Managing Misalignment in Joint Ventures

JV agreements can be tailored to more effectively prevent, de-escalate, and resolve disputes.

A High-Level Overview

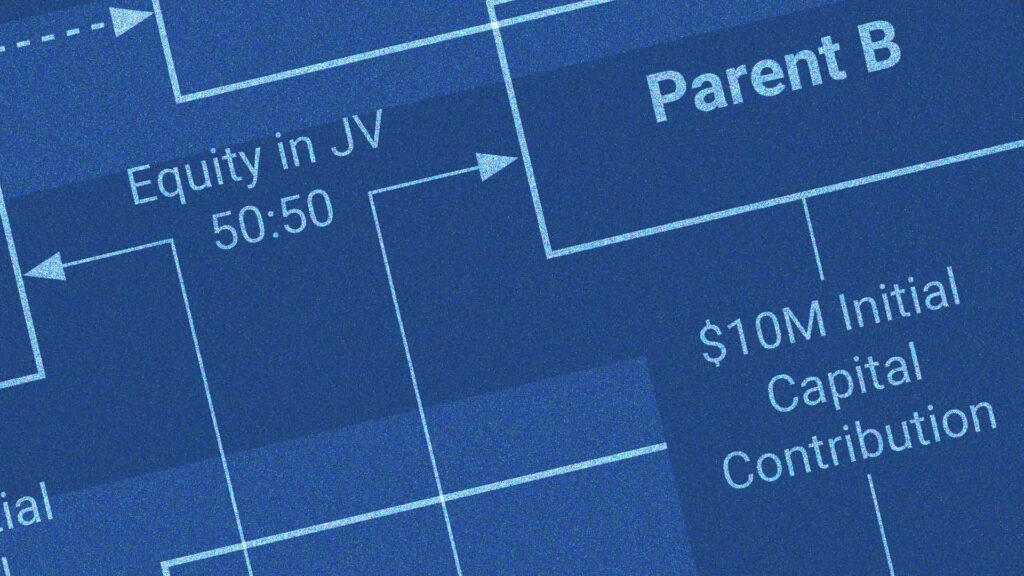

When potential partners are designing a joint venture, a key question is: What will each “bring” to the party – cash; tangible assets such as facilities, equipment, land, or inventory; or intangible assets such as technology, know-how, data, patents, brands, processes, customer lists, and market relationships?

Answering that question triggers a second one: How will the partner make those assets available to the JV? Will a given item be “contributed” to the JV in exchange for equity in the JV; loaned, licensed, or leased to the venture while retaining ownership; or simply sold to the JV in return for cash or other non-cash considerations?

Let’s look closer at each of these options.

If a partner contributes tangible or intangible assets to the JV, there are several implications. First, ownership of the asset passes to the JV post-close, and the parent no longer directly owns or controls it. Second, the parent making the contribution may receive equity in the JV for the value of this contribution. For example, in Exhibit 1, Parent A formally receives 25% of its equity in the JV in exchange for the technology it contributed and 25% from its cash contribution. This approach, directly tying asset value to JV equity, is most common when the asset is easily valued and the partners can agree on how much it should offset the cash contributions otherwise required to obtain a desired ownership interest. However, this is less clear-cut if the asset contributed is hard to value, as with intangible assets like intellectual property (IP). In such cases, partners may deem the contribution to have a specific value or agree to put it into the JV at no cost, deeming it equal to and offsetting to intangible contributions provided by other partners.

The third implication of a contribution is that it avoids the need to negotiate an ongoing commercial agreement with the contributing parent to use the asset. For example, no license agreement would be required from Parent A to the JV to use technology if Parent A contributed the technology to the JV. However, an ongoing commercial agreement may be required for the contributing parent to use the asset going forward. For example, if a parent contributes a patent for a particular process to the JV but still wishes to use that process in an existing plant, the parent might enter into a license agreement with the JV to give it such a right. These agreements could be for ongoing payments from the parent to the JV or at no cost, depending on the agreed-upon arrangement.

On the other extreme, the parent may retain ownership of the asset to be used by the JV and provide it to the JV under the terms of a commercial agreement (Exhibit 2). For example, the parent could lease land to the JV, license IP to the JV, or rent equipment to the JV. As above, there are several implications of this approach.

First, ownership of the assets in question stays with the partner, who then enters into a commercial agreement with the JV to provide it the right to use the asset.

Second, the partner may need to provide additional cash to the JV to receive its desired equity interest, since a partner does not receive equity in return for a commercial agreement. On the other hand, the partner may be comfortable holding less joint ownership while receiving unilateral economic benefits from its commercial arrangement with the JV.

Third, there will be an ongoing commercial relationship between the JV and partner that grants the JV certain rights to use the asset, which begs the question – how does the JV “pay” for those rights? The answer to this question varies significantly. The appropriate price for a JV-parent transaction should depend on the individual characteristics of the venture as well as the nature of the product, service, technology, or asset provided. However, pricing may vary and can be tricky to agree on.

In some instances, a partner sells assets to the JV, which it will then own post-close. Instead of receiving equity (as would be the case if the transfer was a pure contribution), the partner receives cash or another non-equity consideration (Exhibit 3). In such a case, the transfer is a pure arm’s-length sale to the JV. This can make sense if the parent companies want a specific ownership split at closing but the transfer of the asset will not occur until later. Instead, a partner can transfer the cash value of the asset into the JV at close and then receive that cash back in return for contributing the asset when able, without the transaction affecting venture ownership.

Partners can – and often do – choose a hybrid of these models. In such cases, the relationship has two or more characteristics of a contribution, a commercial agreement, or a sale.

One common hybrid approach is a parent licensing IP to the JV at the time of formation and receiving equity in the venture in return for agreeing to a royalty-free license. The license itself is an ongoing commercial agreement, but the economic benefits of the license are received solely through an equity share of the JV’s ongoing profits from using the technology – which makes the contribution of a royalty-free license something that can be valued as a source of equity in the JV.

Another common hybrid approach is a parent agreeing to provide a package of services, know-how, people, etc. at cost and to receive value for the contribution that is reflected in the equity. In such a case, there is a commercial relationship between the parent and the JV – either a service agreement, secondment agreement, or other agreement – but the willingness to contract without taking profit is rewarded with equity.

A final common hybrid approach is a sale and leaseback. In such a case, a parent sells land or buildings to the venture for cash and then leases all or a portion of such assets back from the venture under the terms of an ongoing commercial agreement that requires the parent to make ongoing payments to the venture. This arrangement may be helpful to the parent or venture for accounting reasons as the assets can sit on the venture’s books.

Hybrid approaches come in many flavors and styles and are specific to the nature and circumstance of the partnership. They can be used to bridge partner expectations when contributions or related-party transactions are challenging to price, or when neither a full contribution nor an arms-length commercial agreement seem appropriate.

How should JV partners tackle the questions of what partner assets the JV will use and how and when the JV will access such assets? We recommend that JV partners follow a four-step process (Exhibit 4).

First, we recommend partners make a list of all items the parties bring to the joint venture. This ensures all parties are aligned on what is coming to the JV from partners vs. third parties, and which partner provides each asset or capability.

Next, partners should inventory hurdles to the JV’s access to parent tangible and intangible assets. Does a lender need to consent to the transfer of the business asset the JV will use? Does the parent still need access to the asset? Do regulations or a permit prohibit a change in ownership? Knowing these constraints can help the partners appropriately structure how the JV will be able to use critical assets.

Third, the partners should review item-by-item to determine if items will be contributed to the JV, provided under the terms of a commercial agreement, sold to the JV, or accessed under a hybrid model (Exhibit 5). This approach will provide clarity for all parties and can link clearly to each partner’s business case for the venture.

Indeed, certain items parent companies bring to a JV tend to lend themselves to being formal contributions to the JV more than others. Factors that weigh in favor of a contribution include exclusive use of the item by the JV, distinct from partner operations, and easy to value. For instance, a piece of land that is located away from other partner facilities but will be used exclusively by the JV and has an easily discernable market value is a strong candidate to be contributed to the JV, with the parent receiving interests in the venture in exchange for the contribution. Complete business units or segments that go into a venture are similarly likely candidates to be contributions as the business is valued as a whole and becomes owned by the partnership.

By contrast, items that will be used by both the JV and a parent (especially if primarily by the parent), items that are co-mingled with other parent operations, and items that are hard to value may be better handled under the terms of a commercial agreement between the parent and the JV. For instance, if a JV will use a technical process used in most of a parent’s other operations, it likely is more palatable for the JV to license the process from the parent than for the parent to contribute the process to the JV and license it back. The latter approach would be quite risky for the parent, who would lose control of the ability to license a process core to its operations.

Hybrid approaches may come into play in special situations. For example, if a parent company has an emerging and unproven technology and the purpose of the JV is to see if the technology could work in a particular application, the parties may decide that the technology should be provided to the JV under the terms of a non-exclusive, royalty-free license. Such an approach would enable the JV to try to prove out the technology without incurring costs and would not prevent the parent from retaining ownership of the technology and trying to prove out the technology in different applications. This is a hybrid approach as it would be a commercial relationship, but the consideration for the license would come to the parent through profits in the JV, not through license payments.

Other special situations that may merit hybrid approaches involve cases where the value of a contribution does not align with the parents’ desired ownership split (e.g., the contribution is worth more than the contributing parent’s desired interest in the JV), when parties can’t agree on the value of a contribution, or when parties have differing views about the future of the JV (e.g., a partner can hedge its bets on the success of the JV by ensuring it receives at least some ongoing payments, even if discounted, from the JV for an asset it brings to the JV). Disparate views on valuation, JV risk, and JV likely performance can be addressed through arrangements related to what the parties bring to the JV, but alternatively, or additionally, can be addressed through ownership and control provisions.

Last, it is important to agree upon when assets will be conveyed to the JV. Often this is not on day one, but rather later in the JV lifespan. For example, in a manufacturing venture, a partner may provide operating services to the venture, but only after an initial construction phase during which the manufacturing plant is built and commissioned. The parties should align on when each parent-owned item to be used by the JV will be transferred or provided under the terms of an agreement.

Going through this four-step process can be complex and requires partners to reflect on what is fair in their particular circumstances. Ankura is here to offer advice and guide you through this process. We value tangible and intangible contributions, lead negotiation sessions to frame options and issues, provide benchmarking on how other JVs have approached contributions, and more. Contact us here.

We understand that succeeding in joint ventures and partnerships requires a blend of hard facts and analysis, with an ability to align partners around a common vision and practical solutions that reflect their different interests and constraints. Our team is composed of strategy consultants, transaction attorneys, and investment bankers with significant experience on joint ventures and partnerships – reflecting the unique skillset required to design and evolve these ventures. We also bring an unrivaled database of deal terms and governance practices in joint ventures and partnerships, as well as proprietary standards, which allow us to benchmark transaction structures and existing ventures, and thus better identify and build alignment around gaps and potential solutions. Contact us to learn more about how we can help you.

Comments