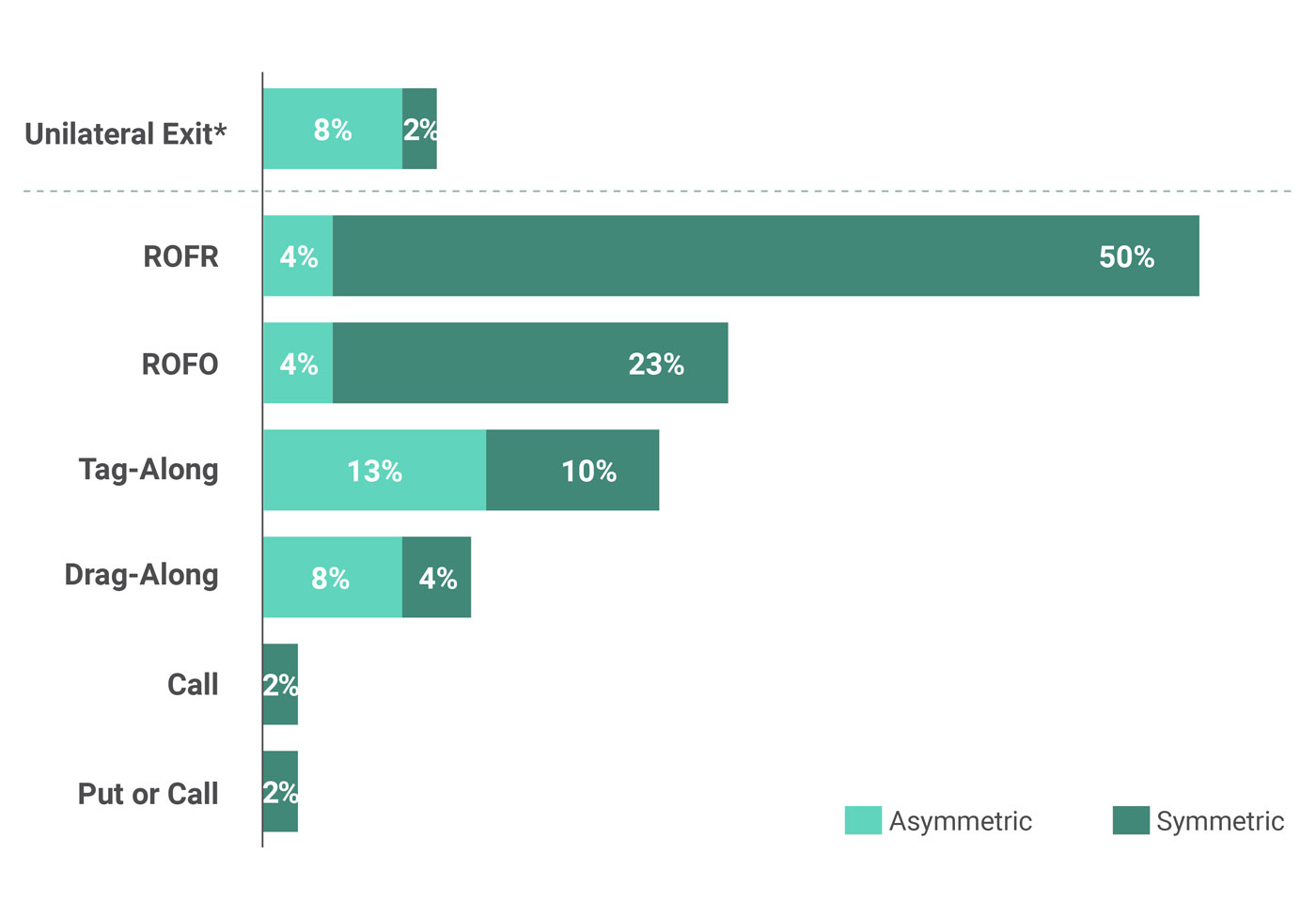

When negotiating at-will exit terms, companies will need to determine which exit rights and obligations are appropriate for themselves and for their partners. Most exit mechanisms favor the party not looking to exit and include a right of first refusal (ROFR), right of first offer (ROFO), and a right to tag along in a sale. Other mechanisms favor the initiating partner. They may include the right to transfer ownership without any restrictions, as well as drag-along, put, or call rights that compel the non-initiating partners also to sell their interests in the venture. Below we explore when some of these rights and obligations may be appropriate as well as how prevalent they are in practice (Exhibit 3).

*Precludes any partner involvement in exit (i.e., no ROFR, ROFO, tag-along, drag-along, put or call mechanisms)

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

The simplest form of at-will exit is when a partner can sell to a third party without any involvement from the other partners. This right is rarely seen in our dataset, occurring in only 6% of agreements. As mentioned above, only 2% of at-will exits are fully unrestricted, whereas the other 4% of unilateral exits are subject to some restrictions, such as a lock-up period, limitations on who the company can sell to, or the need to sell the company’s ownership stake in its entirety. In all but one agreement, the right was one-sided, with only one partner having the unilateral right to walk away. When an agreement included this unilateral right to exit for a single partner, it was when the partner had a significant controlling stake or was a state-owned company or local firm with strong ties to the government. For example, in a JV between a local partner and global player, the local partner had a unilateral right to exit while the global player could only transfer its interests to the local partner.

A right of first refusal (ROFR) is the most common at-will exit provision, seen in over 50% of JV agreements that define at-will exits. It requires a partner negotiating a sale of its stake to a third party to give the other partners a chance to review and match the terms offered by that third party.

ROFRs have advantages and disadvantages for the non-initiating partners holding the ROFR. ROFRs provide such partners an unimpeded opportunity to buy out the exiting partner’s stake without the risk their offer will be rejected. On the other hand, the non-initiating partners do not have the opportunity to negotiate a fit-for-purpose deal as the contractual terms will be those the exiting partner agreed to with a third party with the ROFR a one-time, take-it-or-leave-it offer to the remaining partners. ROFRs may not be attractive to partners that do not have the capital available to buy out their partner or are otherwise not the natural buyer of the venture.

For the initiating partner, a ROFR may have more disadvantages than advantages. A ROFR is not attractive to a potential third-party buyer, given the buyer knows it may have the rug pulled out from under it by a non-initiating party exercising its ROFR. Likely for this reason, ROFRs are rarely found in tandem with any other sorts of exit provisions such as tag-along rights. Both ROFRs and tag-along rights are unattractive to buyers and, in combination, they would be likely to turn away all potential buyers.

When is a ROFR appropriate to include in a JV agreement, particularly for a JV among strategic partners? We commonly see ROFRs in agreements where one party is a natural buyer. For example, the JV is operated by that partner, the intent is for the JV to be 100% owned by a specific partner over time, or the JV is a critical part of the partner’s value chain and thus such partner is unlikely to cede control or exit. Consider a 60:40 Middle Eastern aerospace and defense JV between a local government-affiliated company that held a ROFR and a large international firm. It was always the intention the JV would transition to becoming a wholly-owned subsidiary of the local company, having benefited from the experience and technical know-how of the international partner. The ROFR would therefore facilitate the government-affiliated partner’s ability to purchase the international partner’s 40% stake when it decided to exit. Despite the fact that a ROFR tends to favor the natural buyer or long-haul partner in a JV, we also see ROFRs when there is not a clear natural buyer. Furthermore, we see that in an overwhelming 92% of cases ROFRs are granted to all partners.

The second most prevalent at-will exit mechanism is the right of first offer (ROFO), which was found in 27% of JV agreements reviewed. Unlike the ROFR, which gives the non-initiating party a right to buy the interests after the initiating partner negotiates with a third-party buyer, a ROFO requires a partner wishing to exit to provide notice of its intentions and give the other partners an opportunity to offer to buy its interests before entering into a negotiation with a third-party buyer. ROFOs can be structured in different ways. In some cases, the initiating partner proposes a price for its interest and the non-initiating partner can elect to buy at such price; if it does not, the initiating partner has a set period to find a third-party buyer at or above an agreed floor price (typically to the offered price, but in some cases different – e.g., 95% of the offered price). In other cases, the initiating partner notifies its partners of its desires to sell and the non-initiating partners can then make offers to purchase the interests; the non-initiating partner can accept such offers, or, it can sell to a third-party buyer at a price above the highest price offered.

From the right holder’s perspective, a ROFO is weaker than a ROFR. A ROFR guarantees the non-initiating party the right to buy the interest while a ROFO does not since the initiating party could reject the non-initiating party’s offer. On the other hand, the current parties determine the terms and conditions themselves, which gives the non-initiating party an ability to create a more fit-for-purpose deal than just accepting the terms of a deal hashed out with a third party.

From the initiating party’s perspective, a ROFO has some advantages. It can accelerate the exit process by preventing the initiating partner from negotiating first with a third party and then the partner with the ROFR (In practice, the exiting partner may approach the partner with the ROFR before or simultaneously with the third party). Such third-party negotiations can be time intensive and require significant diligence and discussion. Furthermore, a ROFO ensures that when the initiating partner approaches a potential third-party buyer, the interests it is selling are unencumbered by a ROFR contingency, thus making the interests more attractive to potential buyers.

Parties envisioning being in the JV for the long haul, and therefore more likely to be the non-initiating partner in an at-will exit scenario, might want to think about including a ROFO in their JV agreement if their partners find a ROFR unpalatable. In our experience, ROFOs often end up in JV agreements as the result of a compromise among the partners after a ROFR is deemed unacceptable. ROFOs are largely a symmetrical right with all partners, rather than a subset of partners, being given a ROFO in 85% of cases where ROFOs are seen. Just like a ROFR, a ROFO provides little comfort to a non-initiating party with no financial wherewithal to buy its partner’s shares. However, the data reveal that ROFOs are seen in tandem with tag-along provisions in 50% of cases, giving the non-initiating party an opportunity to jump ship if they cannot afford to buy their partner’s shares but do not want to be involved in the JV if a new partner is onboard.

A tag-along right is the right to force the buyer of a partner’s interests to also purchase the interests of the partners with the tag-along right. This right is usually held by minority partners in situations where a majority partner is exiting the venture and, therefore, this right, unlike a ROFR or ROFO, is typically an asymmetric one.

The logic behind a tag-along right is simple: Ultimately, a company enters a venture with partners of its choosing, not a third party. If the company wants to avoid being stuck in a JV with partners it did not pick, then a tag-along provision is a valuable right. In ventures where one partner is a minority or non-operating partner, a tag-along right may be especially germane. A non-operating partner may wish to have a tag-along right, which it would exercise if it did not have confidence of the new buyer to operate the JV as effectively. Similarly, a minority partner may see a tag-along right as an opportunity to monetize its investment.

Our analysis shows tag-along provisions in 23% of agreements in which exiting at will is permitted. Counter to the benefit a tag-along clause brings a minority partner, these clauses can be challenging for majority partner sellers and potential third-party buyers. Neither the seller nor buyer will know if the buyer is purchasing just the majority partner’s share or if such a sale would also require the purchase of the minority partner’s share. Thus, the majority partner looking to sell their stake harbors the risk that a potential buyer might walk away from the deal given the uncertainty over the size of the stake being sold, the associated capital required for the deal, and the post-close ownership structure. This can lead an exiting partner to seek an early commitment from the minority partner about whether it intends to exercise its tag-along right, although it is under no obligation to provide such assurance one way or another.

For those parties with a significant ownership stake and negotiating leverage in a venture, it would be remiss not to at least consider the inclusion of a drag-along right. The drag-along right enables the majority partner to force out the other parties to a venture alongside it. It also fundamentally differs from the previous exit rights discussed in this article in that it is a right belonging to the party initiating the exit rather than the remaining parties in the JV. In ventures with significant equity disparities or differences in negotiating power, it is in the interest of the more powerful party to have a drag-along right so it can exit at will and force the other party or parties to leave the venture alongside it. This may make the JV significantly more attractive to a buyer desiring 100% ownership of the company. Indeed, our data analysis shows that drag-along provisions appear most often as asymmetric rights belonging to the largest or state-owned parties with considerable negotiating power and leverage. While a drag-along right may be advantageous for a majority partner, it is a different story for minority parties, who may be unwilling to enter into a JV with a drag-along, which places them at the mercy of the majority partner. Minority partners should be particularly active in rejecting the inclusion of a drag-along right if they want a continued interest in the JV for strategic reasons such as because the JV is critical to their supply chain.

While ROFRs, ROFOs, tag-along rights, and drag-along rights are common at-will exit paths, dealmakers should be mindful that other exit mechanisms may be used. These range from a simple put right (i.e., the right to require your partners to buy your interests) or call right (i.e., the right to require your partners to sell their interests to you) to more complex buy-sell or put-call mechanisms. However, these rights are seen (in the aggregate) in 5% of agreements with at-will exit provisions, reflecting how a combination of ROFRs, ROFOs, tag-along rights, drag-along rights, and unilateral exit provisions are usually sufficient to meet the at-will exit needs of all parties.[2]Put and call provisions are often seen in exits triggered by the action or inaction of a single partner such as partner default or change of control. In particular, buy-sell provisions are particularly rare, both in relation to at-will exit provisions and more generally such as when a partner is at fault.

When crafting exit provisions, the parties should consider any adverse consequences that exiting at will might potentially cause, and ask whether any conditions are needed to ensure the JV’s success beyond the exit of a partner. Within these at-will exit clauses, we often find (a) a variety of limitations on the party initiating the at-will exit clause and (b) restrictions on the identity of the third-party buyer.

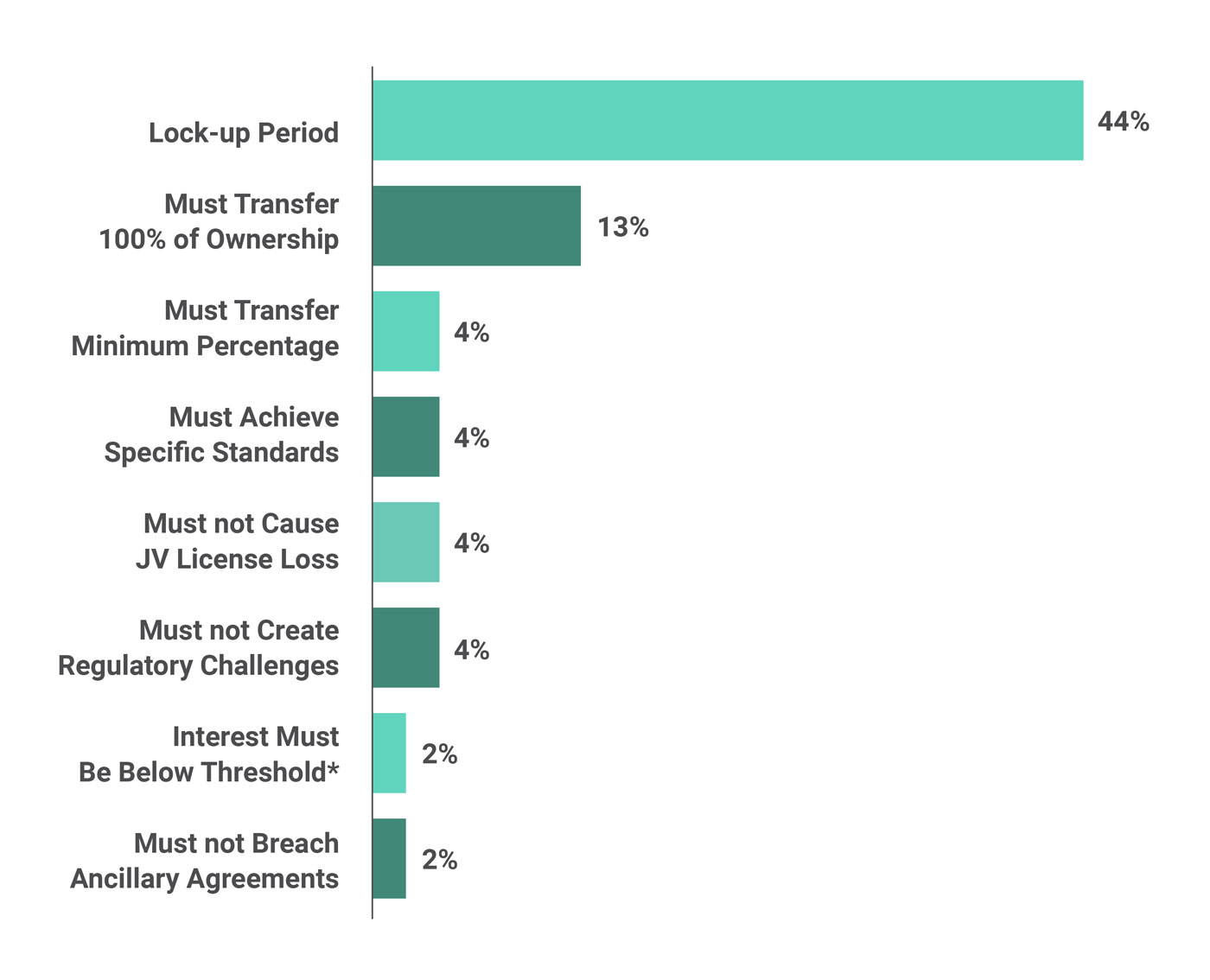

When drafting JV agreements, companies should be aware of an array of conditions that may be attached to at-will exit rights to prevent remaining parties from being left in the lurch without the exiting partner’s capabilities, technology, or other contributions to the venture (Exhibit 4). One of the most powerful tools dealmakers have in their toolbox is the lock-up period, a period from the venture’s start-up during which parties cannot exercise an at-will exit clause. The presence of a lock-up period signals the commitment of all parties to the JV and further provides certainty during the often crucial initial stages of the venture, enabling all parties to focus on getting the JV up and running rather than worrying about partners walking away. Our data reveal that some sort of condition or limitation is placed on the exiting party in 69% of all agreements where at-will exits are permitted, of which the lock-up period is by far the most prevalent. Lock-up periods are seen in 44% of such agreements, with a median length of five years, a considerable amount of time in which to get the venture off the ground.

* For example, a partner would only have the ability to exit at-will if it held 10% or less interest in the JV

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

Other conditions attached to at-will exit clauses focus on preventing partial transfers of equity and preserving the functional integrity of the venture. Many companies have learned from experience the greater the number of partners, the more complicated the functioning of the joint venture. To prevent situations where more and more partners are added to the JV, companies should consider including clauses prohibiting partial transfers of equity, mandating any party seeking to sell its interests must transfer 100% of its ownership and exit the venture unless otherwise agreed by the partners or JV board. Our analysis reveals this prohibition of partial transfers is the second most prevalent condition after the lock-up period, present in 13% of agreements in which exiting at will is permitted. Other restrictions only allow a partner to exit the JV at will if the JV has hit or failed to hit certain milestones. For instance, a two-party industrial JV allowed either partner to exit at will with the non-initiating partner given a ROFR only after a particular number of turnkey projects had been completed and a specified rate of return achieved. Other agreements stipulate that the initiating party’s at-will exit cannot cause the JV to lose particular licenses or create specific regulatory challenges. These clauses are important protections for any party remaining in the JV, but especially for those partners with a critical dependency on the products of the JV that lack the technical know-how to obtain these independently.

When crafting JV agreements, the parties may wish to consider placing restrictions on the identity of the third-party buyer as a method to protect non-exiting parties and the integrity of the JV moving forward. These restrictions typically relate to the competitive position, capabilities, or government affiliation of a potential new owner. Our analysis reveals that stipulations or conditions are placed on the buyer’s identity in a third of cases (Exhibit 5) with the most prevalent related to competition. When it comes to competition, a situation that JV partners want to avoid is a key competitor being brought into a deal and gaining access to specialized technology or intellectual property (IP), which might boost its know-how and offerings at the expense of the remaining JV partners. To counter this possibility, 31% of agreements with restrictions on the buyer’s identity specify the third-party buyer must not be a competitor of the remaining parties in the joint venture, while 19% of agreements go one step further in banning the sale of venture equity to specific named companies. For example, in the Verizon Wireless JV between Verizon (55%) and Vodafone (45%), both companies were prevented from selling to any company upon a specified “Restricted Entities” list agreed to in advance by both Verizon and Vodafone.

Similarly, the agreements might be structured to require a third party that is purchasing interests in the JV to possess certain capabilities or other characteristics related to size or financial strength. This can be quite important if the JV depends on one partner for certain technologies, skills, assets, or financing. We found that 25% of agreements placing restrictions on the buyer established specific minimum capabilities of any third-party buyer. For instance, in a 33:33:33 industrial JV that operated a multibillion-dollar, world-scale production asset, each partner’s ability to freely transfer its interests required any third-party buyer to have at least a BBB credit rating, have defined annual sales or consumption of at least $1 billion in the relevant segment, and have “acknowledged international prestige.”

The third category of restrictions are those concerning government affiliation or geopolitical sensitivities. For example, the agreement may stipulate that a buyer must be government owned or affiliated or, by contrast, that government-affiliated parties are prohibited from obtaining a stake in the venture. Our analysis showed that such restrictions account for a quarter of restrictions on the buyer’s identity – often in the aerospace and defense or telecoms sectors. This includes a small minority of venture agreements that blacklist ownership by companies domiciled in or doing business with particular countries.

Such restrictions may be intended to safeguard the remaining partners; they may also bolster one partner’s exit position. For instance, in the 33:33:33 industrial JV, the exit restrictions radically reduced the universe of potential buyers and precluded private equity firms and many Chinese companies from being on the acceptable buyers list. The net result was when the industry shifted and two partners wanted to exit, the third partner was able to buy out its partners for pennies on the dollar.

While the right to exit a JV at the partner’s time of choice – even without a triggering event – is often sought, such rights rarely appear without limitations and qualification and must be tailored to the parties’ needs and desires. The type of provision desired will almost always depend on whether a party views itself as more likely to be the partner initiating the exit or not as well as on the business of the JV, the ownership stake of the partners, and other JV characteristics. Potential JV partners should assess merits and drawbacks of various exit mechanisms and other limitations on transfer before even entering negotiations with the counterparty(ies). Moreover, companies must be aware such rights may be tricky to exercise in practice. For example, the inclusion of both a ROFR and tag-along rights would likely attract only the bravest of buyers, given the uncertainty over the size of the stake being offered (which would be larger if the partner exercises its tag-along right) and whether the deal will go through in the first place (which the deal would not if the partner exercises its ROFR). Stacking restrictions on the identity of the third-party buyer can narrow the pool of potential buyers so there are no feasible potential buyers. With proper consideration and thoughtful negotiation, these unilateral exit at will provisions can be a very effective means for a JV partner to exit a venture that is no longer providing adequate upside to justify retaining its stake.

Edgar Elliott is a Senior Associate, Tracy Branding Pyle is a Managing Director, and James Bamford is a Senior Managing Director within the Joint Venture & Partnership Practice at Ankura Consulting. The authors would like to thank Lois Fernandes D’Costa and Joshua Kwicinski for their contributions to this article.

We understand that succeeding in joint ventures and partnerships requires a blend of hard facts and analysis, with an ability to align partners around a common vision and practical solutions that reflect their different interests and constraints. Our team is composed of strategy consultants, transaction attorneys, and investment bankers with significant experience on joint ventures and partnerships – reflecting the unique skillset required to design and evolve these ventures. We also bring an unrivaled database of deal terms and governance practices in joint ventures and partnerships, as well as proprietary standards, which allow us to benchmark transaction structures and existing ventures, and thus better identify and build alignment around gaps and potential solutions. Contact us to learn more about how we can help you.