APRIL 2021 — Managing a joint venture can be the most exciting job you will ever have, but it is also pound-for-pound one of the toughest jobs in business. As we watch the continuing stream of new joint venture announcements — whether that be Fiat entering into a new joint venture with Foxconn for electric vehicles, or Comcast pairing up with Charter Communications and ViacomCBS to take equal ownership of industry software platform Blockgraph — it is easy to see the allure of joint ventures in the eyes of those who will be asked to run them. After all, joint ventures often involve combining technologies, capabilities, and capital in novel ways, and JVs are usually instilled with exciting growth prospects. And joint venture CEOs and management teams are afforded a level of responsibility rarely seen in leadership positions within a business unit of the same size.

Enter your information to view the rest of this post.

"*" indicates required fields

But running a joint venture is difficult business – a job only for those who have the right stuff.

Indeed, many public companies have found JVs to be a useful proving ground for their own top leadership ranks. Recent chief executives of BP, Kvaerner, and LyondellBasell were all JV CEOs in the years leading up to their top appointments. Running a JV can offer persuasive evidence that an executive has what it takes to operate in a complex environment involving disparate stakeholders.

At BP, former CEO Bob Dudley fully forged his reputation between 2003 and 2008 when he was running the company’s massive Russian JV, TNK-BP – a hornets’ nest of shareholder misalignment that ultimately generated more than $40 billion in value for BP.

For every Bob Dudley, however, there is at least one spectacular flameout, and countless tours of duty cut short with disappointment. As the new JV CEO of a large, 50:50 JV told us:

“The last five CEOs were carried out on stretchers, and most were just dumped on the side of the street, left for dead or with careers that never recovered.”

The purpose of this note is to distill our experience serving hundreds of joint ventures over the last 20 years — and to offer guidance to JV CEOs and their teams on how to address the added challenges that JVs introduce.

The Added Challenge of JVs

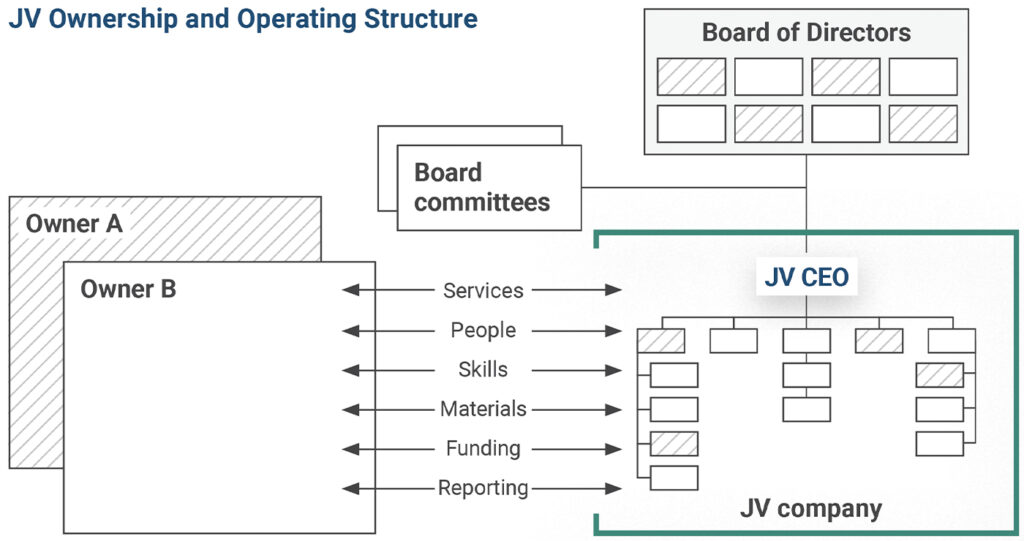

What does it take to run a JV? First is a recognition that the job of a JV CEO and management team requires all the capabilities needed to succeed in any ordinary business, plus the skills and tools needed to meet the added demands resulting from the shared ownership structure of joint ventures. These added demands are felt most acutely in five areas: Strategy, governance, shared services and operations, organization and talent, and finance and planning (Exhibit 1). In strategy, for example, a joint venture CEO must steer the business to meet the needs of the market and the needs of multiple owners – owners that often hold differing objectives, investment and risk preferences, views on which products and markets to prioritize, and how the JV should evolve.

Exhibit 1: Added Challenges of JV Management

| Added Challenges of JV Management | |

|---|---|

| What makes being a member of a JV management team significantly harder than running a similarly sized, wholly-owned business unit? | |

| Strategy | Strategy must be shaped and positioned to reflect the needs of the market and the needs of multiple owners – which, by the way, often have different objectives, investment and risk preferences, and views on which products and markets the JV should prioritize, how the JV should evolve, etc. |

| Governance | Governance must be run effectively with Board Directors who have structurally conflicting interests, varying level of experience, and different styles and interpretations of how involved they should be in steering the business – and who are usually prone to high turnover |

| Shared services and operations | Business operations must be optimized despite the JV’s dependencies on the owners along the value chain – as customers and / or suppliers, or as providers of key services, technology, assets, and / or infrastructure – which limits managerial freedom, and introduces asymmetric relationships with the owners, conflicts of interest, commercial complexity, etc. |

| Organization and talent | A strong and cohesive organization must be built from staff drawn from different corporate cultures, despite incomplete authority to manage owner secondees, and structural challenges of attracting and retaining top external talent given the JV’s constrained business scope, financial upside, and career headroom, and the tendency of shareholders to overreach |

| Finance and planning | Metrics and targets must be designed and agreed-upon that reflect the owners’ different goals and preferences, and account for all of the value created for the shareholders by the JV (beyond its P&L) The potentially high volume of owner (including non-Board member) reporting and information requests must be managed effectively |

| © Ankura. All Rights Reserved. | |

Second is a willingness of management to take on these challenges, and not wait for the Board to solve them. While all of these issues relate to the shareholders – and therefore are not fully within management’s delegated authority or control – strong JV CEOs and management teams catalyze discussions, shape solutions, and help the shareholders resist some bad behaviors that are detrimental to the businesses. This is not to say that a JV CEO can or should do this alone, or that the Board has no responsibility. On the contrary, the Board as a whole – and the Chair or Lead Directors in particular – must set the frame and create an environment where JV management can create solutions to these challenges.

Make no mistake: There are real consequences, both business and personal, for JV CEOs and management teams that do not meet these added demands. JVs that fail to meet these challenges tend to stall, under-delivering on their potential, and on the owners’ financial and operating objectives in forming the JV. In addition, JVs that discount these challenges may expose themselves – and their owners – to elevated levels of risk with regard to safety, health, environment, and reputation.

More personally and insidiously, a failure to respond to these JV-specific challenges can lead to chronic misalignment among owners, and shareholder overreach into the venture – creating a “tax” that can easily lead to management team members spending 30 to 35% or more of their time responding to shareholder-related matters, rather than operating the JV. For JV CEOs, the challenge of managing the shareholders cascades into deep frustrations across the management team, undermining productivity and professional satisfaction, increasing turnover, and making it harder to recruit new talent.

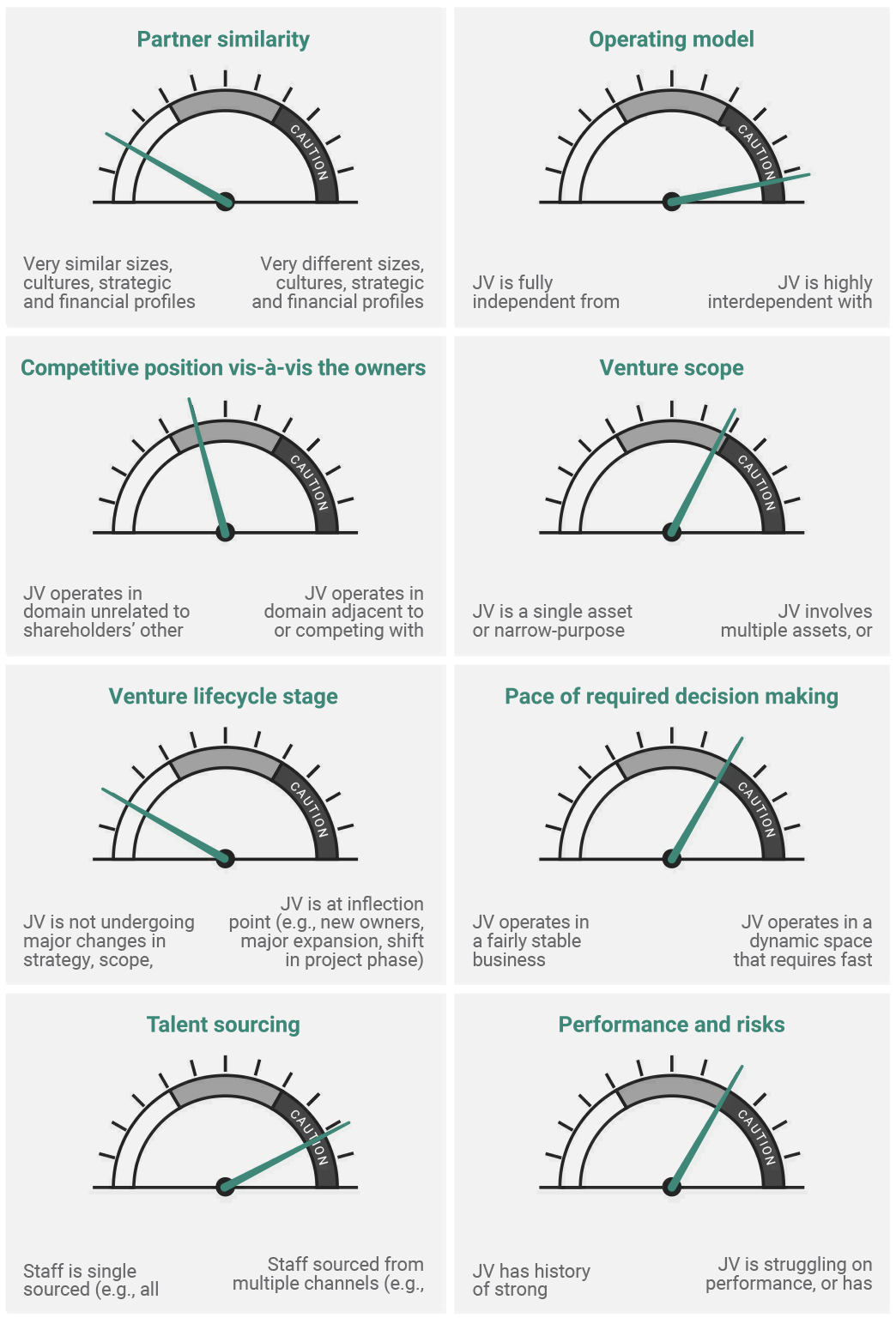

The extent to which any particular JV will face these added challenges varies based on the relationship between the JV’s shareholders, the extent to which a JV is independent, the cultural similarities or differences between the partners, and the venture’s scope, performance, and other factors (Exhibit 2). For example, the management teams of long-standing, highly independent ventures with similar partners (such as Exxon Mobil and Shell in Aera Energy) may face some added JV challenges (e.g., governance and aligning on growth), but, generally, these are fairly limited. The same can be said for the typical production-phase asset joint ventures in the oil and gas, mining, and chemicals industries that are operated by a single partner, and thus much less susceptible to owner-related complexities.

Exhibit 2: Gauging the JV Challenge

*Interdependence can be related to shareholder-provided services, seconded staff, shared-use assets and infrastructure, common systems and processes between the JV and shareholders, etc.

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

Contrast this with, say, joint ventures like Tesla-Toyota, Walmart-Bharti, or TNK-BP – ventures that assemble partners with radically different corporate cultures. Or compare this to JVs like Merck-Schering, Starbucks-Pepsico, Airbus, and Kashagan – ventures that, at different times, have depended extensively on their parent companies for technology, services, and infrastructure along the value chain, and have needed to orchestrate a web of operational interactions with the owners’ internal functions and other businesses. Or compare this to Star Alliance, a 27-partner global airline alliance, where the alliance’s activities are woven into virtually all of the operating functions of its owners – including the product, network planning, technology, maintenance, purchasing, branding, and customer service functions.

While a JV will not face all of these added challenges at any one moment, the presence of any of these challenges is enough to undermine the success of the mission. Below, we outline the five functional areas where the added challenges of JVs are felt most acutely and illustrate some of the ways that JV CEOs and management teams can address them.[1]Beyond these five functional areas, there are a set of cross-cutting themes – including launch and integration, alignment and stakeholder management, and restructuring and evolution – that are … Continue reading

Strategy

The Challenge

JV CEOs face two distinct issues in shaping JV strategy. First, the parent companies may not be aligned with each other – or internally – on the strategy for the JV. For instance, one parent may want the JV to grow into new markets or products, while the other parent may view those arenas as possible avenues for its own growth. In this case, the JV is blocked from pursuing those opportunities, despite the fact that neither parent is acting to pursue them. Or one parent may see the JV as “captive” (i.e., focused on serving its needs as a customer), while the other parent may see the JV as an independent entity that should be truly oriented toward serving the market, not just its owners. For example, the CEO of one European financial services JV proposed an ambitious strategy to the Board, which was supported by rigorous analysis, and which showed that the JV had an opportunity to capture a critical market in mobile payments. Although one of the parent companies was highly supportive, the strategy was nixed, because one parent wanted to pursue that opportunity on its own.

Second, JVs often do not have fully endowed strategy capabilities. There often is not a strategy unit within the JV, leaving the CEO and perhaps the CFO and/or a solo Head of Strategy to do the work. The JV’s strategy process often consists only of preparing for a Board offsite in the summer, where perhaps three hours per year are spent discussing strategy. As a result, “strategy” is often reduced to getting answers from the Board regarding specific growth proposals put forward by the JV management team. It is not a surprise, then, that many JV CEOs are frustrated by their inability to get approval to pursue obvious opportunities.

Some Solutions

Successful JV CEOs deploy a number of approaches to addressing these issues, including:

- Run a strategy process that is highly tuned to the shareholders. JV CEOs need to enter into the strategy process with eyes wide open regarding the degree of difficulty imposed by a terrain demanding multiple shareholders to align on the path forward. Practically, what this means is that the proposed strategy must be built on a structured and rigorous assessment of the market and competitive landscape, because the logic and analytics will come under intense scrutiny from the Board and shareholder organizations. Beyond this, the CEO needs to run a process that explicitly incorporates thinking about the shareholders (i.e., their corporate strategy, interests, and sensitivities). The process requires the skills of an international peace negotiator – knowing how and when to introduce ideas, being able to read various factions, knowing how to gain agreement on principles, and when to push for an up-or-down vote on the full strategy. We have found that JV CEOs are often better off not approaching important strategy and investment discussions with a “big bang” approach (i.e., unveiling a radically new strategy in one go, and leading the conversation with the answer). A better approach is to initially test concepts, gain directional agreement on preferred options (and the process for reaching final agreement), and then seek approval of the proposed strategy in a later conversation.

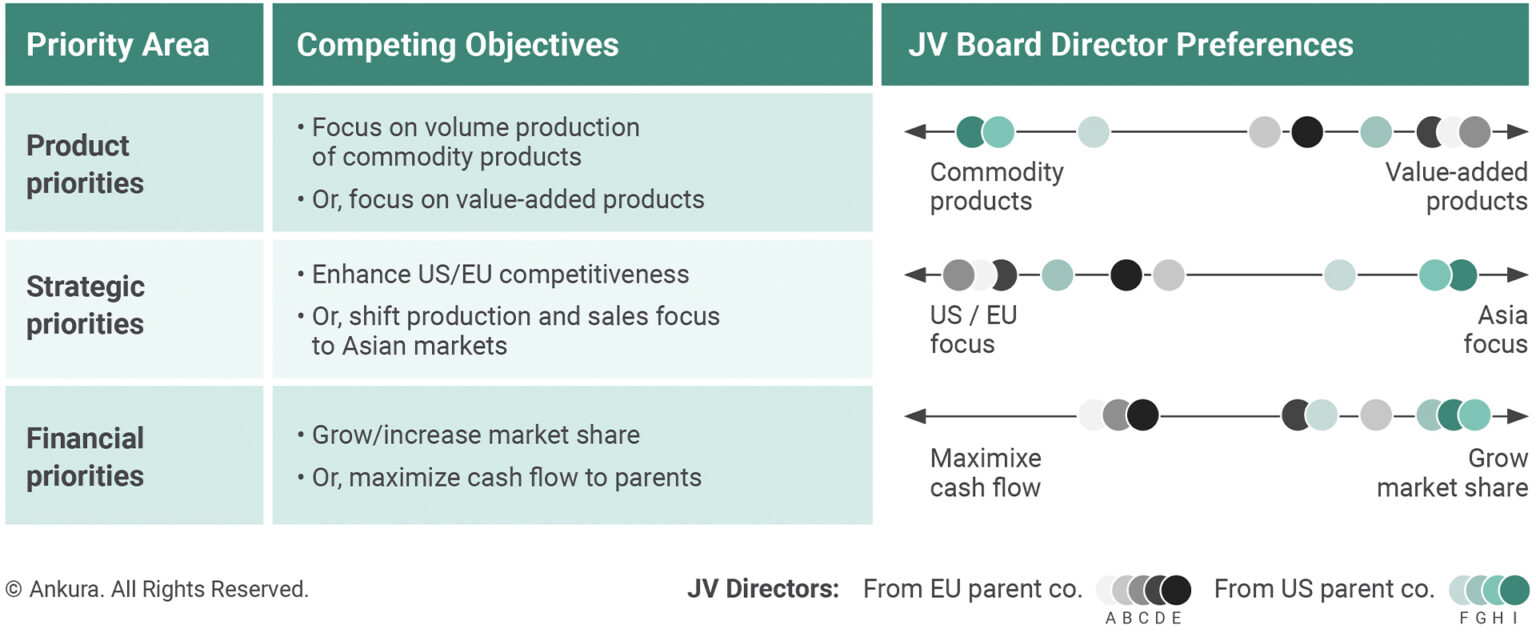

- Use Board surveys to test – and increase – Director alignment. For example, when such a tool was deployed in a chemicals venture between a U.S. and European partner, it showed the European Directors preferred that the JV focus on value-added products, while the U.S. Directors wanted the CEO to prioritize commodity product volume (Exhibit 3). The survey also revealed that the Board Directors from the European parent were more interested than the U.S. Directors in having the JV pursue opportunities in Asia. When the CEO shared the survey output with the Board, it prompted an in-depth Board discussion about the JV’s objectives and helped to align the Directors on metrics.

Exhibit 3: Clarifying the Owners’ Strategic Wants

- Use a strategy to identify markets that are in-scope, ruled out, or gray areas. By clarifying the JV’s strategic boundaries, the JV management team gains confidence about permissible growth arenas prior to developing in-depth strategic plans.

- Develop an M&A strategy. Such a strategy should include rationales for acquisitions, indicative targets, and specific acquisition offer ranges – and this M&A strategy should be tested with the Board when the broader JV strategy is being discussed. Aligning the shareholders on an M&A strategy for the JV in advance of an actual acquisition can reduce the chance of delays in approvals coming from two or more parent companies.

Governance

The Challenge

To do their jobs, JV CEOs need a governance system that works. A high-performing JV Board, for example, must do the same things as a corporate Board – i.e., shape and approve a strategy, take major investment decisions, monitor business performance, ensure that a high-performing top team is in place, and manage risk. But JV Boards must do far more, including clarify what the shareholders want from the venture, help the JV to access resources from those shareholders, and resolve shareholder conflicts.

For a host of reasons, this is not easy to achieve in a JV. For starters, most JV Directors are senior executives with demanding day jobs in their respective shareholder companies. It is no surprise that our benchmarking shows that the median JV Director spends just eight days per year fulfilling their Director duties, making it difficult and time consuming for JV CEOs to get needed attention. Furthermore, JV Boards are prone to high turnover – the median Director tenure is just 30 months – which creates demands on management to understand the styles and issues of new Directors, and to educate them on the business and their roles. At the same time, many JV Directors have structurally conflicting interests in the business (e.g., responsibility for managing parent company businesses that are adjacent to, or directly dependent upon, the joint venture). JV Directors also bring varying levels of experience in the JV’s markets and operations. Some have extraordinarily detailed understandings, while others have limited or no experience – which makes it difficult to have efficient Board conversations. Meanwhile, few JV Directors have had experience as CEOs or corporate Directors – roles that provide a basis for understanding how the CEO-Director relationship needs to differ from that between the head of a division and their direct report.

Relatedly, and perhaps most notably, JV Directors (and their shareholder companies) tend to bring different interpretations of how involved they should be in governing the JV. In most JVs, the natural posture of at least a few Directors is to lean forward – and to individually instruct the JV CEO or management team as if they were a direct subordinate. As one JV CEO told us: “It is fine to have one boss, but a wholly different matter to have multiple bosses, each of whom is from a different company, telling you very specifically what to do.”

Is it any wonder that governance is such a bugbear in joint ventures?

Some Solutions

Alone, JV CEOs cannot solve all the challenges of JV governance. After all, fewer than 5% of JV CEOs are even formal members of the Board, much less able to control that group. In fact, the Board Chair, or a senior Director from one of the parent companies, is the more natural owner of making the governance work. That said, because few JVs have instituted regular governance reviews, and because JV CEOs feel the dysfunction of governance far more acutely than do Board members themselves, JV CEOs are often the ones who, with the help of the Chair and/or Lead Directors, need to trigger a process to revisit governance. How can JV CEOs do this?

We suggest that JV CEOs start by focusing on four things:

- Take a strong position with the Board from the very beginning on the importance of good governance. This means communicating the clear link between governance and overall JV performance and risk management, driving an annual conversation with the Board about governance health, and supporting the Chair in conducting the right types of governance assessments. (Such assessments include governance system reviews, Board and committee assessments, and individual Director self-assessments.)

- Orchestrate a conversation with the Board about how it wants governance to work. This conversation should include defining how closely the Board wants to be involved in what issues – and memorializing this in a set of Guiding Principles, a Board Book, or other corporate governance policies.

- Take a more active role in defining what skills and attributes the JV needs on the Board. Most JV Agreements grant the shareholder the sole right to appoint Directors to fill its allocated seats on the Board. The unmanaged course is that the shareholders will fill the Board without an adequate eye to what skills and attributes the venture needs, which can accentuate skills gaps, or create other issues (such as mismatched expectations on time commitment from new Directors). By communicating these needs to the shareholders before they decide which executives will replace Directors rolling off the Board, CEOs and their teams can help ensure that the JV gets what it needs from the Board.

- Deliver on management’s end of the governance bargain by maintaining exceptional hygiene around Board meetings. This includes the development of an annual Board calendar and meeting agendas; advance distribution of succinct, well-prepared Board materials; maintenance of a Board action log and minutes; and the drafting of post-Board meeting communiqués to the shareholder organizations.

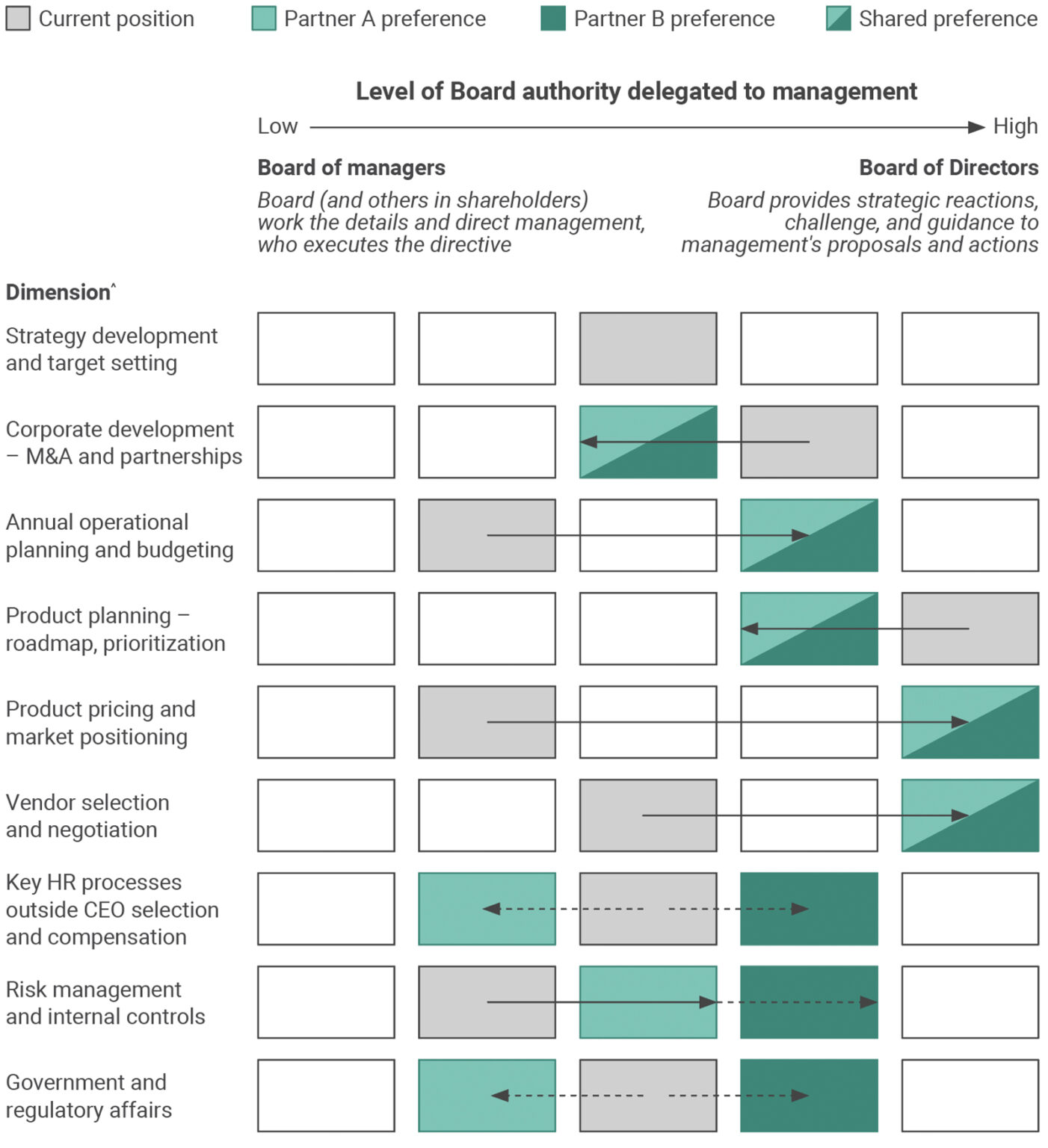

To bring some of these actions to life, consider the CEO of a U.S. healthcare technology joint venture. Concerned that certain Board members and others in the parent companies were reaching too far into the business – and thus undermining the venture’s competitive speed, management’s motivation, and CEO accountability – the CEO suggested (with the support of the Chair) that the Board initiate a structured conversation about how extensively the Board wanted to be involved in various dimensions of governing and managing the business. A series of individual conversations led to an initial mapping of views on where the Directors thought the JV was today – and where they thought the Board should be in the next couple of years – on such dimensions as setting the JV’s strategy, developing acquisition and partnership opportunities, and shaping the annual operating plan and budget (Exhibit 4).

Exhibit 4: Clarifying the JV’s Board Posture

* Based on Board member interviews and survey.

^ Not all dimensions shown (typical JV Board posture map includes 10 to 20 dimensions).

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

This map then served as the basis for a highly productive conversation among the Board, leading to a consensus that the Board needed to shift from a “Board of Managers” (that was heavily involved in many aspects of the business) toward something closer to a “Board of Directors” – at least on matters like annual planning and budgeting, risk management, vendor selection and negotiation, and product pricing. Interestingly, the map also revealed areas – such as acquisitions – where the Board wanted to be more involved.

This led to a request for management to provide a regular update to the Board on acquisition and partnership opportunities (targets and discussions), and to engage a “deal advisory steering group” composed of three non-Board senior dealmakers in the owners when JV management entered any negotiations on a material transaction. The map also highlighted the areas where the Board Directors were not aligned – such as on government affairs and human resources oversight – prompting a discussion that started to bridge these differences.

The JV CEO, with ongoing engagement from the Board, then converted this dialogue into a set of Guiding Principles (Exhibit 5) that clarified how the Board collectively wanted governance to work. The CEO cascaded these principles into other targeted improvements to governance (including a re-purposing of committees and shareholder assurance processes), put in place a post-Board meeting communiqué, and imposed greater discipline around Board material preparation, Director onboarding, and pre-Board one-on-ones with individual Directors.

Exhibit 5: Guiding Principles

| Sample Guiding Principles | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Operate the JV as an independent company – own people, processes, etc. |

| 2 | Remain open to new companies joining as owners – provided they are like-minded and bring revenue |

| 3 | Provide the owners, as major customers, with early input on the overall technology and product roadmap |

| 4 | Structure owner pricing so that the JV is self-funding, with sufficient retained earnings to fund strategic initiatives |

| 5 | Govern the JV through the Board; the CEO reports solely to the Board collectively |

| 6 | Limit the number of owner committees |

| 7 | Ensure that the Board has a strong independent perspective, and does not reflect only owners’ views |

| 8 | Hold the CEO accountable for the business – consistent with a company of its performance, risk profile, and age |

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

Shared Services and Operations

The Challenge

The ideal JV, from a JV CEO’s perspective, is one that is able to access the scale, resources, and capabilities of its shareholders without interference, friction, or hidden costs from those same shareholders.

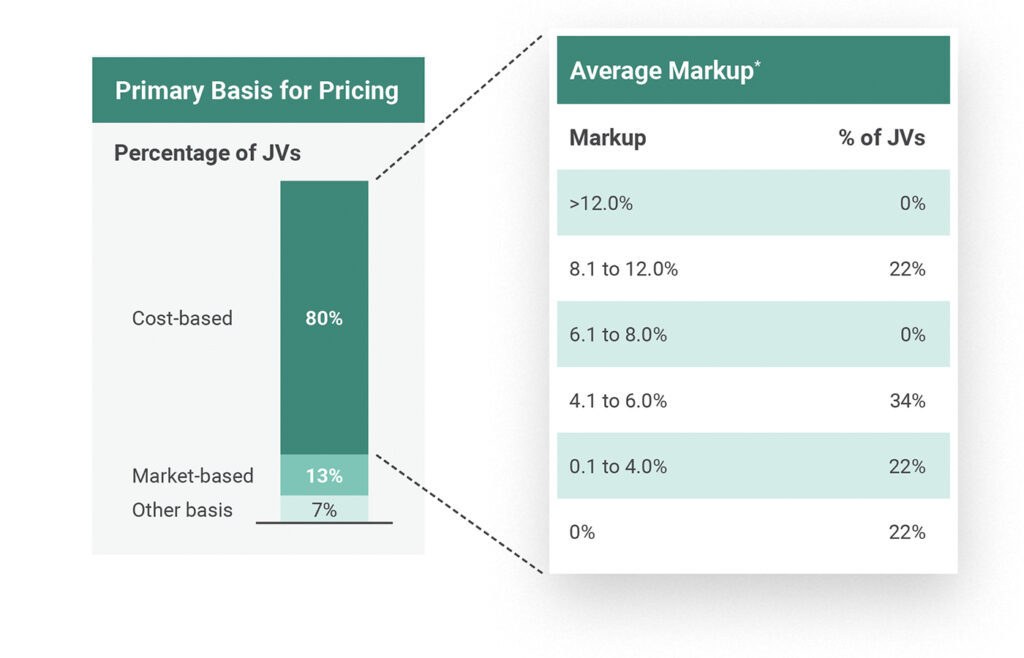

Our benchmarking has shown that 76% of JVs receive some shared services — typically finance, HR, or operations support – from the parent companies, with the prevalence and volume of such services even higher in JVs in their first few years of life (Exhibit 6). Cost-based pricing is the norm, and shareholder-provided services are usually not subject to external bidding or third-party benchmarking. This can lead to perennial frictions about specifications, responsiveness, and pricing fairness. This should not be a surprise. After all, service functions in large corporations are not set up to provide third-party services, and the needs of a new JV are often less complex – and lower in cost – than those of a multi-business, global corporation. Yet the JV has to pay the full freight of a large shareholder company under a cost-allocation shared-service regime.

Exhibit 6: Shared Services in JVs

N = 27 JVs

| Summary benchmarking data | Metric |

|---|---|

| Value of shared services provided by parents (annual spend, median) | $30 million |

| Shared services as percentage of JV operating budget (%, median) | 6% |

| Highest usage by industry by percentage of JV operating budget (industry, median) | Chemicals (13%) |

| Highest usage by operating model as percent of JV operating budget (operating model, median) | Single-partner op JVs (44%) |

| Highest usage by JV age as percentage of JV operating budget (range, median) | 3 to 10 years (7%) |

| Categories of shared services used by most JVs (categories, percentage of JVs using) | Ops, Finance, HR (76%) |

| Largest category of shared services by value (defined as annual spend by JV on purchases from parent) | IT / Telecom |

| © Ankura. All Rights Reserved. |

*For cost-based JVs, average percentage markup beyond fully loaded costs for largest shared service category by spend

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

Even more challenging is when JV Directors wear two different hats – as Board members, and also as customers of or suppliers to the JV. In these cases, the JV management team often faces the challenge of differentiating between owner guidance and customer demands.

Some Solutions

Solutions to services and parent operational interaction issues that have been successfully used by JV CEOs include:

- Map the JV’s value chain. A value chain analysis is a powerful tool for helping JV CEOs and their Boards understand and communicate how their joint venture actually works – and to identify needs, risks, and gaps in how it interacts with the shareholders at an operational level. In its simplest form, a value chain map depicts, on one page, the integrated set of activities – for instance, stretching from research and manufacturing, to marketing, sales, and distribution – that the venture requires in order to bring its offering to market. Unlike a value chain map of a wholly-owned business, however, a JV value chain map explicitly calls out those activities provided by the shareholders, and the interfaces with them. This picture can thus serve as a basis for the JV CEO to conduct a structured conversation with the Board about who does what work, for whom, at whose behest, and on whose systems – and how this picture needs to change or be clarified over time. In one JV, the volume of shareholder-provided services was reduced by about two-thirds over a five-year period, leading to substantial cost savings for the JV as services were simplified to meet the needs of the venture.

- Agree on a set of shared service guiding principles. Explicitly defining the degrees of freedom that the JV has to purchase, change, negotiate, or direct services or input transactions with parent companies can save the JV management team major headaches down the road. Also beneficial is agreeing on what issues are Board or owner matters, versus which are customer or supplier matters – and defining different forums and decision-making processes for each.

- Establish total transparency around shared services. This should include what services are provided by whom, how much they cost, and the process for providing feedback on quality of service.

- Establish guidelines and a framework for service pricing. We have benchmarked shared-service agreements extensively and have found that a range of cost plus 0 to 6% is the most common pricing standard – although we would advocate for market pricing where feasible.

- Create an oversight process that includes a Board-level annual review of shareholder-provided services. Such a review ensures that the disinterested (i.e. non-service-providing) JV partners are able to have sufficient view into the quality and pricing of services provided to the JV by their partner – and avoids putting JV management in a position of having to negotiate with an owner.

- Create a service-delivery organization within the JV, including incentives. A dedicated unit for managing services ensures that there is a “single necktie to choke” in terms of accountability. This accountability can be enhanced by building incentives into the variable compensation of people who staff this service-delivery unit, as well as those in the parent companies who are providing critical services or inputs to the venture.

Organization and Talent

The Challenge

JVs introduce a number of unique talent issues. One is attracting and retaining talent. For example, a small media JV struggled to recruit and keep high performers because they preferred the wider and less risky career opportunities provided by the global parent companies. A second and related challenge is that JV compensation can be biased downward by as much as 50 to 250% – by not adequately reflecting the complexity and risks of the business. A third challenge is aligning diverse cultures. One new CEO of a cross-border JV discovered that “the JV was like a dysfunctional family, where separate cultures and executive infighting is the norm.” Additionally, JV CEOs struggle at times with clear accountabilities across their teams, especially when secondees are part of the talent pool. For instance, the JV CEO of an emerging market JV could not fire a senior manager (despite his clear underperformance) because the manager reported up through a local parent company that refused to remove him.

Some Solutions

To overcome these and other talent related issues in JVs, we recommend that JV CEOs follow these best practices:

- Clarify management accountabilities and reporting relationships – and get the endorsement of the Board. Standard JV Agreements, JV CEO job descriptions, and delegations of authority matrices do little to clarify how talent will be managed within a joint venture context. The best JV CEOs clarify these issues in a set of talent Guiding Principles – guidelines that frame the JV’s approach to talent sourcing and selection, reporting relationships, secondee loyalty and communication, and succession planning. In one financial services JV, the CEO used such principles to clarify which talent matters were within the purview of management (which included performance reviews and ratings for all direct reports, including secondees; individual compensation decisions for all jobs; and organizational design and job scoping), and which were retained by the Board (final hiring authority for the CEO and CFO). The CEO also used the principles to establish – in writing – that the CEO role reported solely to the Board as a whole, and not to any one Director.

- Catalyze a process to ensure that the JV’s compensation model adequately reflects the actual complexity and risks of managing the business. JVs often have compensation structures that underrate the risk and complexity of running the business, and therefore under-compensate the management team. What can CEOs do about this? For starters, CEOs can catalyze a conversation with the Board or Compensation Committee about the right compensation model for the venture. With Towers Watson, we conducted a first-of-its-kind study on JV compensation plans that found most JV Boards lack a sufficiently rigorous methodology to determine whether to pay JV executives in-line with business unit or independent company standards – a decision that can make a 50 to 250% difference in total individual compensation. To challenge unfair biases, a JV CEO might ask the Board to consider the perspectives of a JV-experienced compensation expert. When we have been part of these conversations, we have leveraged a tool developed with Towers Watson that scores the complexity of a joint venture – as measured by its customer profile, business system scope, governance structure, economic structure, and staffing model – and recommends whether the JV’s compensation peer group should be filled with business units, independent companies, or a blend of the two.

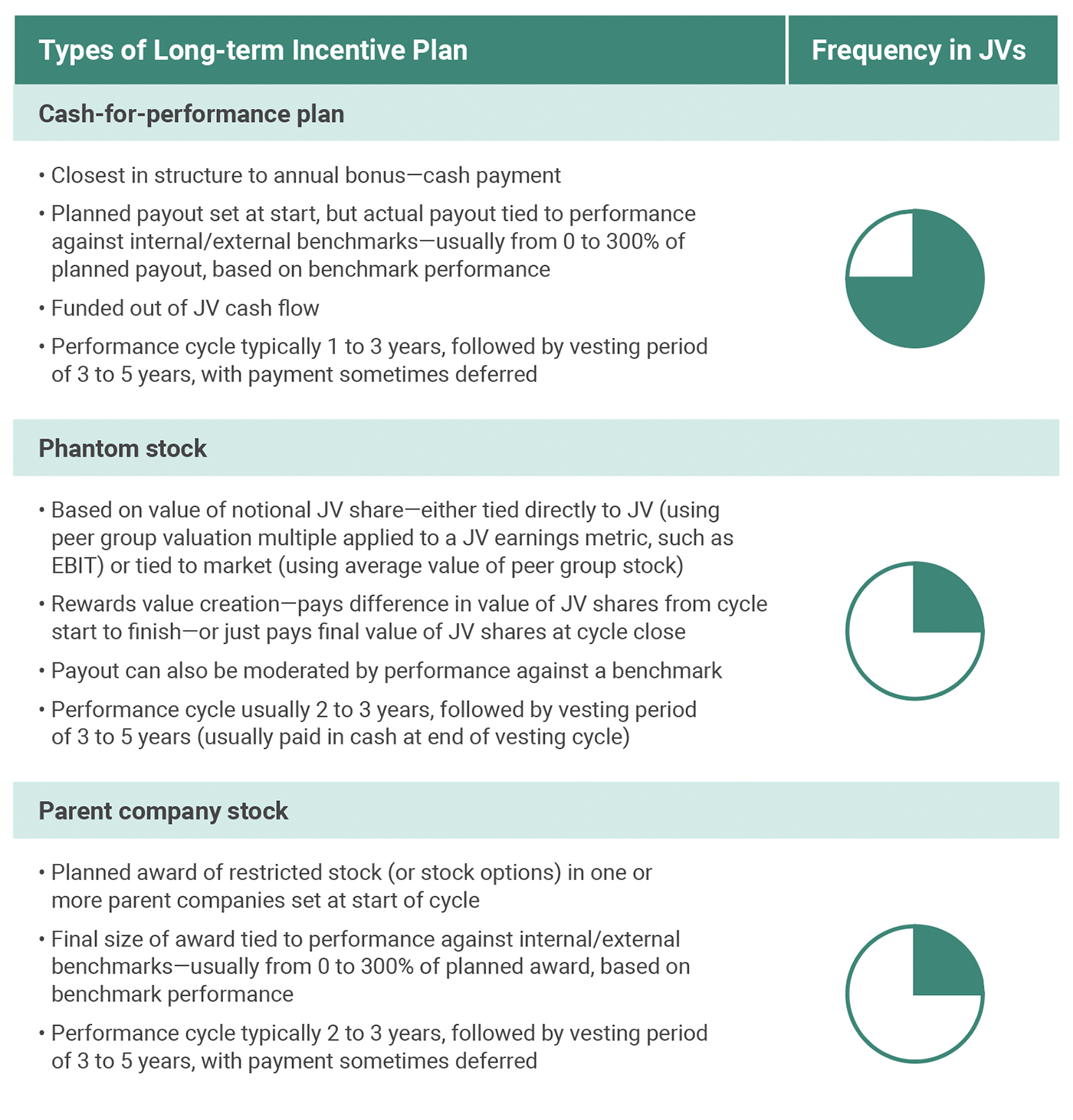

In addition to thinking broadly about compensation benchmarks, CEOs should help shape the right long-term incentive plan (LTIP) for JV employees. While most JVs use a cash-based plan (Exhibit 7), our benchmarking shows that there are other, more creative LTIP approaches used in some JVs – plans that seek to synthetically replicate public company stock – and stock option-based plans that offer the potential for substantial wealth creation if the venture delivers extraordinary performance.

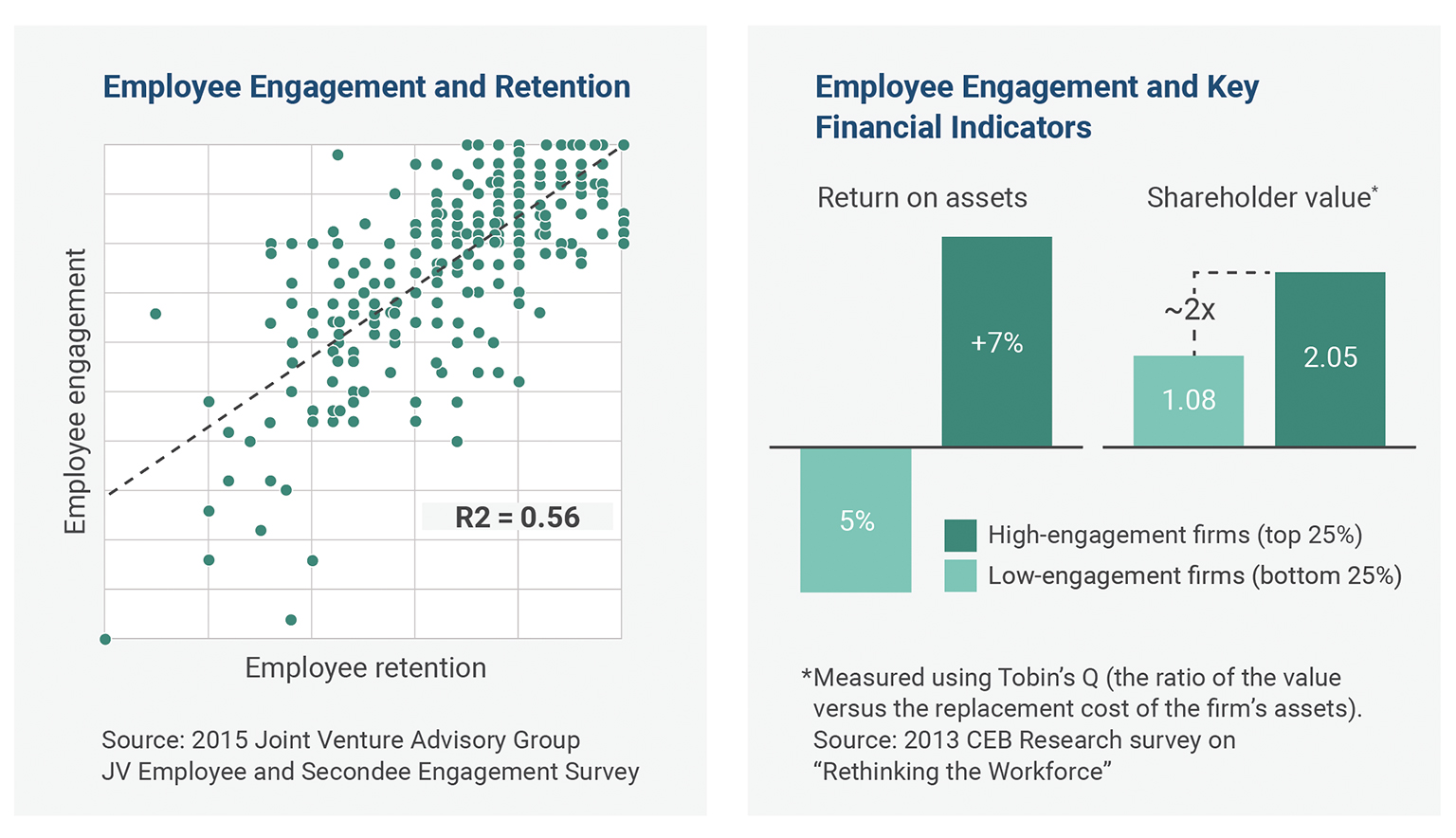

- Regularly monitor JV employee and secondee engagement. Calibrating the level of employee engagement and the health of corporate culture is a useful exercise in all companies – and JVs are no exception. A recent Ankura analysis shows that employee engagement in JVs strongly correlates with retention rates and business performance (Exhibit 8). To test engagement among their employee populations – which includes both direct JV employees and shareholder secondees – a JV CEO might consider using a survey instrument that we recently developed. Our employee engagement survey incorporates traditional analytics, as well as engagement factors that are unique to JVs (e.g., how interactions with the shareholders impact employee engagement).

The survey readout is an efficient way to independently – and accurately – take the pulse of the JV’s employee group, understand what is driving engagement, identify frustrations, and generate solutions.

For example, in a European energy joint venture, the analysis revealed that inconsistent messages from the shareholders – and the shareholders’ apparent challenges in resolving these misalignments – had a substantial impact on the engagement of employees in the JV. The JV CEO used this piece of data in a conversation with the Board, which led to a resetting of how the shareholders communicate with management, especially on the timing of and interest in potential capital investments. - Leverage development opportunities offered by the parents. JVs have a structural advantage when it comes to developing employees – but few CEOs use it. Because joint ventures are owned by two or more companies (which are often large, successful firms), JVs have the potential to leverage the parent companies in creative ways to develop JV talent. An analysis we conducted identified 28 specific ways that JVs are leveraging their shareholders to develop their employees. These practices range from having JV employees participate in parent peer groups, training programs, and operational reviews; to reverse secondments; inclusion of JV employees in parent company cohort reviews; and even the option for JV employees to re-badge as parent employees. One example comes from Swisscard, a 600-employee payments JV between American Express and Credit Suisse. In this JV, employees are transferred into a parent function (e.g., legal, marketing, risk) so that the JV employee can learn through observation and doing.

Finance and Planning

The Challenge

Peer inside the finance and planning department of a joint venture, and you will probably find it buzzing with activity – and angst. Our benchmarking has shown that JV finance departments are routinely 50 to 100% larger than those of similarly sized, non-JV businesses – and are still running too hot in terms of activity levels. This is explained by the demands of reporting on a wide variety of metrics, the accommodation of the different accounting systems and reporting calendars of the shareholder companies, a high volume of often ad hoc shareholder requests for information, and the demands of tracking and accounting for commercial transactions between the JV and shareholders.

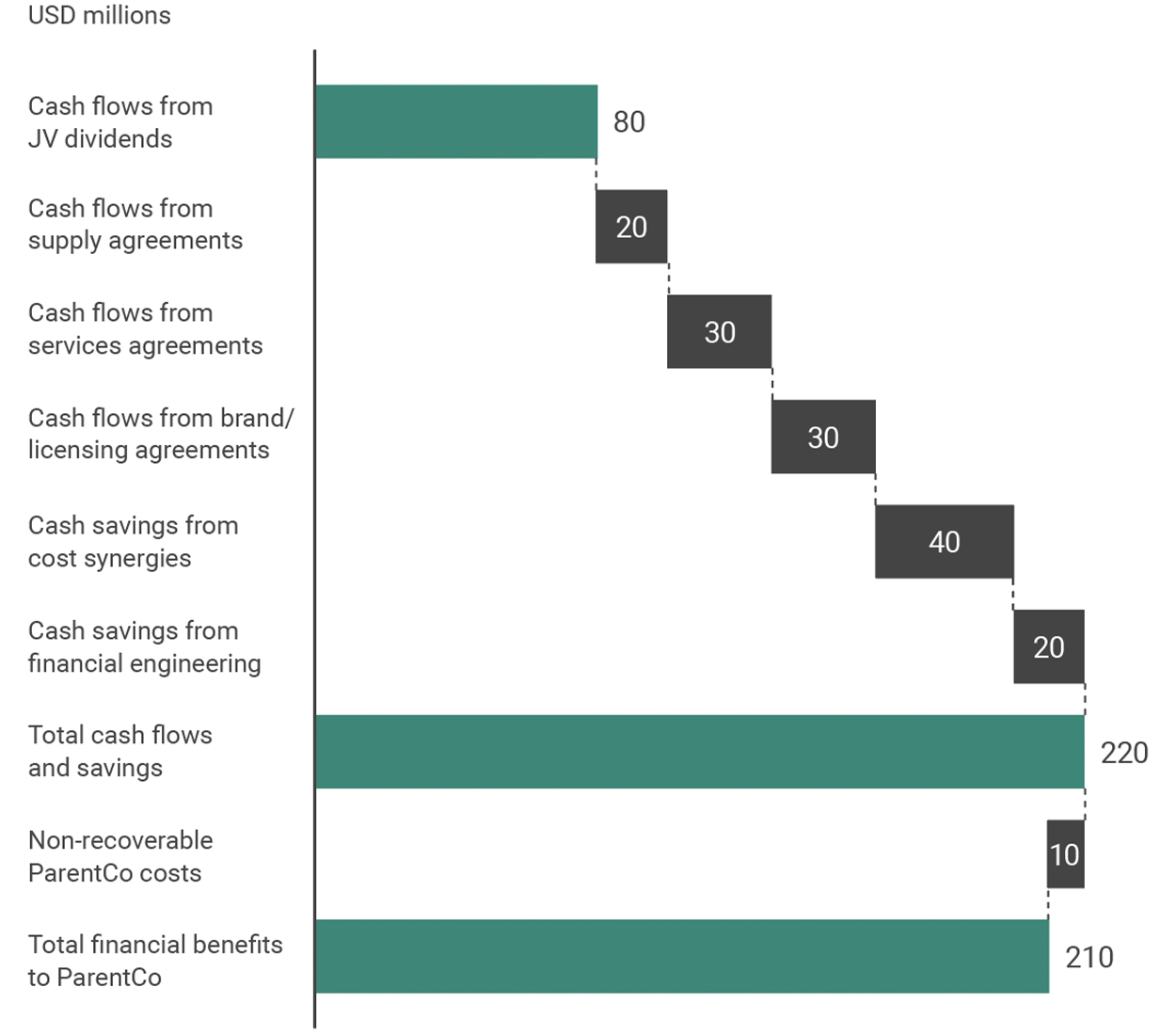

One especially tricky area is setting metrics and targets. In JVs, these scoring tools must be designed in a way that accounts for the owners’ different business goals and preferences, while also accurately reflecting what we call Total Venture Economics – the actual value being created for the shareholders by the JV, not just through its P&L. Many JVs – including Airbus, Star Alliance, and the vast majority of oil and gas, chemical, and mining ventures – operate under economic models structured such that a notable portion of the returns to shareholders are delivered through means other than dividends (e.g., via license and service fees, privileged supply contracts, and cross-selling opportunities with other shareholder products) (Exhibit 9). While this picture of Total Venture Economics is what ultimately matters to the shareholders, such non-P&L financial and strategic benefits to the shareholders are usually not tracked or discussed directly.

Exhibit 9: Total Venture Economics

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

A second finance-related challenge relates to handling the high volume of shareholder (including non-Board) reporting and information requests. It is all too common for the shareholder organizations to reflexively treat the JV as a wholly-owned operating unit, and to make all sorts of reporting demands and information requests. At our annual JV CEO Roundtable last year, the CEO of a 50:50 JV in the banking industry described how his team was subjected to endless stream of requests from functions inside the shareholders, each of which seemed to operate under the belief that they were an owner of the venture, and were therefore entitled to whatever information they needed. As the CEO described it, “My parent companies have a combined 260,000 [employees]. But I told my Board: ‘Let me be clear: I do not have 260,000 shareholders. I have two shareholders, and they have appointed eight executives to the Board. You are my shareholders, not everyone else.’”

Adding to the workload, a JV finance organization will often need to negotiate or finalize the details of commercial agreements with individual shareholders (e.g., for license fees, sales commissions, shared-use asset costs, shared-service cost allocations and charge backs, third-party debt guarantees), and audit and manage billing for these agreements. Not only does such work consume time, it is also scrutinized, and has the potential to be politically explosive.

Some Solutions

Successful JV CEOs deploy a number of approaches to address these issues:

- Expand financial reports to account for non-P&L revenues and costs accruing to owners. While certain owner economics may be closely guarded secrets (e.g., margins on shareholder-provided services), others may be known and sharable, or can be calculated based on some agreed-upon assumptions (Exhibit 10). Including such numbers alongside the JV’s standard P&L – and thus providing a more holistic view of the venture’s performance – can help drive alignment between the shareholders on core business objectives, and productively expose key drivers of shareholder behavior.

- Create a performance scorecard that is balanced and reflects what is going on in and around the venture. Beyond generating a holistic picture of the financials, a JV scorecard might usefully include leading indicators of venture health and performance.

For example, in a five-party financial services JV created to develop and operate a technology platform for communicating with and managing key customers of the owners and third parties, the JV CEO developed a scorecard, endorsed by the Board, that tracked owner satisfaction with the JV on key dimensions – technology and product development, sales, and customer service – where the venture needed to work in close consultation with the owner companies.

Exhibit 10: JV Shadow P&L

| Summary of Parent Company Financial Returns From JV | Parent A | Parent B |

|---|---|---|

| JV P&L income to owners | $ – | $ – |

| Share of JV dividends (based on ownership stake) | $ – | $ – |

| Other financial benefits (e.g., one-time payments) | $ – | $ – |

| Non-P&L financial benefits to owners | $ – | $ – |

| Earnings from provision of technology to JV | $ – | $ – |

| Earnings from provision of services to JV | $ – | $ – |

| Earnings from brand/licensing agreements with JV | $ – | $ – |

| Earnings from supply agreements with JV | $ – | $ – |

| Earnings from JV’s use/leasing of parent facilities | $ – | $ – |

| Earnings from interest on provision of loans to JV | $ – | $ – |

| Savings from shared-asset cost synergies with JV | $ – | $ – |

| Savings from pooled purchasing with JV | $ – | $ – |

| Savings from privileged pricing on offtake and/or | $ – | $ – |

| product purchases from JV | ||

| Other parent company non-P&L benefits from JV* | $ – | $ – |

| Total financial benefits to owners | $ – | $ – |

| * Examples of other benefits include: (1) earnings from JV pull-through sales of parent company products and cross-selling/bundling with JV products; (2) financial re-engineering benefits to parent company (e.g., de-leveraged balance sheet, capex avoidance, reduction in inventory due to JV presence, reduction in working capital); (3) value from broader relationship with other shareholder(s) developed through JV relationship. | ||

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

- Calibrate how much time your management team is spending responding to shareholder requests. One way to create more space for you and your management team to run the business is to simply dimension how much time is being spent responding to shareholder needs – and create a rough breakdown of what type of work for the JV is being generated by whom in the shareholders. For example, in a European pipeline JV, our analysis showed that management was spending 40% of its total time responding to the shareholders – preparing and refining materials for Board and committee meetings, responding to one-off information requests from shareholder functional groups, preparing answers to shareholder audit and assurance processes, etc.

By putting this data in front of the Board – and showing the location of the biggest time sinks – the CEO was finally able to get the Board to appreciate the costs of the shareholders’ heavy and uncoordinated involvement with the JV. As a result, the Board revamped the structure, role, and reporting relationship of various non-Board committees, and streamlined the shareholder audit and assurance process.

- Co-develop, with the shareholders, a standard monthly operations report. One of the numerous practices we have identified to streamline shareholder reporting in JVs involves the preparation of a monthly report (e.g., of 15 to 20 pages) assembled by JV management, that is based on the pre-specified and detailed reporting needs and formats of the shareholders. By pre-agreeing with the shareholders to a standard report format, including a table of contents, key metrics, calculation methodologies, data tables, and standard exhibits (e.g., major risks register, planned and actual budget, major variances, cost curve), a JV may be able to reduce by 90% or more the shareholder companies’ ad hoc information requests.

- Be careful what information you put in front of your Board. JV Board members – who often are experienced operating executives, but much less often are experienced Board members – have a natural tendency to engage and challenge whatever information is put in front of them, sometimes at a surprising level of depth. At a Roundtable we hosted in London, the CEO of a financial services JV recounted a moment at his first Board meeting, two weeks into his tenure, where a member of the management team presented a detailed technology roadmap and project team configuration picture of an IT project the JV was considering. “The Board members just dove straight in, and started challenging specific dates, functionality, resourcing levels, and team reporting relationships,” according to the CEO. “It was crazy. We weren’t even asking them to approve the project yet, and here we were in this conversation that was three levels too deep and wasting all this Board time.” As a result of this incident, the CEO manages much more carefully what information is put in front of the Board.

The potential rewards of successfully piloting a joint venture are enormous.

Those who can navigate the challenges – which at times can be considerable – should be a celebrated breed. Do you have the right stuff?