MARCH 2016 — CROSS-BORDER JVs continue to rattle across the newswires. In the last month, UK-based Vodafone and U.S.-based Liberty Global announced an agreement to consolidate their Dutch operations into a €3.5 billion 50:50 JV that will combine their respective positions in the country’s mobile and cable markets. Days before, KBR of the U.S. announced that its joint venture with Elbit Systems of Israel was awarded a major contract with the UK Ministry of Defence to support flight training. Days before that, Qualcomm of the U.S. announced a $250 million JV with a Chinese provincial government to design, develop, and sell advanced server-chip technology in China.

When companies enter into cross-border JVs they confront – sometimes subtly, sometimes not – national differences in Board governance. Among academics and corporate governance experts, national differences in Board size and structure, Director pay levels, and other features of corporate governance have long been a matter of curiosity.

But joint ventures are a place where those differences confront each other directly. And that can carry profound implications on how the JV partners design the Board and establish a coherent Board culture.

NATIONAL DIFFERENCES

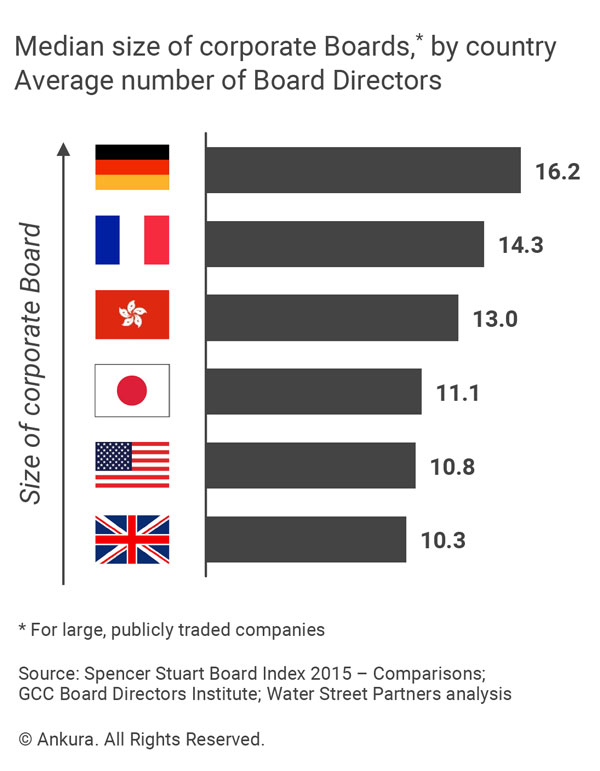

Corporate Boards around the world show some interesting structural differences. German corporate Boards are currently the largest in the world (Exhibit 1) and, along with Swiss, Danish, and Dutch Boards, are characterized by a two-tiered supervisory/management Board structure. Until recently, Japanese corporate Boards were historically very large (e.g., 30+ Directors) and dominated by management insiders. This changed dramatically in the late 1990s, as Japanese companies came under pressure to improve performance and adopt global corporate governance practices. U.S. and UK corporate Boards remain among the smallest in the world, and – unlike German Boards – are comprised of a large majority of independent, non-executive Directors. U.S. and UK Boards differ in whether they separate the roles of Chairman of the Board and CEO – the UK favors such separation (99% of large public company Boards), whereas the U.S. does not (48%).

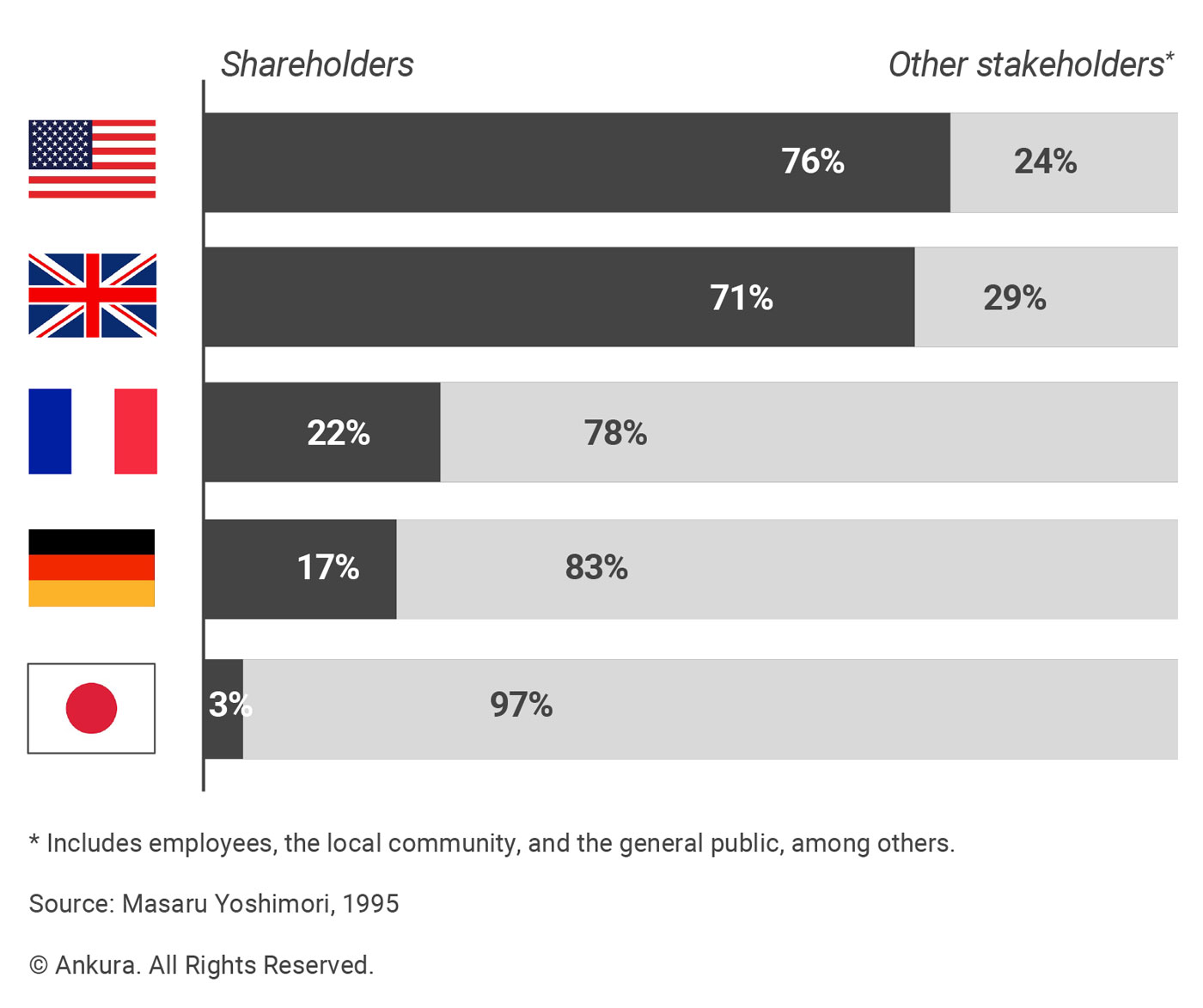

More interestingly, countries also hold different underlying beliefs about the fundamental purpose of a Board. For example, in the U.S., public opinion holds that Boards exist almost entirely to promote and protect the interests of the shareholders (Exhibit 2). This is absolutely not the case in Germany, Japan, or China – where society expects a Board, to varying degrees, to represent the shareholders, employees, the community, and the public at large (alongside shareholder interests).

Exhibit 2: Whose Firm Is It?

There are many reasons for these national differences. Some relate to the structure of public company shareholding – notably, ownership concentration, the nature of bank involvement, and state ownership. For example, in countries marked by concentrated ownership (such as Germany, Sweden, and Japan) Board composition tends to mirror the company’s most important long-term shareholder relationships. In Germany, large commercial banks, through proxy voting mechanisms, often control over a quarter of the votes at major companies – and may have further control as direct shareholders or creditors. In the U.S., where companies tend to have a highly dispersed shareholding, the Board does not reflect major shareholders, but is rather appointed to represent the individual main-street investor.

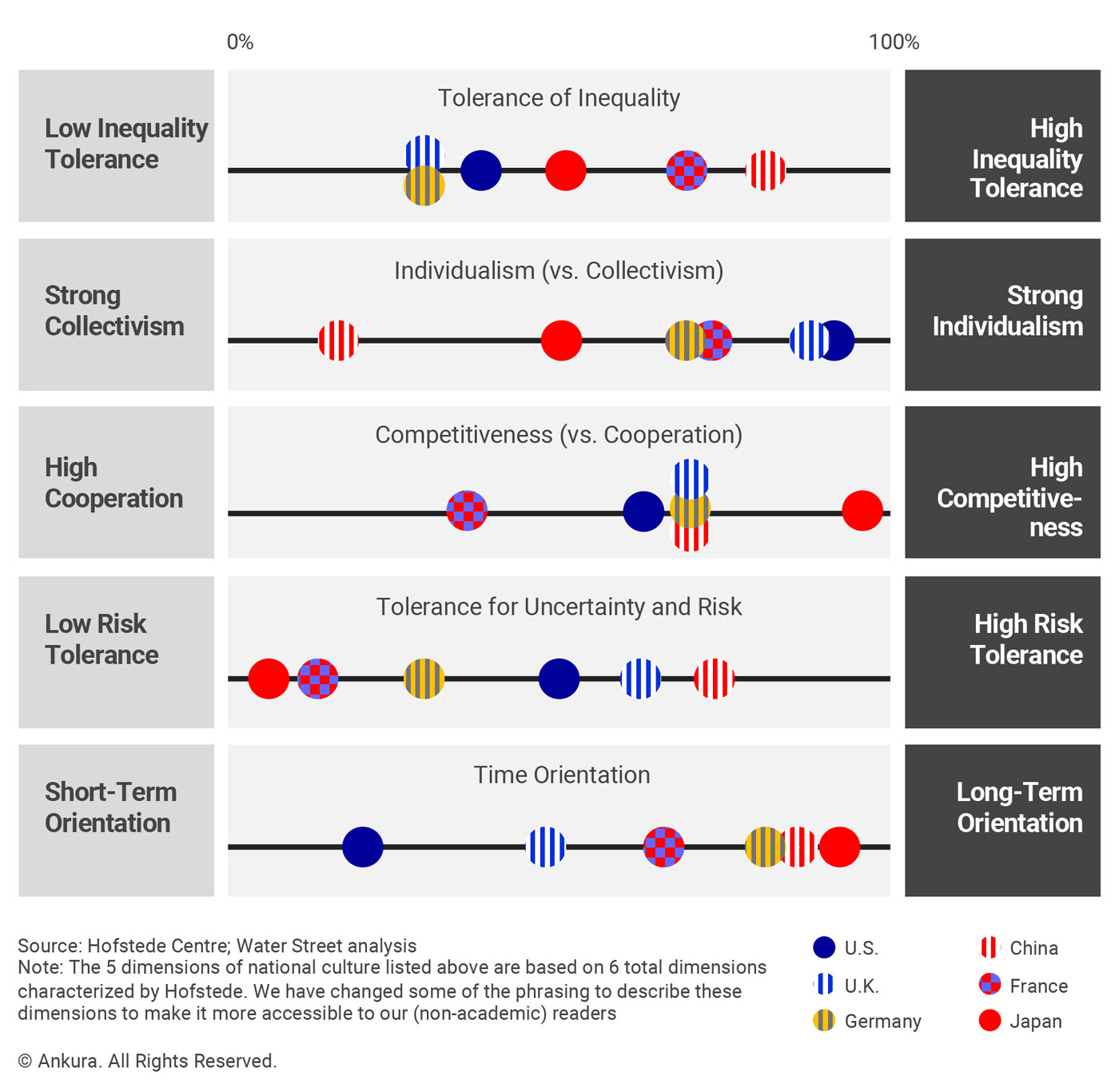

Corporate Board design and decision making also reflect national culture. One way to view national culture is through the different lenses developed by pioneering social psychologist Geert Hofstede: Tolerance for inequality, individualism, competitiveness, tolerance for uncertainty/risk, and time orientation. Different national cultures land on very different spots on these dimensions (Exhibit 3).[1]Geerf Hofstede, “National Culture,” The Hofstede Centre. April, 2016. http://geert-hofstede.com/national-culture.html For example, the U.S. has a national culture that values individualism, has a short-term orientation, and has a moderate risk tolerance. Given this culture, it is not surprising that U.S. corporate Boards are smaller and delegate more power to the CEO than do continental European or Asian Boards. Notably, research has shown that smaller Boards are more comfortable with risk than are larger Boards, where hesitations expressed by one Director can lead to deliberation and caution.[2]See Corporate Governance: The international journal of business in society. Volume 16. Issue 1 (2016). Smaller Boards also have a harder time challenging the CEO – especially a CEO who is also Board Chair – than do larger Boards, where alternative centers of power and political coalitions outside the orbit of the CEO have space to form.

Exhibit 3: Big Impact of Board Decision Making

IMPLICATIONS FOR JV BOARDS

These national differences among corporate Boards make for fine chatter and charts among corporate governance experts, eager to show their global orientation. But in cross-border joint ventures, these national differences actually matter. After all, in cross-border JVs, Directors on the same Board take their seats holding divergent national traditions of governance. These views are often reinforced through mandatory Director training programs conducted by the appointing-shareholder’s in-house legal department – training that is deeply steeped in the corporate governance and regulatory traditions of their home country. Because of divergent national traditions on governance, JV Directors may have different points of view for various items, including:

- Extent to which the Board should delegate decision-making authority to JV management

- Extent of Directors’ involvement in the operational workings of the business, including requesting information, and meeting directly with management, employees, customers, etc. outside of the Board setting

- Expectations of a JV Director in terms of representing and promoting their own shareholder’s interests, versus the Director’s moral and fiduciary duty to the JV and its collective interests

- Legal implications of conflicts of interest, and requirements and methods for managing such conflicts

- Other laws that apply to JV Directors and their liability for misconduct

- Participation, attendance, and remuneration of Board Directors (and committee members)

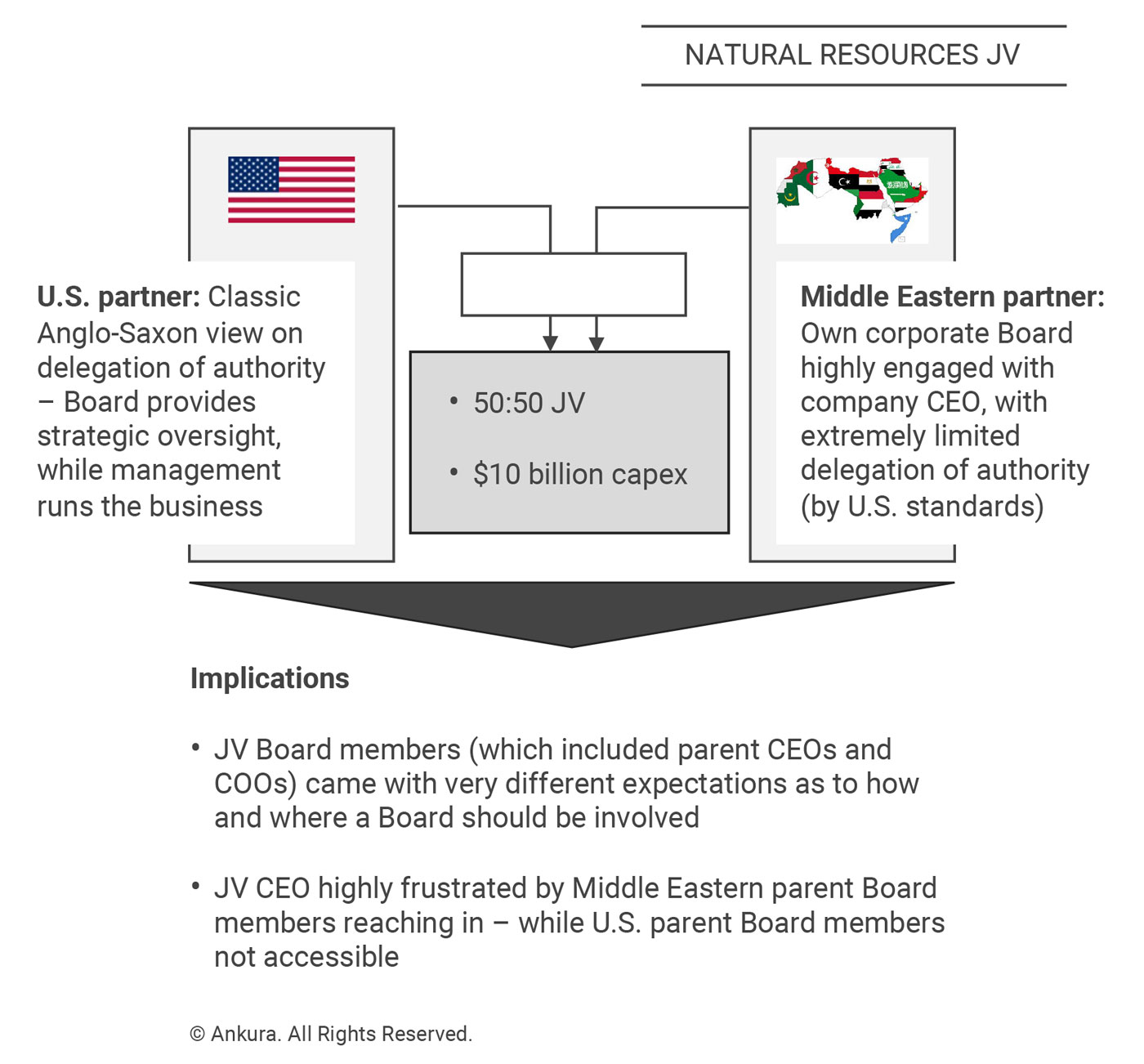

Client Example

Consider a large cross-border joint venture in the Middle East that was suffering from fundamental misalignment in governance philosophy (Exhibit 4). The JV was owned by global company based in the U.S., and a local Middle Eastern firm. The 50:50 JV was formed to create a national champion in a critical new industry. As a giant first step in realizing this ambition, the partners committed $10 billion to develop, build, and operate a worldclass production asset in the country. The Shareholders’ Agreement called for an eight-person Board, with representation split evenly between the partners. The U.S. company appointed its BU CEO, VP Finance, VP Technical, and a senior operating executive to the Board. In contrast, the Middle East partner appointed its CEO and three of its corporate Board members to the joint venture Board.

Exhibit 4: Cross-Border JV – Cultural Differences

This was the first obvious signal that the partners were approaching board governance differently.

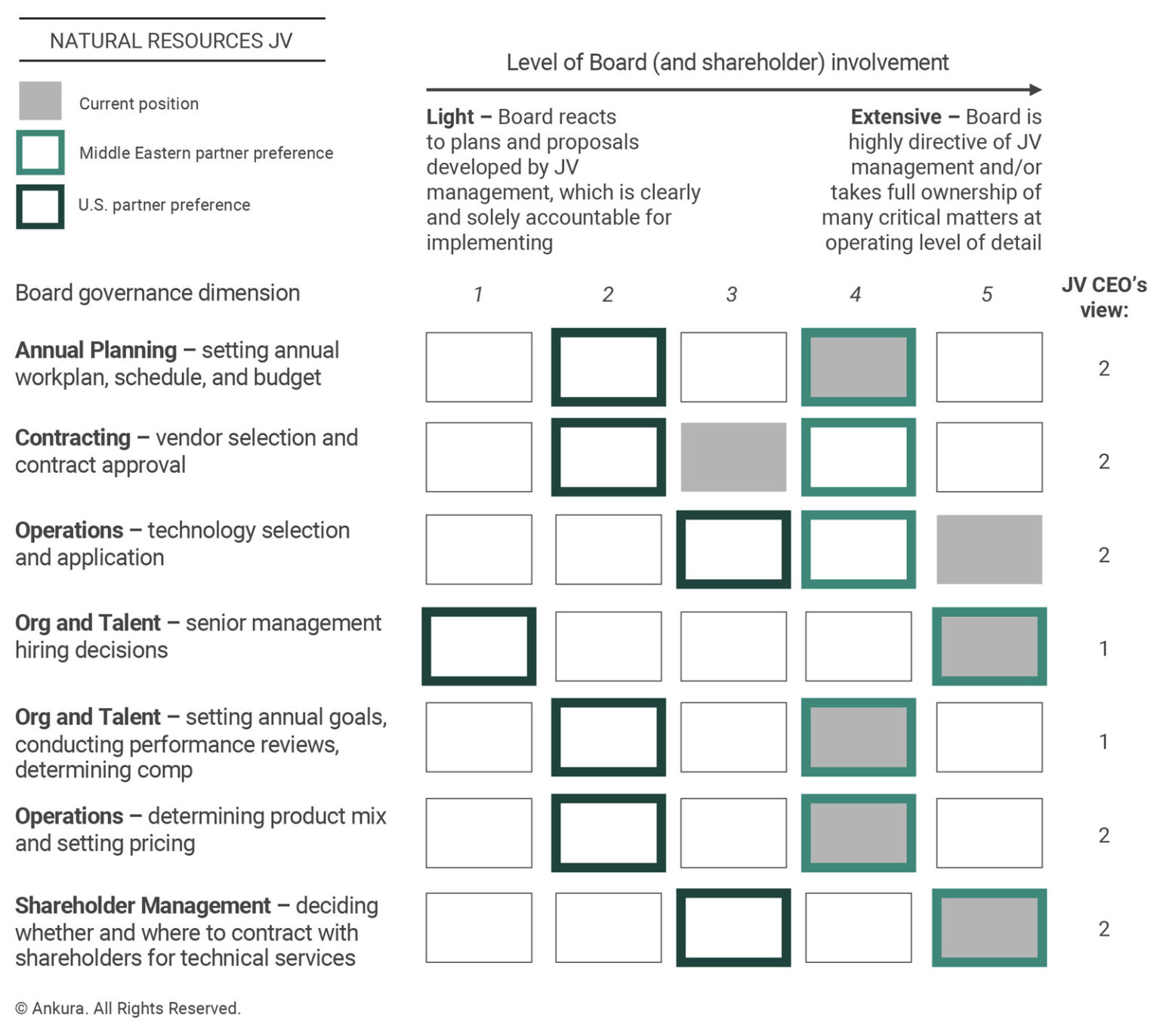

Across the first 18 months of Board meetings, frustrations were mounting, due in part to the different national traditional of corporate governance. The U.S. executives believed in clear accountability and strong delegations of authority to the CEO. They believed the role of the Board was to assemble quarterly, where the Directors would react and challenge proposals and plans developed by JV management. The Middle East partner had a different mental model. Its own tradition of corporate governance was one of highly active Board involvement. Its Directors believed that the role of the Board was to aggressively challenge – and in many cases direct – the CEO. They also believed that individual Directors would regularly meet with the CEO and JV management outside of Board meetings, to maintain a feel for and close relationship with the business. These differing philosophies collided on the JV Board. For instance, when we asked the JV Directors to characterize their personal views of the desired level of Board involvement across different dimensions of Board governance, their responses revealed fundamentally different concepts about the joint venture Board (Exhibit 5).

The JV CEO felt this misalignment most acutely. As a secondee from the U.S. partner, he shared his parent company’s governance tradition. Indeed, in his negotiations to accept the job, he was led to believe that he would be empowered to be the CEO of a new business – and expected to have the “full range of motion” of a CEO in a U.S. context. But time and again, the Middle Eastern shareholder, including Board members and operating executives not on the Board, reached deep into the business, jumping over what the CEO believed were boundaries between governance and management. They requested volumes of information. They asked for third-level operating details, and legal terms of all vendor contracts – including those that were immaterial to the business. And they regularly met privately with venture management and staff, including secondees, at times guiding and prioritizing their day-to-day work. Deeply frustrated, the JV CEO commented:

I’m about to bite someone. I thought I negotiated for a fairly long leash – but my feet cannot even touch the ground! What’s more, the Board keeps erecting invisible fences preventing me from growing this business in areas where it needs to go.

Through a series of diagnostics and workshops, we worked with the Board to overcome their divergent national traditions of corporate governance, and to define a coherent governance model that blended their separate traditions, and that was appropriate for the venture they were trying to build.

Broader Implications

Such issues raise important questions for companies and executives involved in cross-border JVs:

Director Accountabilities and Expectations

What exactly do we expect of our executives appointed to a JV Board?

- What are the local governing laws and standards that apply to this JV? To what extent might these conflict with our incoming expectations for Directors, given our own national culture and tradition?

- What practical accountabilities and decision-making rights will Directors have in this JV? What legal expectations will they need to manage?

- How should JV Directors be expected to interface with JV management, shareholders, external stakeholders, and each other?

Board Model and Culture

What Board model are we trying to build with our partner, and how will we create a cohesive culture on the JV Board that recognizes and blends any incoming differences?

- What is the right Board posture for this JV, given the risks, performance, and overall strategic intent? For instance, do we want a corporate-style Board (that is more deferential to management) or a quasi-operating Board (that is highly directive of management)?

- How do we translate this desire into a Board culture, and should we memorialize these views in a set of Guiding Principles or other governance framework document?

- During the launch planning phase (or within the first 100 days post-close) should we expand the cultural “workouts” to include sessions on Board culture (not just the JV’s organizational design and culture)?

- What role do the parent companies’ Lead Directors (if present) play in ensuring a cohesive and integrated Board culture?

- How will we monitor the Board’s model and culture?

Director Training

At a corporate level, how will we train our executives asked to serve on JV Boards?

- To the extent that our company is entering into JVs in international markets or with foreign partners, how should our JV Director training program discuss different national cultures of governance, and offer ideas for how to address these differences on a JV Board?

- Are the benefits of sending JV Directors to external Director training programs within our country (e.g., offered by the National Association of Corporate Directors in the U.S., or the Board Directors Institute in the Gulf region of the Middle East) outweighed by the risks that such training does not reflect national differences or prepare a Director for the unique environment of a joint venture?

Advanced JV Board Governance Demands

In certain JV situations, the cultural differences on governance take on an even higher degree of difficulty. Examples include:

JV Boards with Government Involvement

Some cross-border JVs, especially in places like China, Africa, the Middle East, and other major natural resource-holding emerging markets, government officials may be Board members through a state-owned partner. In China, the government will often appoint a “party observer” to the Board.

JVs with Numerous Partners from Different Countries

Roughly 40% of JVs have three or more owners – and some JVs have owner groups far larger than that. Star Alliance and SkyTeam, two global airline alliances, have owners from more than 20 countries, each of which are represented on the venture’s Board. The financial services industry has numerous shared industry utilities, such as SWIFT and Euroclear, which have similar or greater levels of national diversity.

JVs with Management Teams from a Different Country than the Owners

In some cross-border JVs, the venture itself is located in, and managed by executives from, a country different from either owner. One prominent example is PGT Healthcare, a Switzerland-based multibillion dollar global over-the-counter healthcare products joint venture between Procter & Gamble of the U.S. and Teva Pharmaceuticals of Israel. Another is Tinguiririca Energía, a 50:50 hydropower JV between Norwegian and Australian owners, which is located in Chile.

In these culturally “higher-order” JVs, navigating national cultural differences on governance is even more challenging and necessary.

Cross-border JVs are not going away. Isn’t it time to increase the sophistication for how the Boards of these entities are designed? We think so.

Comments