JUNE 2011 — That question might sound ridiculous. Committees are not known to strike fear into great leaders. Nor are they known for their speed, decisiveness, or command of real power and resources.

And that is precisely the problem in joint ventures.

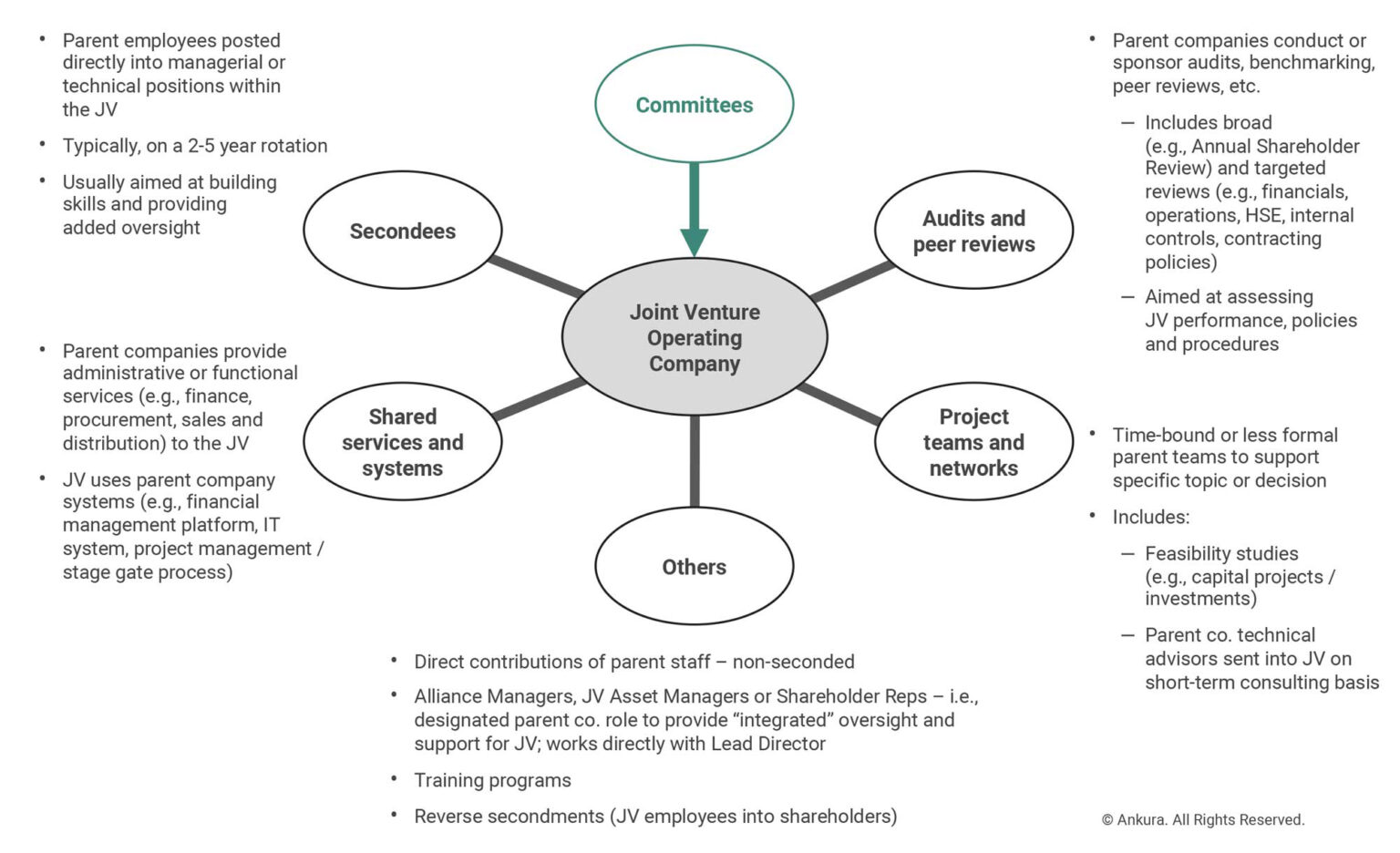

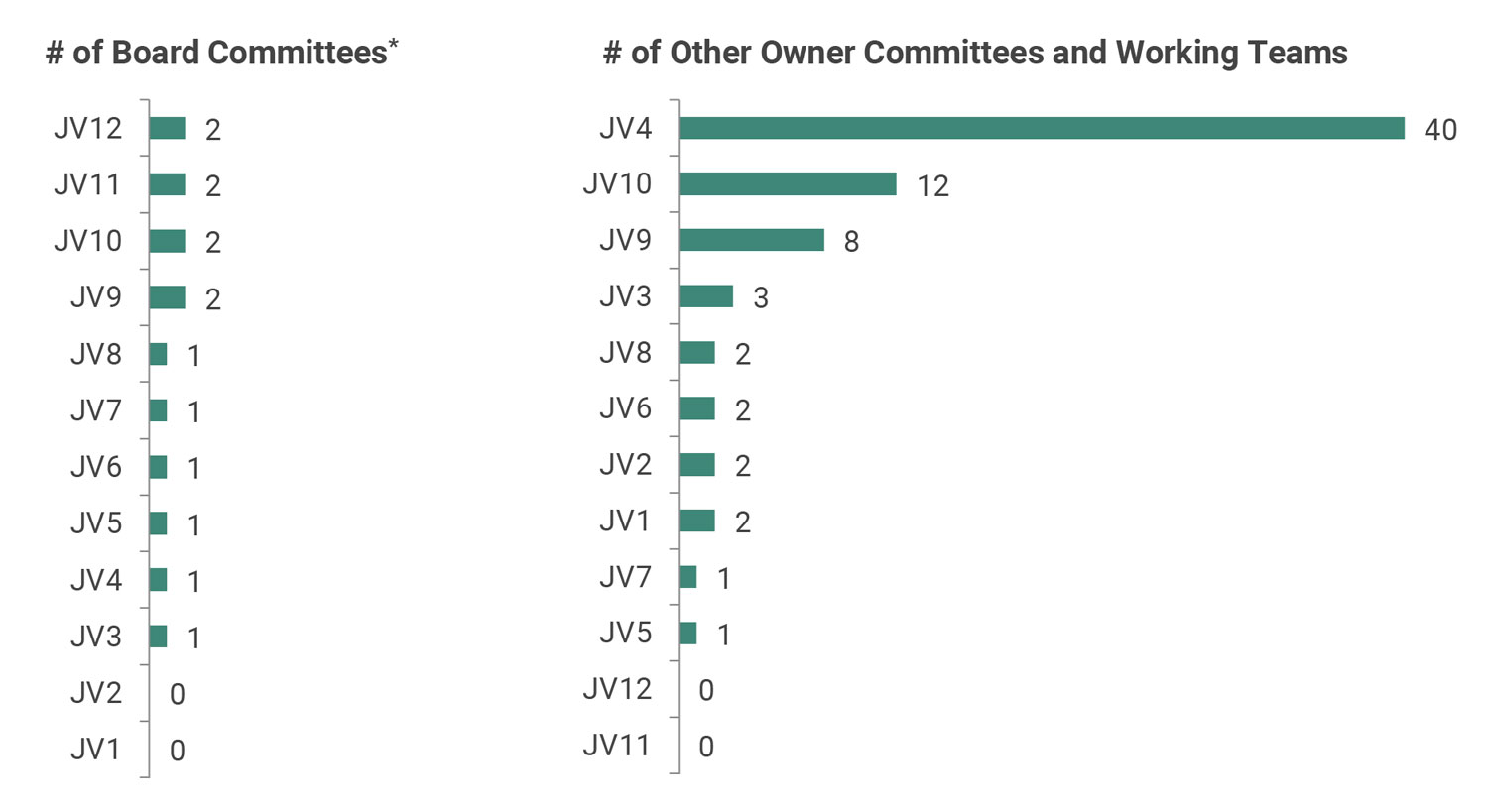

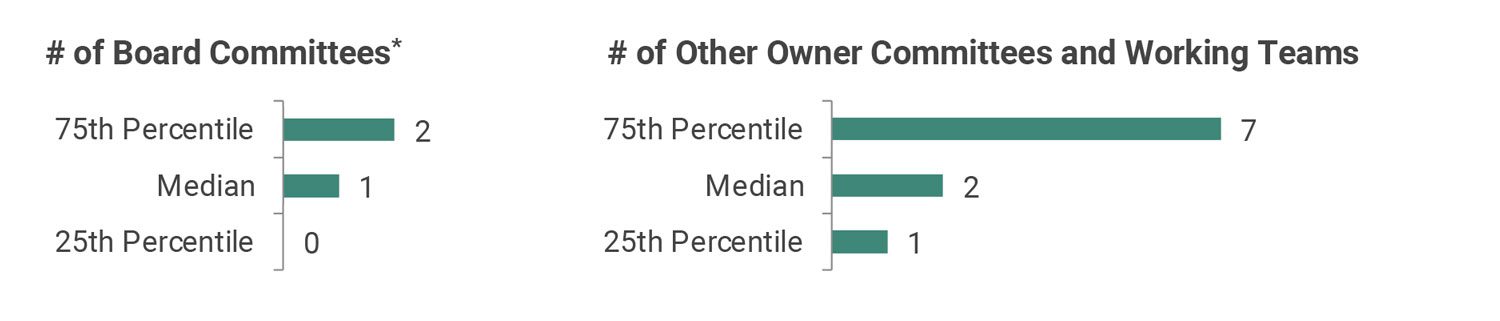

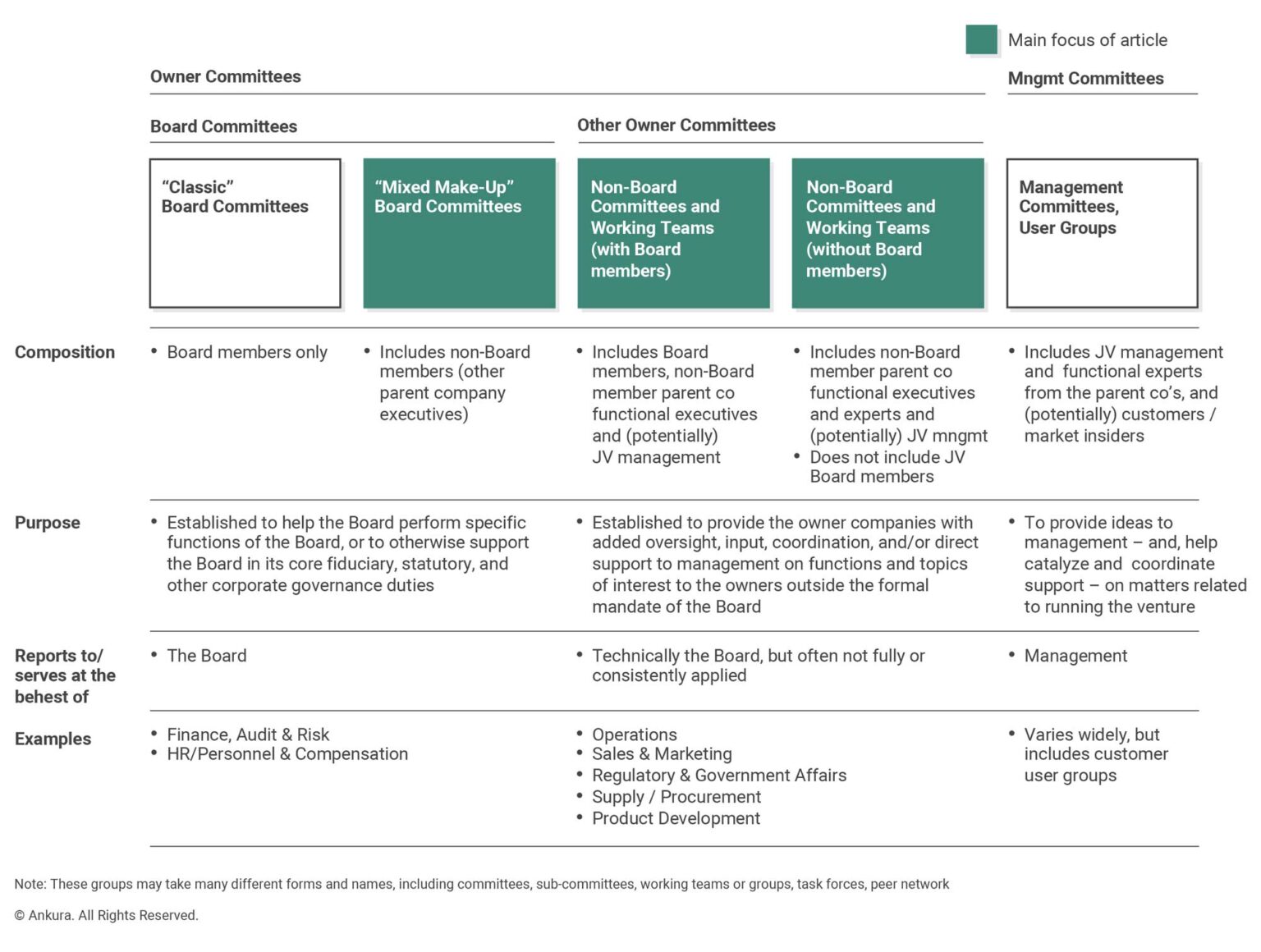

Sketch out the governance and organizational structure of a joint venture, and you’ll often find at least a few – and sometimes far more – Board and other owner committees, sub-committees, and working teams operating in the never-never-world between the Board, the Shareholders, and Joint Venture Management (Exhibit 1). Most are not classic Board committees but, rather, committees charged with performing narrow roles beyond the mandated functions of the Board or mainly comprised of functional experts from the parent companies who do not sit on the Board (Exhibit 2). They are created to provide “input” to venture management, deliver an added level of “assurance and oversight” to different aspects of venture operation and new capital investments, and “advise” the Board on specific matters such as budgeting and planning, product development, vendor selection, manufacturing and operations, marketing and sales, and government affairs.

Sounds useful.

But committees can be a formidable threat to joint ventures. The purpose of this memo is to outline where JV committees go bad, and to show how JV Boards and CEOs must actively manage such groups to ensure they contribute to – rather than undermine – venture performance. To be clear, this memo is not aimed at classic Board committees;[1]Classic Board Committees include: (1) Finance, Audit & Risk, and (2) Human Resources/Compensation. We view these two committees as needed in most JVs, although they are each present in less than … Continue reading rather, its focus is on other types of committees that tend to be spawned over time within the broader stream of joint venture governance.

Exhibit 1: Committees, Committees Everywhere

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

THE PROMISE AND PERILS OF COMMITTEES

The Promise

Committees and working teams have a legitimate role to play in many JVs. They can help deliver expertise to a venture that lacks the scale to hold certain specialist skills in-house. They can alleviate some of the burden of governance – especially in domains where Board members lack the time or expertise to perform adequate oversight on their own. And they can provide a mechanism for operational staff within the shareholders to coordinate with each other,[2]For example, in an emerging market power JV, the shareholders created an Economics & Risk Committee to help align their organizations on key macroeconomic assumptions (e.g., local energy demand … Continue reading or to gain a preemptive “voice” into key venture decisions (e.g., product development, sales strategy) that could have a strategic impact on the shareholders’ businesses and assets held outside the JV.

As the director of a large mining JV in the project development phase explained to us:

We’re desperately keen to keep functional experts engaged and involved in the JV. Committees are our best way to do this. We see committees as a safeguard against “rogue management” – and, more importantly, as a way for technical experts to agree on basic assumptions about the market, the geology, the technical specifications for contractors, and the integrity of the larger technical plans to exploit the resource.… And to do this before all the political bargaining at the board begins.

Committees are certainly not the only way for shareholders and management to fulfill these objectives (Exhibit 3). Secondees, peer reviews, audits, technical and administrative shared service agreements, use of parent company processes and systems, short-term rotations by shareholder engineers and staff – all are alternative means of meeting many of the same goals.

Exhibit 3: Not by Committees Alone

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

But committees often have a role to play. Our database of several hundred JVs shows that three types of JVs tend to establish non-Board committees with the greatest frequency:

- Large, capital-intensive natural resource JVs: When natural resource companies like ExxonMobil, Total, or Rio Tinto invest billions of dollars in large jointly-owned assets, they tend to establish function-specific committees from the earliest stages of project development. Initially, committees drive many critical elements of project design and evaluation, including technical and commercial feasibility. Over time, as a project moves into construction and then operations, committees are retained (hopefully with some re-scoping of roles and authority levels), with their purpose switching more to oversight and decision support.

- Multi-owner JVs providing a core technology platform: Another class of committee-using JVs are entities like Star Alliance (airlines), Next Issue Media (online magazine platform and distribution), and SWIFT (global financial settlements) – that is, ventures with large numbers of owners usually aimed at creating a common technology platform and new products for their owners. Here, the JVs use committees principally as a means to secure product and market input from operating-level managers within the shareholder companies.

- Other JVs with significant sales or product-related interdependencies with the shareholders: Finally, there are those bilateral ventures that leverage their shareholders for significant assistance (and work) along the value chain – from product development, to manufacturing, to marketing and sales. JVs in this category include Merck-Schering (pharmaceuticals), work-sharing JVs in aerospace and defense (e.g., CFM), and Nissan-Renault (autos). When committees and working teams are used in such ventures, they tend to be mechanisms to coordinate specific functional workstreams occurring within the shareholders (and venture).

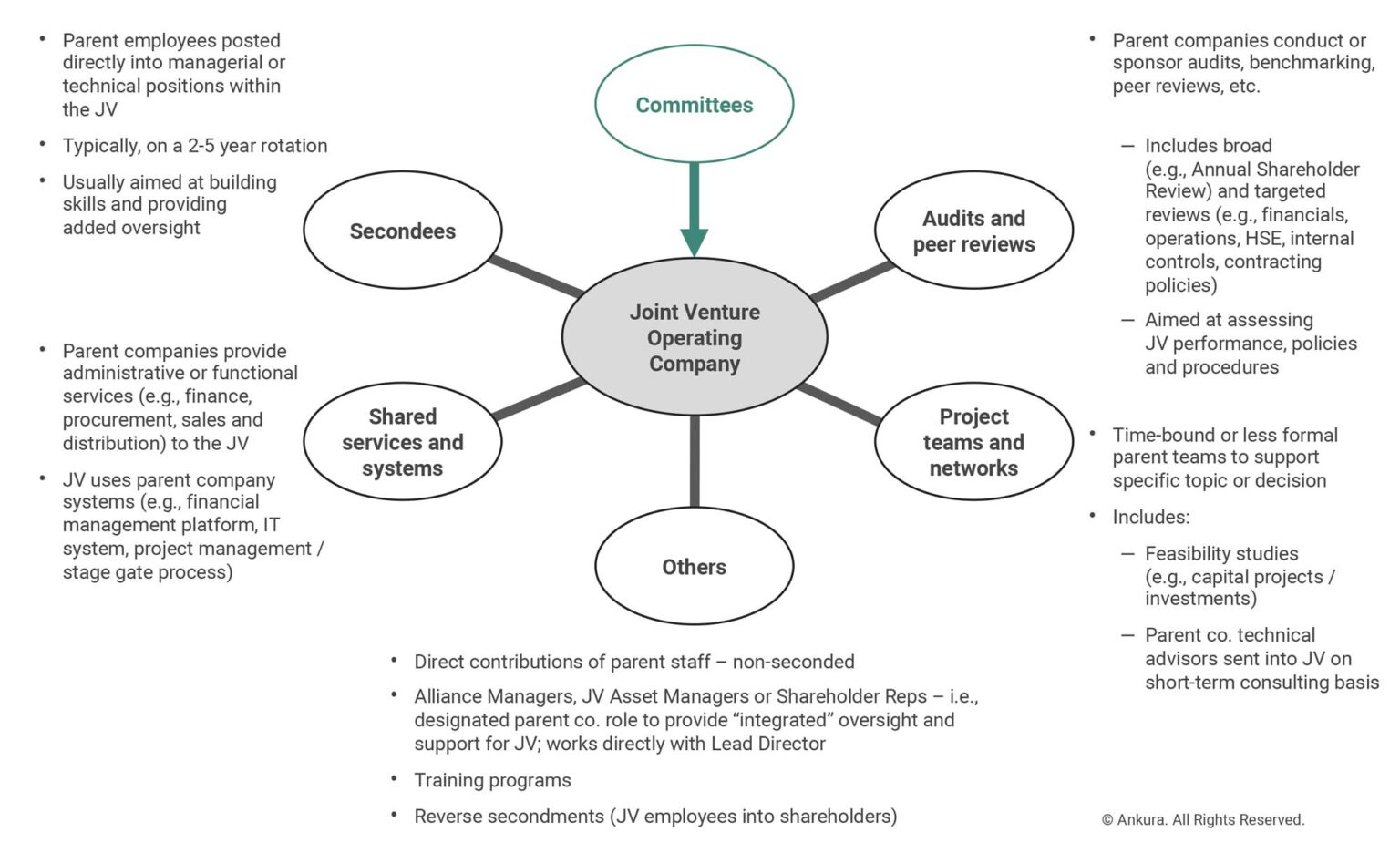

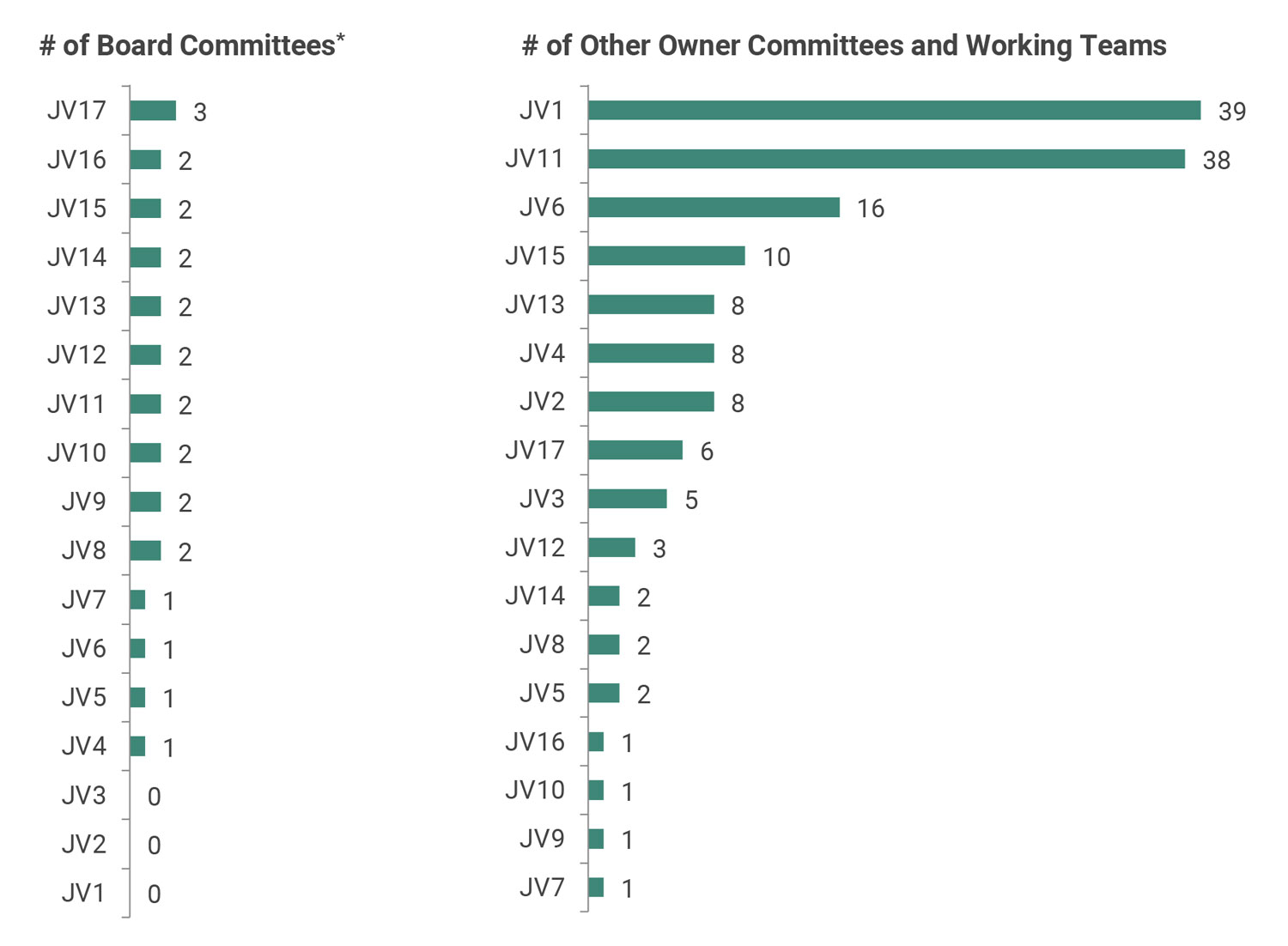

Most JVs have at least a few committees and working teams, which can appear in different forms and guises (Exhibit 4).

The Perils

Unfortunately, many JV committees don’t deliver on their promise – and may even introduce added costs and risks. As JV Board Chairs, Lead Directors, other Board members, and the JV CEO look at their non-Board committees, it is worth testing whether the venture is falling into any of the following five common pitfalls:

- Lack of clarity (and enforcement) on the role: What is the fundamental purpose of the committee and its members? Is the committee there to provide “help” to the venture, by providing ideas and access to data and resources inside the parent companies? Alternatively, is it to “oversee” management, and provide additional assurance that the Board simply does not have the time or expertise to do? Or, is it to “coordinate” activities – for instance, on sales and marketing or regulatory affairs – where the parent companies and venture staff are each engaged in work? Or, perhaps, is the committee there to do something else – e.g., to simply serve as a forum to share ideas or to perform analysis (e.g., sizing adjacent market opportunities, developing a common view on macro-economic risks and conditions)? A committee may have more than one fundamental role, of course. But all too often, that purpose is ill-defined or misunderstood.

Exhibit 4: Committee Use in Selected JVs

Natural resource industry JVs**

Other industry JVs**

Summary data** (N=56 JVs)

Note: this chart displays a selection of natural resource and other industry JVs from our database, chosen to highlight the high and low ends within each data set

* Classic Board committees include Finance, Audit & Risk, and HR / Compensation. In our database of hundreds of JVs, only 64% have Board-level Finance, Audit & Risk Committees, while 55% have HR / Compensation Committees

** Source: Ankura JV Database

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

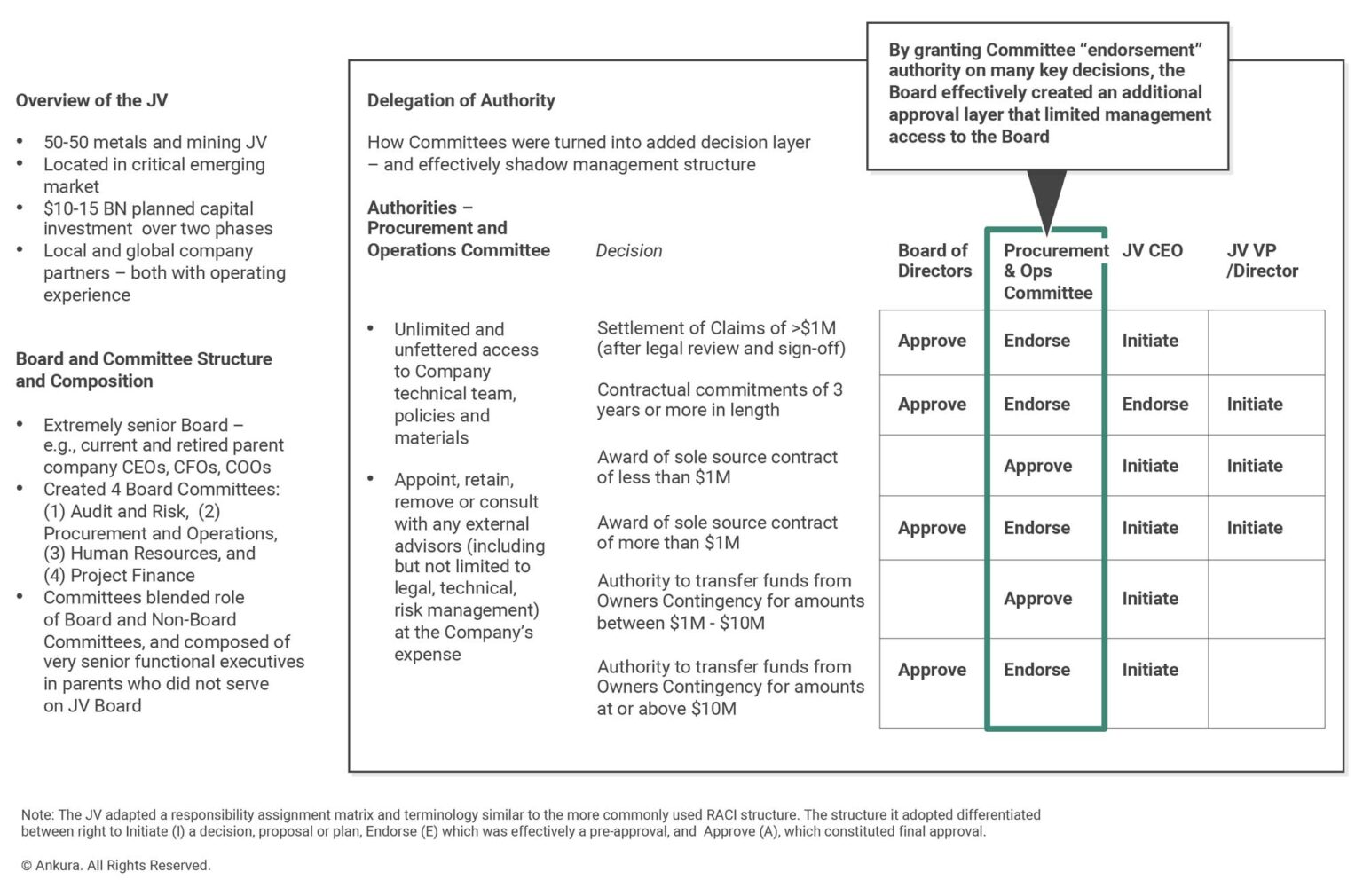

- Creation of a disconnected “quasi-approval” layer in the governance system: In most cases, non-Board committees and working teams are not vested with formal decision making power – and serve in an advisory capacity to the Board or management. The reality is often something quite different. In many cases, a JV Board will look to an endorsement from a committee before it reviews and approves a management recommendation (say, the choice of a contractor, annual product roadmap, or project financing plan). While the Board may not have intended to delegate power to the committee, it effectively has done so – or at least added another layer in the approval process. And when such committees comprise functional executives – rather than Board members – it means that the CEO is effectively reporting to separate groups on key functional matters (Exhibit 5).

- Failure to adequately assist the venture in accessing skills or resources – or catalyzing action – inside the shareholder companies: Committees and working teams need to be “active contributors to venture success.” That does not mean simply leaning back and critiquing management. Rather, it means committee members utilizing their understanding of, and relationships inside, their companies to help the JV get the resources and visibility it needs to succeed. For instance, this might mean helping the JV find a technical expert to help on a specific matter. Or it might mean sharing with JV management aspects of the company’s strategy or product roadmap, thereby allowing management to better link its own plans to those of the shareholder. Most committees ignore this role almost completely.

- Enabling of extended “proxy wars” between the shareholders: While non-Board committees can be an important forum for the functional experts to work through issues, they can also degrade into battlegrounds for the shareholders to fight extended “proxy wars.” For example, in a large LNG joint venture, the technical committee kept debating (and not deciding) on a plan to refurbish and debottleneck (i.e., increase the capacity) the asset. It turned out that while certain committee members from one owner were challenging technical aspects and line-item costs of the proposed capital project, the reality was that their company was interested in deferring the investment for 18-24 months. The reason: the company had its own capital project planned on a nearby asset, and did not want to compete with the JV for talent, regulator approval, and contractor attention. Rather than having a direct conversation at the Board – and deciding to defer the project for a year – the committee members’ tactics drove JV management into a frustrating and unnecessary stream of work trying to satisfy the stated issues of the committee.

- Imposition of significant time demands on venture management: Unchecked, committees and working teams can generate significant time demands on management via information and internal reporting requests, meeting preparation, site visits, and the like. When a JV has more than a few such committees, the overall burden might exceed 10-25% of the time of the JV CEO, CFO and other senior venture management.

Exhibit 5: Turning Committees into a “Shadow Management Team”

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

The Costs

Add all these problems up, and you’ve got some real costs: Delayed decisions, the penalty of which falls on JV management. Weakened accountabilities. Added time and resource demands on management. Missed opportunities to deliver available skills to the venture. And, well, just a perception of bureaucratic inefficiency.[3]A decade ago, The Economist commented on the emerging structure of the Star Alliance: “Star has no fewer than 24 committees to sort out such matters as network connectivity, purchasing and customer … Continue reading

The Culprits

When JVs suffer from committee problems, the path usually leads to a fairly predictable cocktail of root causes. Often times, committees have ill-defined, outdated, or poorly understood mandates. In other instances, committees lack accountability – including clear objectives established by and a reporting chain back to the Board and JV Management. And, often, committees are not comprised of the right people. (For instance, they may have highly-conflicted participants trying to balance their role in parts of the business that compete for internal resources.)

Make no mistake: the blame does not always belong on the committee or its conceivers. In some cases, the JV Management sidesteps or under-leverages a valuable committee. Consider a large upstream oil JV. The JV had an immediate need to invest $50-100M in an emergency pipeline repair system to ensure integrity of supply. Management issued an RFP to three contractors. Of the two contractors that responded, one was clearly superior, and well within the range of what the Operations Committee viewed as acceptable. Management quietly held a different view: it wanted to award the contract to the third contractor that had not responded to the RFP. Rather than seeking the Operations Committee’s input, management simply reissued the RFP. When it recommended the third contractor for the work, the Operating Committee and Board rejected the proposal based on their experience with the contractor in other projects. Management’s decision not to vet its plan with the Operations Committee to reissue the RFP to give the third contractor a chance to respond caused a six-month delay in the project – and exposed the shareholders to considerable and unnecessary risk.

GETTING A GRIP

JV Boards have a lot to do – and actively managing non-Board committees should not be one of them. But JV Boards do have a responsibility for ensuring the integrity of the overall governance system, which includes having an up-to-date understanding of committees and working groups.

How do Boards keep tabs on – and when needed restructure – committees? It starts

with some probing questions and, depending on the answers, may flip into a more

formal review.

Probing Questions

At a minimum, Board members should periodically ask some basic questions about committee set up and activities, including:

- Do we really know how many committees and working teams there are today, and how many people are spending how much time?

- To whom is each committee accountable – the Board, the CEO, or somewhere (dangerously) between the two?

- What exactly are these committees expected to do – provide added assurance to the Board, help management to succeed, or do something else? How is each committee doing relative to its fundamental objectives?[4]Committees, and the charters that define them, often overlook this concept of “fundamental objective.” We’ve found that Committee Charters tend to clinically define a committee’s roles and … Continue reading

- Do we have a good sense for how much – and what types of – information and other requests each of these committees is asking management to give them, and whether these requests are necessary?

- While these committees may not have any formal decision making authority, do they have informal authority – for instance, because the Board expects the committee’s “endorsement” prior to it reviewing certain management proposals?

- Do all committees still need to exist – or are there different mechanisms (e.g., audits, peer reviews, secondees, informal peer networks, asset managers) which would better fulfill the shareholders’ goals? What would happen if we disbanded certain committees – would we really lose some needed level of transparency, expertise, and the like?

Formal Reviews

When a Board is getting insufficient answers to such questions – or when the JV simply has a large number of committees – it may make sense to conduct a more formal review. Consider how two JVs did this:

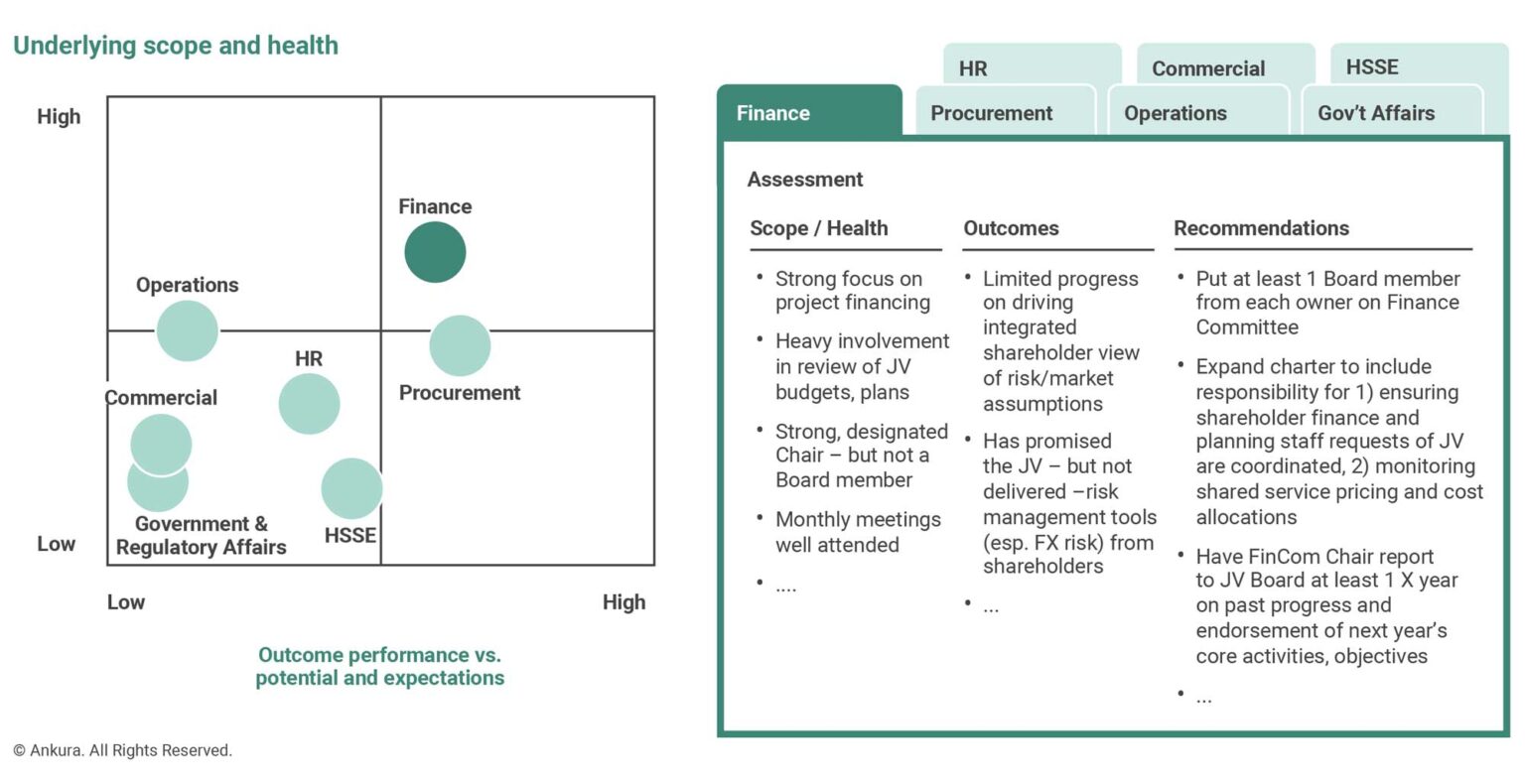

- Natural Resource JV: As part of its Annual Shareholder Audit, the Board of a large downstream oil JV periodically includes an evaluation of its half-dozen or so non-board committees – operations, technical, commercial, finance, government and regulatory affairs, etc. When the Board first commissioned this analysis a few years ago, it found significant variance in how the committees were meeting basic performance and process expectations (Exhibit 6). This analysis led to a fact-based discussion and a decision to “clean-up” the committees, including combining certain committees (e.g., operations and technical), discontinuing others (e.g., commercial and government affairs), and ensuring that the remaining groups had clearer mandates, greater clarity on their roles and pre-approval powers, and a direct line to the Board, via either participation of Board members on the committees, or regular reporting from the Committee Chair and JV President on the group’s activities.

The analysis also opened the Board’s eyes to a broader realization: that the shareholders had “bad governance posture.” As one Board member noted afterwards: “We were excessively invasive. Several of those committees saw their role as operating a parallel structure to management – but without any accountability. This was not only wasting shareholder resources – but also creating a drain on management, who had to deal with all sorts of data and information requests.” - Global Financial Services JV: A prominent new financial services JV aimed at creating a new product and technology platform for its owners recently agreed to bring in three new equity owners, increasing its owner group to almost a dozen. In light of the venture’s growing size and complexity, the Lead Directors from each owner sponsored a review of the governance and organization, including a look at the non-Board committees and working teams.

Exhibit 7: Proposed Restructuring of Committees and Working Teams

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

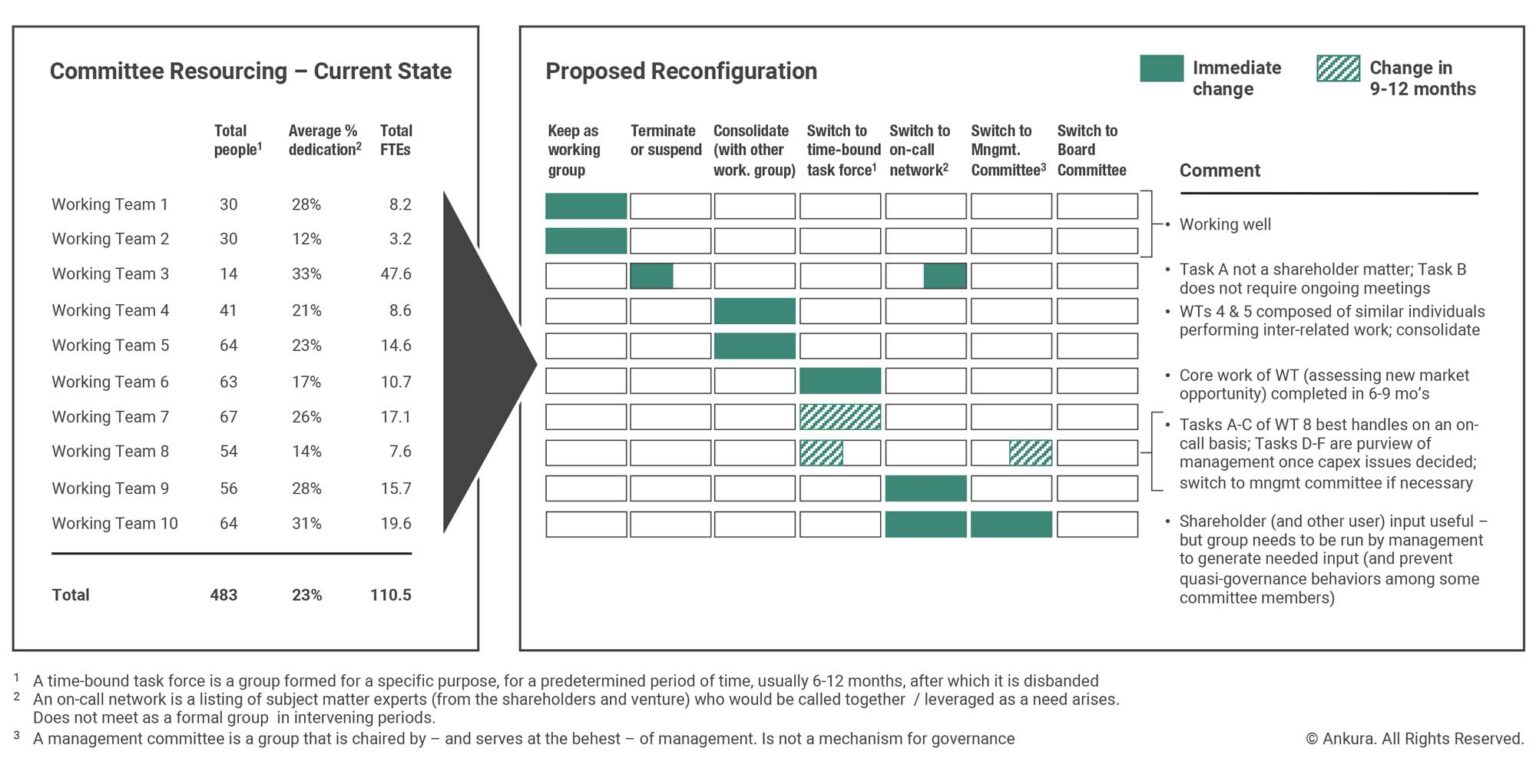

The results were eye-opening. In what was an admittedly extreme case, it turned out that more than 400 people across the 8 shareholders were involved in 10 different working teams (Exhibit 7). A typical working team member was spending 10-30% of his or her time on “committee work” – although almost none had any individual objectives or accountability related to their participation. “In other words,” noted one of the directors, “we had a plane load of ‘joint venture tourists’ who were flying all over the place to meet and talk, but were not on the hook for anything.”

Beyond sheer numbers, the Board also discovered that most of the committees had no consistent track record of impact. Based on interviews, an online survey, and other analysis performed by their alliance managers, the Lead Directors recommended a wholesale restructuring of committee configuration, reporting, and expectations of individual committee members. This included terminating certain committees, reclassifying others into temporary task-forces or peer networks, and setting certain minimum expectations of committee Chairs and members (e.g., that Chairs would be at least 25% dedicated and would have their role of committee Chair evaluated by the Board and their owner company).

WORKING GUIDELINES

Over the years at Water Street Partners and McKinsey & Co, we’ve worked with hundreds of JVs around the world. We’ve discovered that addressing issues related to committees can be an important lever in improving JV performance and underlying health – especially decision making speed, accountability, and alignment. In many cases, cleaning up committees can fundamentally change the level of enthusiasm that management brings to the job.

Based on this experience, we’ve arrived at some hard-learned lessons about how to structure and manage committees. We would urge companies to consider these ideas when reviewing existing JVs, or negotiating and structuring a new JV. For new JVs, some of these concepts deserve to be embedded directly into terms in the JV Operating Agreement; others might be included in Day One Board Mandates. For existing JVs, these might form the basis for a section within a set of Guiding Principles.[5]See, The Joint Venture Exchange, “Lighting the Way: Guiding Principles for Your JV,” June 2010.

The guidelines are:

- All committees shall report either to the Board (“Board Committees”) or to Management (“Management Committees”).

- Board Committee includes not only committees comprising Board members, but

also includes other owner committees and working groups that the owners have established to coordinate their activities and provide additional oversight into

specific functions. - The Board shall have direct visibility into the work of each Committee – whether that be through: one or more Board members participating directly in each committee; Board sign-off on each committee’s annual objectives and major activities; and/or periodic reporting to the Board on committee activities and performance.

- The Board shall designate itself or certain members (e.g., the Chair, Lead Directors, Executive Committee) to have formal responsibility for overseeing the portfolio of Board Committees. This responsibility includes periodically reviewing committee set-up, performance and health, and making recommendations to reflect the changing needs of the venture and its shareholders.

- Management Committees shall report to, and serve at the behest of, venture management, principally the JV CEO or GM.

- Board or Management Committee membership, on its own, does not come with unfettered or otherwise open access to venture management, assets, or information, nor to materials developed by management for the Board (e.g., Board pre-reading, presentations, minutes).

- Committee members do not speak for the Board, nor for Management – except in areas where the Board has delegated final decision authority to the committee.

- There shall be a Chairperson of each committee, who shall be accountable for its objectives and performance and for reviewing the contributions and performance of each committee member.

- No tourists or theatre critics: Committee members are expected to deliver benefits to the venture (e.g., insights, data, access to others within or outside their companies who could help the JV), in addition to performing other roles, such as helping coordinate with the other shareholders, etc.

- Committees should adopt different postures / modes of influence toward management, including: challenge, educate, assist, and applaud.

- Committees shall only be established when there is a clear and current need – and not in advance of a need.

JV Boards and CEOs cannot afford to take a passive approach to committees, working teams, and other governance fauna and substructures that may have grown underneath the Board. They are too valuable – and, if unmanaged, too dangerous – to be left without active supervision. So, to ask the question again: Are you tough enough to manage your committees?

Clint Eastwood, in his role as Dirty Harry, may have answered that question best: “Nothing wrong with shooting…as long as the right people get shot.”

Comments