[Infographic] Independent Perspectives Prove Effective in Resolving JV Disputes

98% of disputes that have been referred to a dispute review board do not proceed to arbitration or litigation.

Alliances can be powerful creators of wealth – but come with no guarantee of success. Improving the odds requires a dedication to the art and craft of alliance structuring.

June 2016— PARTNERSHIPS HAVE COME of age in the last 20 years, becoming a central tool for corporate strategy and competitive advantage across industries and geographies. Companies as diverse as Amazon, Glaxo, Google, IBM, Microsoft, NewsCorp, Philips, Siemens, Shell, Starbucks, and Uber all routinely see partnerships accounting for 20-50% of their corporate value – whether measured in terms of revenues, assets, income, or market capitalization. Meanwhile, the proliferation of partnerships continues unabated; our analysis shows that the number of joint ventures and partnerships has grown every year since 2015.[1]See ”JVs and Partnerships in an Economic Downturn,” James Bamford, Gerard Baynham, and David Ernst, Harvard Business Review, Sep-Oct 2020.

Most of these collaborations are structured as non-equity alliances – i.e., purely contractual agreements where no new equity structure or separate joint venture company is created.[2]Some industries like oil and gas also rely on unincorporated joint ventures, where no new legal entity is created, and the underlying purpose, structure, and workings are different from joint … Continue reading

In fast-moving industries like software, electronics, financial services, pharmaceuticals, and retail, non-equity alliances are the dominant form of partnership. These industries thrive on purely contractual relationships that offer a fast way to access capabilities and markets without the time, rigidity, and other issues associated with creating a separate company with a counterparty. Indeed, individual non-equity alliances are often being structured as part of broader alliance ecosystems, where firms are assembling complementary and sometimes overlapping partnerships to introduce entirely new business models.

"*" indicates required fields

We are also seeing the continued drive of pharmaceutical, high-tech, retail, and other firms to “standardize” their approach to partnerships as part of their R&D, manufacturing, and/or and marketing strategies. At the same time, companies are enabling their alliances through various electronic collaboration tools and systems. Despite some new trends, several classic issues still arise when developing and structuring non-equity alliances. These include: Ensuring alignment on objectives; making sure that an alliance is the right structure; getting partners to commit the resources; coordinating interactions between the partners; getting partners aligned via mutually beneficial (though rarely equitable) economic outcomes; managing the partnership or ecosystem; and planning for the future if things succeed – or fail.

This insight introduces alliances in more detail, describes their benefits and risks, and shares our lessons-learned on effective alliance transaction structuring – including processes and key deal terms.

Alliances Defined. We define a non-equity alliance as a relationship between two or more companies, aimed at achieving a common objective by coordinating efforts, while each party retains its organizational independence, and no new equity entity or corporation is created.[1]Some companies choose to take a minority stake in an alliance partner as part of forming an operating alliance, in order to demonstrate commitment and increase alignment around joint value creation, … Continue reading Alliances bind supplier contracts, license agreements, distributorships, or sales agency agreements, but not as closely as forming a new jointly-owned company with consolidated assets, such as a joint venture (Exhibit 1).

The contracts underlying alliances typically spell out:

There are some key differences compared to equity JVs, though, that are not all intuitive:

Alliance Structure and Purpose. There are many types of alliances across the value chain (Exhibit 2). Some target a single part of the value chain (for example, to research and develop a new technology that each partner will be able to use in its own business), but others may be formed with an eye towards collaboration across the entire value chain.

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved

Each industry has its own unique terminology for alliances. The aerospace and defense industry talks about “teaming arrangements” to jointly bid on and deliver work. Pharmaceutical companies talk about “co-development” and “co-promotion” alliances. High-tech companies speak about “go-to-market” alliances when referring to sales and marketing partnerships. Regardless of what term is used to describe them, most alliances reflect one or more of the following purposes:

Some industries default to certain kinds of alliances precisely because they are common in the industry and thus well understood (Exhibit 3). For example, the pharmaceutical industry has used co-promotion (or increasingly, reverse copromotion) alliances since the 1980s to drive sales in new geographies, while the aerospace and defense industry has a well-grooved process for companies to jointly bid on and deliver government contracts via teaming agreements.

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

Most, if not all, of the benefits sought in an alliance also drive joint venture activity. This makes it strange that so many partnership discussions jump immediately to a joint venture. While an alliance often lacks the full synergy benefits of a highly integrated consolidation joint venture, it also introduces significantly less risk and complexity – sometimes leading to higher value creation overall.

We believe companies should consider JVs and non-equity alliance options alike before deciding on one or the other. Consider the example of a regional industrial systems manufacturer seeking a partnership to gain access to sales channels in new geographies.

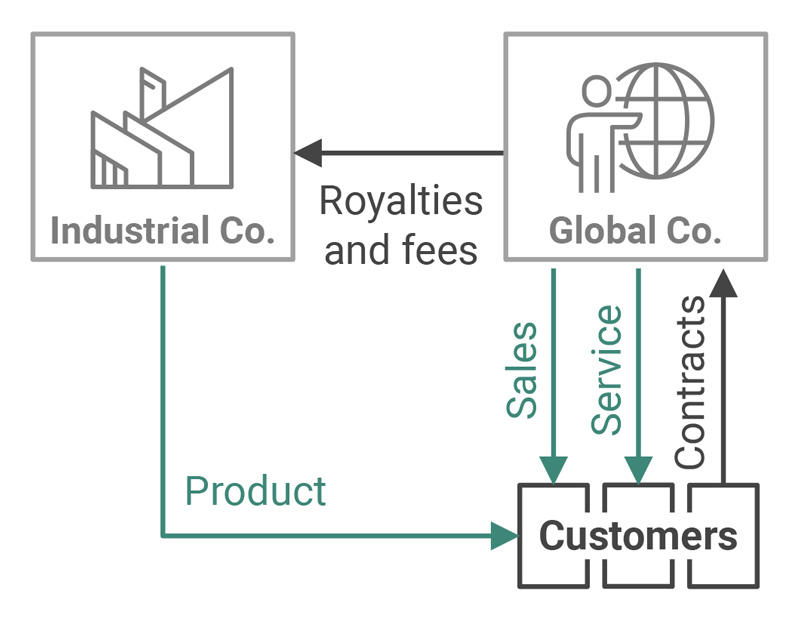

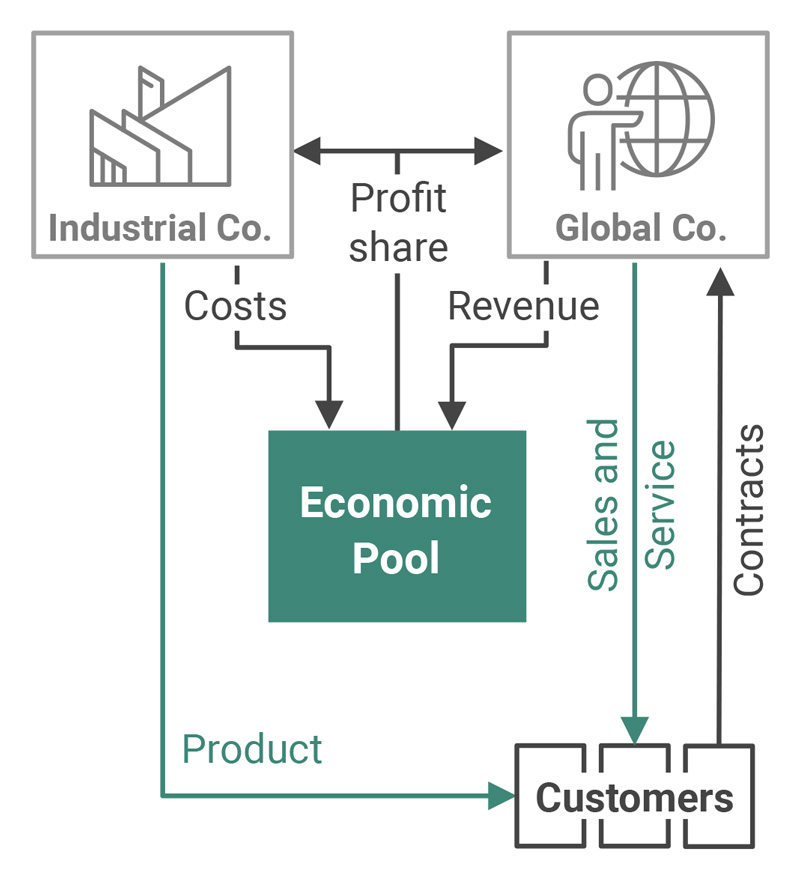

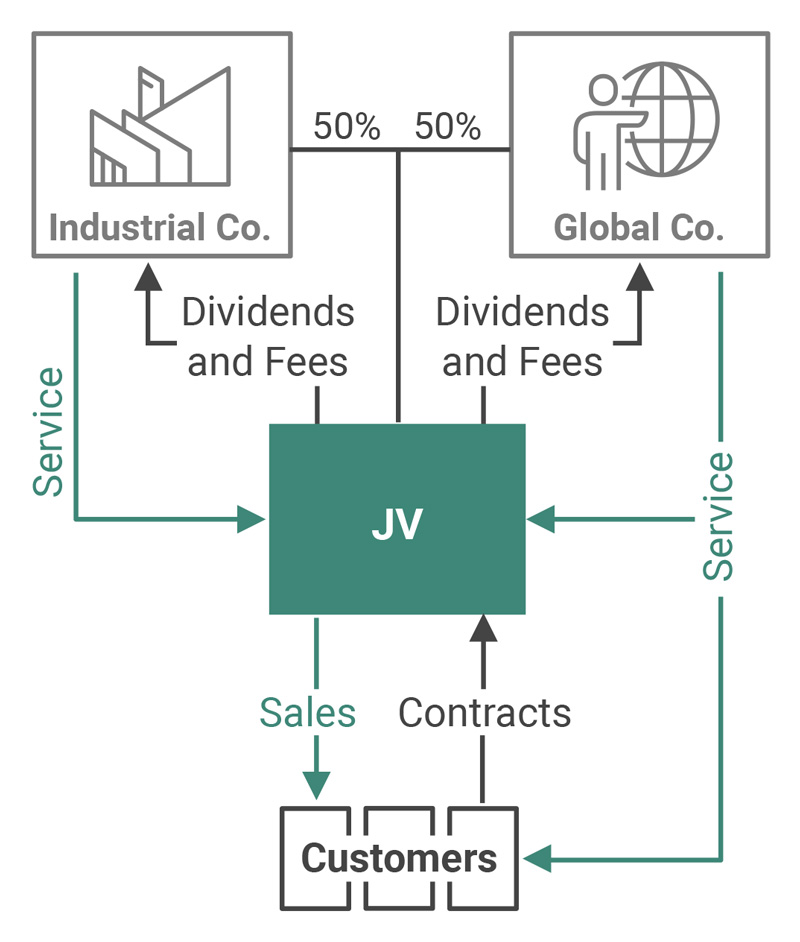

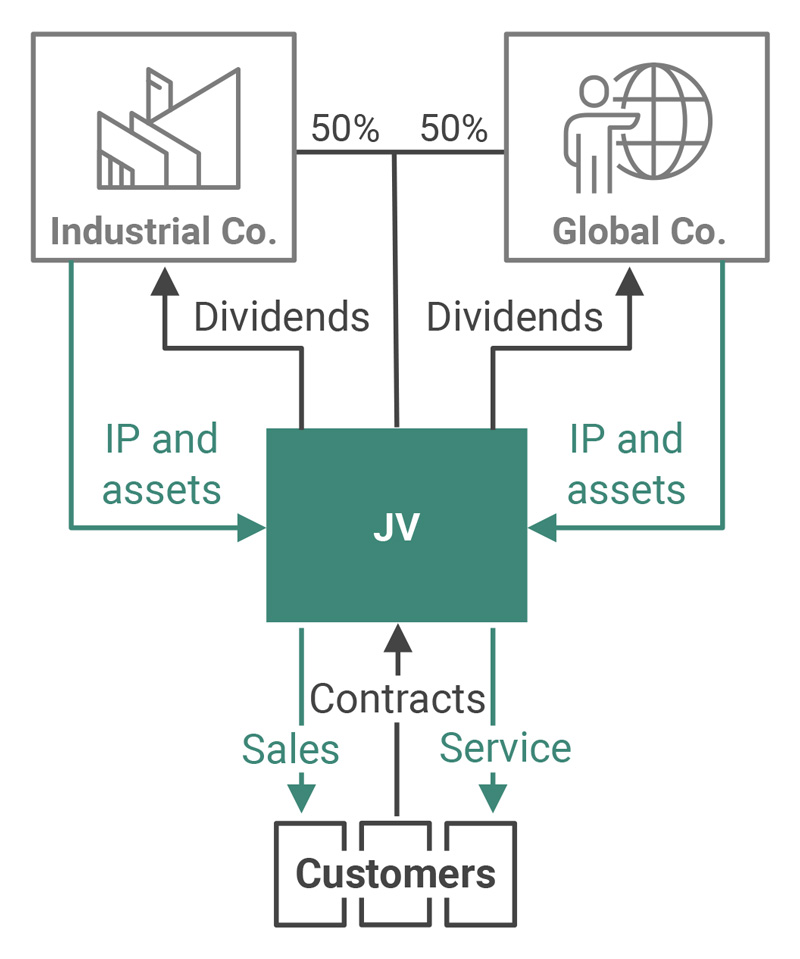

Its preferred partner was a global company that sold a variety of similar products, giving it global channel access but also making it a competitor. Given the complexity of the situation, when the regional company was considering how to partner, rather than locking in on an alliance or a JV, it weighed a series of each (Exhibit 4).

On the one hand, they felt an alliance preserved fundamental ownership of the IP and made it easier to terminate the relationship quickly if sales lagged – a real risk, given that the preferred partner was also a competitor. On the other hand, a joint venture offered tangible equity to help the partner feel ownership of the product and accountability for driving sales – but risked an eventual buyout, given the preferred partner’s greater financial resources and market relationships. It was also possible to choose a hybrid option, starting first with an alliance and then evolving to an equity JV once each partner gained comfort.

Overview:

Pros for Industrial Co:

Cons for Industrial Co:

Overview:

Same concept as Option 1, except for economics:

Pros for Industrial Co:

Cons for Industrial Co:

Overview:

Pros for Industrial Co:

Cons for Industrial Co:

Overview:

Pros for Industrial Co:

Cons for Industrial Co:

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

Alliance Challenges. Not everything is rosy with alliances, as they introduce inherent complexities and risks alongside the aforementioned benefits. It is hard to manage competing strategic interests, which may diverge over time and prematurely rupture the alliance. Economic flows can be complex to value and monitor, leading to disagreements on the split of profit, or royalties due. Despite best efforts, technology may leak out to competitors. The partners may have different metrics or yardsticks for success (e.g., short-term vs. long-term; top-line growth vs. margins), which pull the collaboration in opposite directions. Decision-making may be slow and tortured. Above all else, the partner may cheat, shallowly cooperate, abandon the alliance, or otherwise fail to deliver on their side of the bargain. And the ongoing management of an alliance at the operating level, with a partner that isn’t culturally similar, can be a real challenge.

Alliance End Game. As is true for JVs, it is important to think through the likely endgames of an alliance. Of course, most alliances merit termination if they are not on track to achieve objectives. But termination may also be the right outcome after an alliance has delivered its mission. And, in other cases, alliances are a path to escalate to a joint venture (or, sometimes, a way to test an acquisition target). In fact, our research has shown that some type of non-equity alliance relationship precedes more than half of all JVs. As an example, BP and DuPont formed an alliance to research bio-based butanol, the alliance was set up as a transitory structure that can disappear if promising joint research results in a commercial product. In their case, the biobutanol effort transitioned after the research phase into Butamax, a JV with dedicated assets and staff focused on production and commercialization.

Even when companies have great alliance ideas, many alliances do not succeed. Analysis by Ankura and others indicates success rates of non-equity alliances to be between 30%-60%, with “partial” success – i.e. meeting some but not all targets – somewhat north of 50% on average. While there is no silver bullet to success, our experience has identified a set of keys to excellence across the alliance deal-making process (Exhibit 5).

Alliances typically run into problems when the partners lack a coherent and explainable strategy for the partnership, or when partners are financially weak or otherwise culturally or ethically incompatible. Assuming those two hurdles are cleared, the next challenge is choosing the right structure. Most deal teams kick off this process already thinking the right path is an alliance, a JV, or something else, making it an opportune moment to challenge preconceived notions by considering alternatives.

Keeping an open mind going into deal negotiations is also helpful because the line between a JV and an alliance is often fluid in practice, once you get into structuring. For example, the airline industry often uses “anti-trust immunity” joint ventures to collaboratively set prices and schedules and fully integrate and share economics on key routes – yet these joint ventures lack separate equity entities, even on paper. Or take the case of the North American Coffee Partnership, a Starbucks-Pepsi JV to bottle and sell ready-to-drink coffee in the U.S. This JV has essentially no direct employees, and all work is done inside the parent companies on behalf of the JV – which sounds very similar to the typical highly integrated pharmaceutical co-promotion alliance, except for the existence on paper of a jointly owned entity between Starbucks and Pepsi.

With that in mind – what does it take to negotiate and structure an effective alliance?

Make sure that all sides share the same goals – on expenses, on market share aspirations, on what success looks like, etc. – and are willing to commit on paper. Define explicit expectations of what each side will provide in pursuit of those goals so that partners do not shift resources away. And consider reinforcing that point by making sure the partners are incented directly (e.g., there is a clear path to generating profit for performing alliance work) and seeing if all sides would agree on the concept of performance bonuses and penalties to secure commitment.

For example, in a high-tech industrial sales alliance between an IP holder and a global firm, the global firm agreed to pay an annual license fee on top of a percentage royalty on all revenue. The global firm also received exclusivity in certain markets at the outset, contingent on meeting certain sales targets that ramped over time. Combined, these created a significant incentive (and implied penalty) related to driving sales, making the IP holder more comfortable in handing over exclusive rights to its product.

Key things to focus on include setting up parallelism in the steering structure (i.e. similar levels of seniority); creating “teams” that bridge the two companies’ organizations and systems; creating accountable individuals in key roles (vs. having those done on part-time basis); agreeing on a cadence or forums, reporting; and planning that will sustain momentum, etc.

The most successful deal-makers spend time focusing on the items that could kill an alliance, and often take the following approaches to structuring those terms:

Because an alliance does not result in the creation of a separate jointly owned business, there is a tendency to downplay the importance of governance in the absence of a formal Board. For smaller alliances, highly informal governance using an executive sponsor and a parttime alliance manager from each side can work. But when the alliance is highly valuable, the relationship is complex and interdependent, and there is the potential for significant expansion in the future, formal governance structures are a critical need.

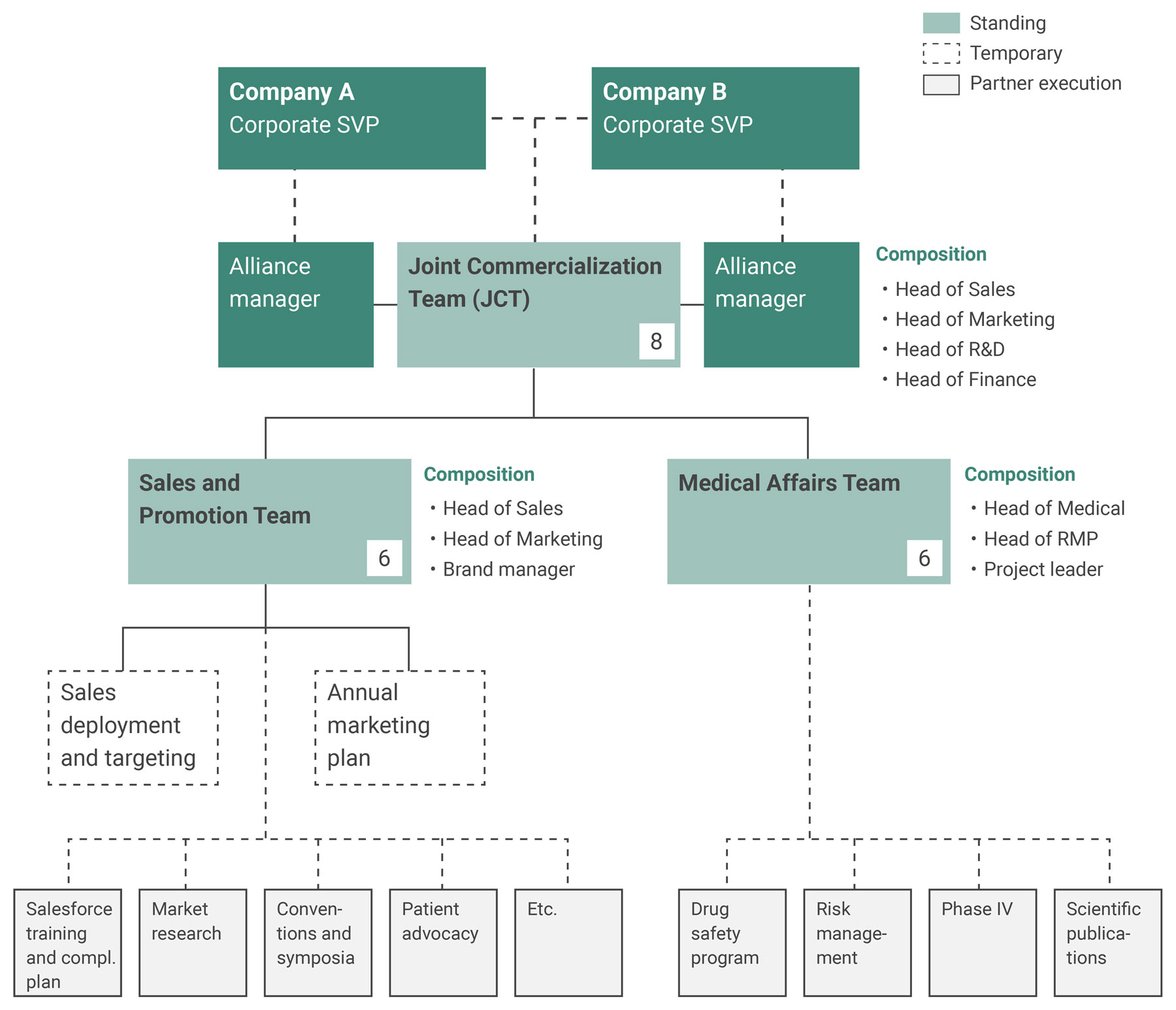

A formal governance structure can help an alliance to meet – and grow beyond – its mandate. In addition to unlocking growth, alliance governance can also be critical for protecting the investment made. When a pharmaceutical company agreed to an alliance to drive final development and commercialization of its most important drug in the U.S., it forced significant up-front investment in defining multiple layers of governance, including key participants and tasks from the most senior level down to day-to-day working teams (Exhibit 8). In the words of their director of strategic alliances, “we were just not going to allow it to wander along without a high degree of oversight and dedicated supervision.”

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved

Connecting back to initial conversations around the goals of the alliance, agree as part of the deal on performance metrics (and targets) that measure success relative to those goals. For each type of goal, alliance partners ought to apply relevant measurements.

Financial types are usually interested in – and good at – measuring returns in the form of short-term cash flows. It is, however, much harder to measure long-term value associated with market positioning or learning. This is a challenge, because many alliances are based on the desire to learn (i.e., improve capabilities) or to improve market positioning. Without appropriate measurements, the alliance’s progress can’t be tracked, adjustments can’t be made, and stakeholders (whether partners, customers, or employees) can’t be motivated.

In the case of a learning alliance, performance metrics might focus on access to new technologies, rights of discovery, improvement in R&D cycle times, effectiveness of knowledge capture, minimization of knowledge leakage, and so on. For example, one emerging market retail alliance agreed on an annual basis to develop a “skills transfer plan,” including goals and metrics that defined success that year.

To reinforce the importance of meeting those metrics, they also agreed to an escalation process that introduced penalties for failure (Exhibit 9).

On the other hand, a marketing alliance could have performance metrics built into the agreement ranging from market share to customer access, insight into customer needs, and product design. Regardless of the type of alliance, the metrics must be tied to its strategic intent, be measurable, and well understood by all sides.

Alliances can be powerful creators of wealth – but come with no guarantee of success. Improving the odds requires a dedication to the art and craft of alliance structuring, which is unlike traditional M&A work. Time spent aligning on strategic goals, getting deal killers – like scope, IP management, and exit – out of the way, investing in governance and shared decision-making, and figuring out how to measure and monitor performance will always pay dividends. How ready are you to negotiate your next alliance?

We understand that succeeding in joint ventures and partnerships requires a blend of hard facts and analysis, with an ability to align partners around a common vision and practical solutions that reflect their different interests and constraints. Our team is composed of strategy consultants, transaction attorneys, and investment bankers with significant experience on joint ventures and partnerships – reflecting the unique skillset required to design and evolve these ventures. We also bring an unrivaled database of deal terms and governance practices in joint ventures and partnerships, as well as proprietary standards, which allow us to benchmark transaction structures and existing ventures, and thus better identify and build alignment around gaps and potential solutions. Contact us to learn more about how we can help you.