[Infographic] Independent Perspectives Prove Effective in Resolving JV Disputes

98% of disputes that have been referred to a dispute review board do not proceed to arbitration or litigation.

The many commercial relationships between a JV and its parents can cause JV partners to butt heads. Here’s our advice on how you can design these relationships to keep the peace.

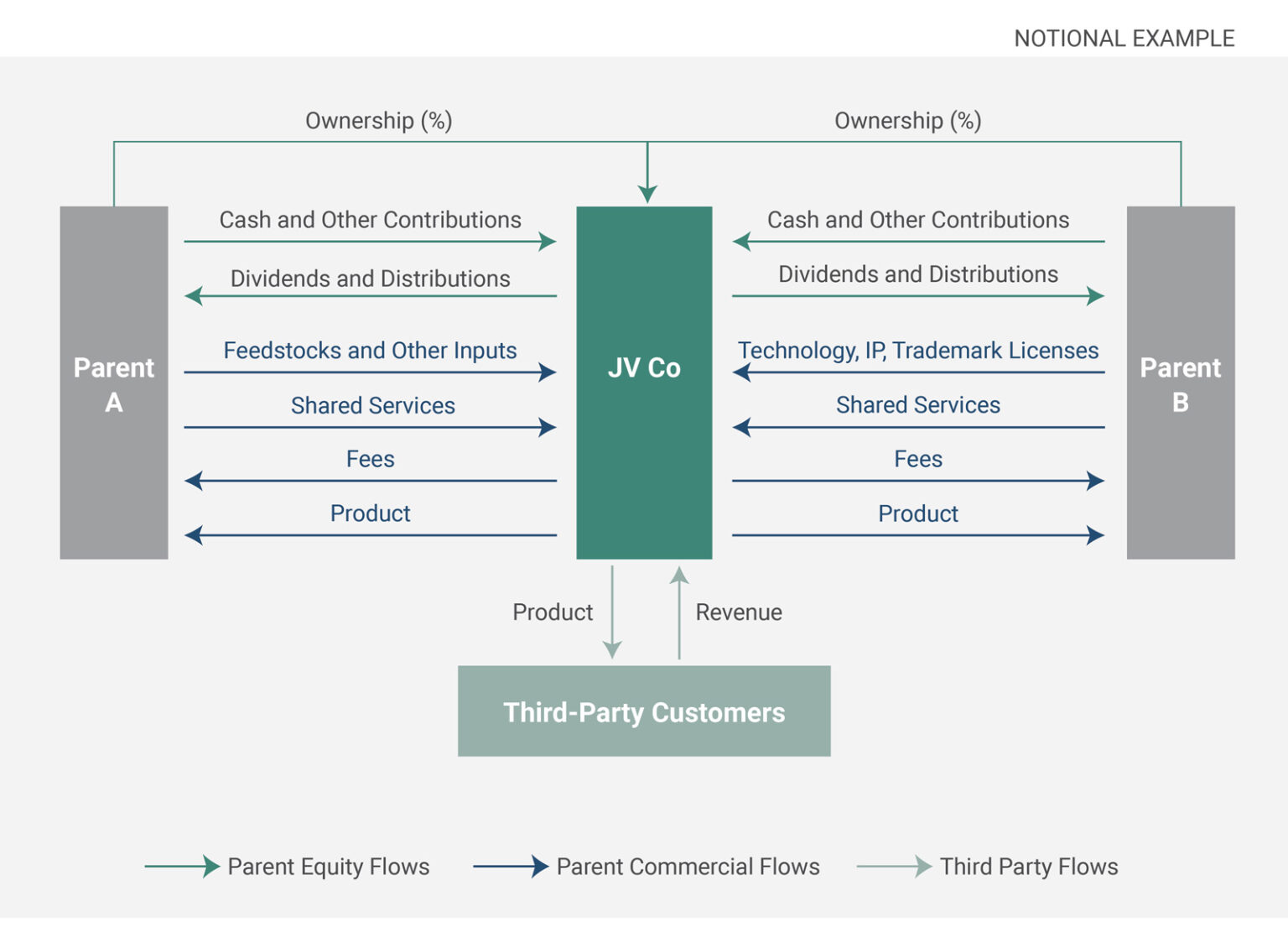

MARCH 2022 — Most joint ventures and their parent companies are co-dependent. Quite often, JVs rely on their parent companies for the supply of components, technology, brands, other intellectual property, business services, people, and/or financing, as well as for access to, or use of, parent-owned assets, such as land or infrastructure, and/or for the purchase of JV products and services (Exhibit 1).

"*" indicates required fields

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

Consider Sadara, a 65:35 JV formed in 2011 between Saudi Aramco and Dow that is the world’s largest single-phase chemical complex. The JV receives its feedstock and other site services, such as utilities, water, and electricity, from Saudi Aramco or its affiliates while relying on Dow for technology licenses, technical services such as catalyst procurement, subject matter expert support, and international marketing services.

Or consider a 50:50 JV between Molson Coors and Yuengling, the oldest beer maker in the U.S. The JV, formed in 2020, aims to bring iconic Yuengling beers, which are currently only sold in the eastern half of the U.S., into new markets by leveraging Molson Coors production facilities and distribution channels. Under the terms of the agreement, Molson Coors will provide certain services to the JV and will purchase beer produced by the JV under a supply agreement.[1]See Coors 10-Q for period ending September 30, 2020 (filed 10/29/20)

Whenever there are commercial relationships between a JV and its parent companies – as in Sadara and the Molson Coors-Yuengling JV – the JV and parent memorialize such arrangements in an agreement. These agreements include pricing terms, which may require partners to navigate a minefield of disagreements and regulatory issues.

Negotiating this affiliated-party price can be the cause of much consternation among partners for several reasons.

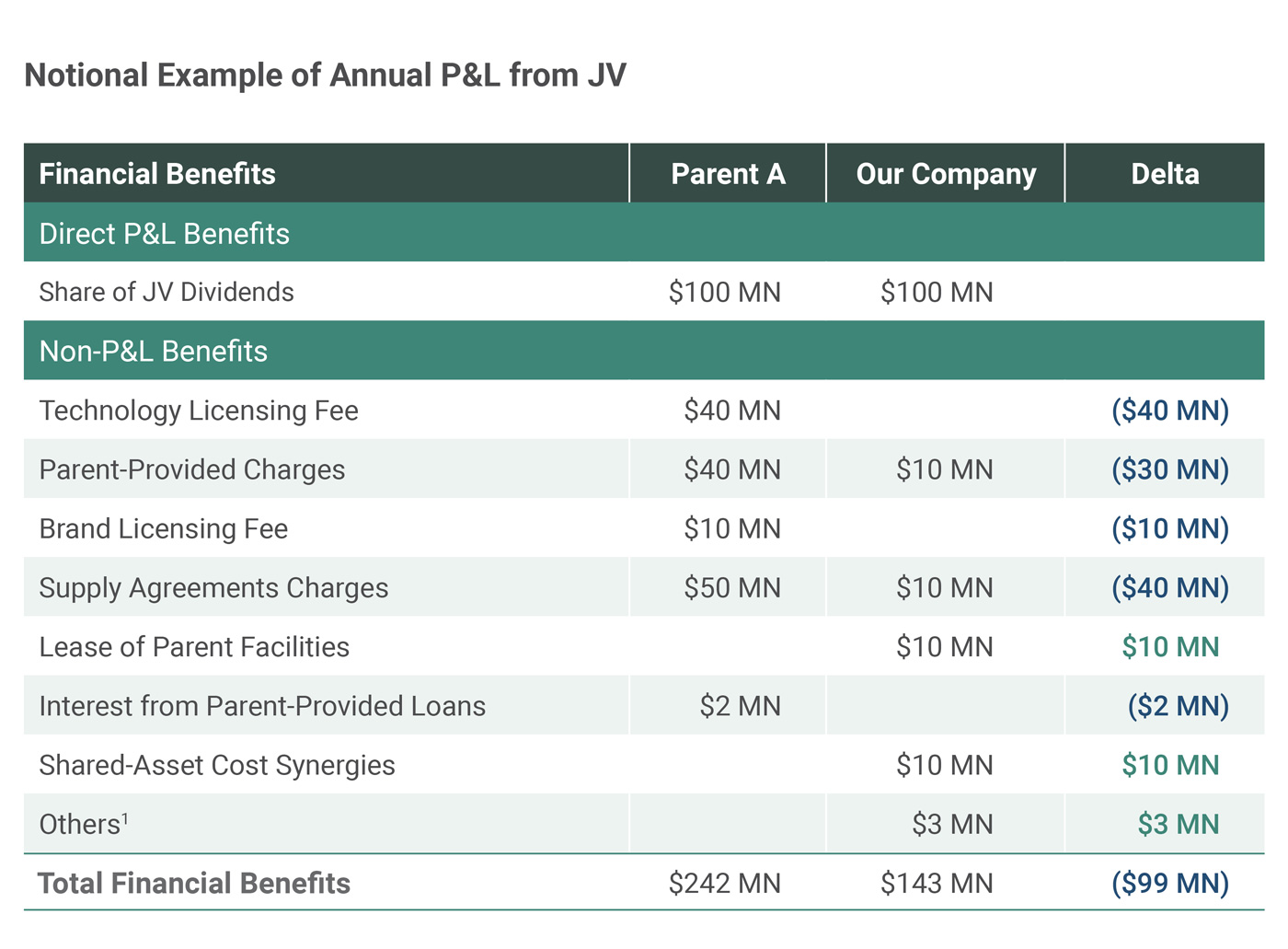

Affiliated-party agreements typically confer unequal benefits and risks on the partners. For partners not buying from or selling to the JV, payments to or from affiliated parties can dilute JV profits and, in turn, those partners’ returns from the JV. By contrast, owner(s) buying from or selling to the JV receive returns from the JV in proportion to their ownership interest in addition to “off JV P&L” returns associated with these flows (Exhibit 2). This poses an inherent conflict of interest: The buying or selling parent has an incentive to sell to the JV at a premium and purchase from the JV at a discount to maximize its total returns from the JV. In contrast, the JV (and other partners through their ownership in the JV) has an opposing incentive: to purchase from the selling parent at a discount and sell to the buying parent at a premium.

1 Examples of other benefits include: (1) earnings from JV pull-through sales of parent products and † -selling/bundling with JV products; (2) financial re-engineering benefits to parent (e.g., de-leveraged balance sheet, capex avoidance, reduction in inventory due to JV presence, reduction in working capital); (3) value from broader relationship with other shareholder(s) developed through JV relationship

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

The same applies to risk. For example, say the price for a JV to purchase a component from a parent is fixed: the JV is required to buy from the partner, and the partner must sell to the JV. In this situation, the JV bears the risk that market prices for the component go down, and it could purchase the component from elsewhere in the market for less but cannot do so. By contrast, the parent bears the risk that market prices increase, and it could sell to another party at a premium, but it is prevented from doing so under the terms of its agreement with the JV. Thus JV-parent transactions inherently put the JV and the relevant partner at odds with respect to benefits and risks related to the price of such transactions.

Parties often are misaligned regarding whether the transaction between the JV and parent is a full or partial contribution to the JV or an arm’s-length commercial arrangement. If a contribution, presumably the JV would not pay cash for the relevant parent-provided product or service. Instead, the parent would receive additional equity in the JV as “payment” for services or products. While rarely the model selected by partners, this is an option and often one that creates confusion among potential JV partners. On the other extreme, the arrangement may be on completely arm’s-length terms, as if the JV and parent were not related. This is a common approach used by partners in some industries, such as mining, and is the approach required by U.S. law in certain situations (e.g., if a controlling partner is a U.S. taxpayer providing the relevant product or service to the JV in the U.S.). The third option is a hybrid of these two, namely that the product or service is provided to the JV at something less than market rates such as on a cost basis. In some instances, the discount to market is deemed an up-front, in-kind contribution to the JV that gives the provider additional equity in the JV on day one. However, more commonly, there may be a discount to market, but that discount is not deemed a formal contribution to the JV and does not provide the partner with increased ownership in the venture. Figuring out which of these buckets a particular JV-parent transaction falls into – namely a 100% contribution, a partial contribution for some increased ownership, a discount for no increase in ownership, or an arms-length relationship – can be complex and require partners to reflect on what is fair in the particular circumstances.

Many affiliated-party transactions entail products or services that lack a true market. For example, how should parties price a license for a JV to use parent technology the parent does not license in the open market? Or how should they value a lease for land that a parent is leasing to the JV and already has required regulatory permits for the JV’s business? When an easily identifiable market price is elusive, parties can become paralyzed by the number or range of pricing options or can come to different conclusions on what is “fair.” In either case, the price can derail or slow negotiations.

Setting such prices requires an analysis, typically by tax or accounting professionals, about whether the JV-parent transaction must comply with transfer pricing regulations: requirements that apply in transactions between commonly owned or controlled entities and seek to impose arm’s-length terms in these transactions. Such rules are intended to prevent companies from shifting profits to lower-tax jurisdictions or outside the corporate family. These rules vary by jurisdiction, but generally, law requires U.S. taxpayers who control a JV (through voting rights or otherwise) to comply with transfer pricing rules.

Setting even a single JV-parent transaction price requires partners to overcome each of these hurdles. Such challenges multiply if there are many JV-parent transactions, as is the case with Sadara. In our experience, pricing and terms of JV-parent relationships may be some of the last terms to be locked down in JV discussions, even if they are fundamental to the deal.

So how can potential JV partners tackle this pricing challenge? The purpose of this article is to provide an overview of the variety of potential pricing options for such arrangements, define key criteria for assessing such options, and illustrate a process parent companies can use to negotiate such arrangements.

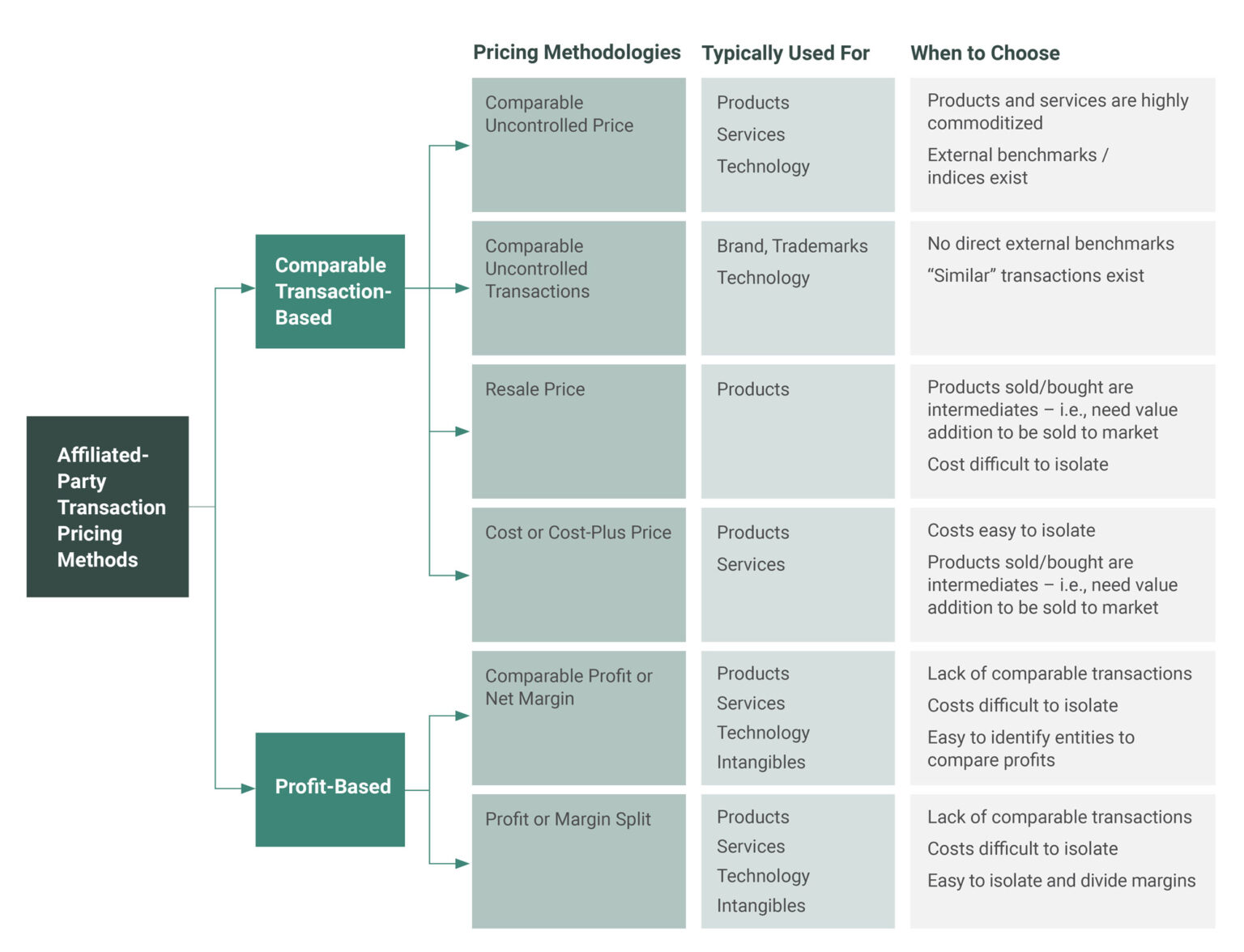

The appropriate price for a JV-parent transaction should depend on the individual characteristics of the venture, as well as the nature of the product, service, technology, or asset provided. Most affiliated-party prices are based on a defensible methodology, which likely includes a comparison, either directly or indirectly, with the price, profit, cost, or margin of a comparable transaction. Typically, such choices fall under one of two categories (Exhibit 3): comparable transaction-based or profit-based.

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

This method is used to determine prices by leveraging a precedent transaction – i.e., using identifiable market prices, a similar transaction for brand/trademarks, costs, or sales price benchmarks. These methods include:

This method helps determine prices by backtracking from the profits generated from the transaction, either by setting the price in a manner that helps the transacting entities realize a fixed margin (comparable to entities in the same industry) or by splitting profits between the transacting entities based on a defensible methodology. These methods include:

There can be many methodologies and options within each of these pricing regimes. For example, some comparable prices are public and widely available such as commodity prices. But even these require some additional analysis – for example, what source should be referenced and when as well as other terms of the arrangement such as the duration of the agreement. And for products or services that have a market comparable, but one that is not fully transparent, industry analysis or other analyses must be conducted to determine a price.

However, determining a price for items without clear comparable prices, such as certain intangibles or unique assets or products, may be even more complex as parties will need to look to alternative pricing regimes or market proxies for the relevant item. Is there a product with a market price that is somewhat analogous to the item at hand such that the market price for the product could be used as a proxy (with a discount or premium to such price as appropriate)? Are the costs for the product known and the price is appropriate? Or is some other approach preferable?

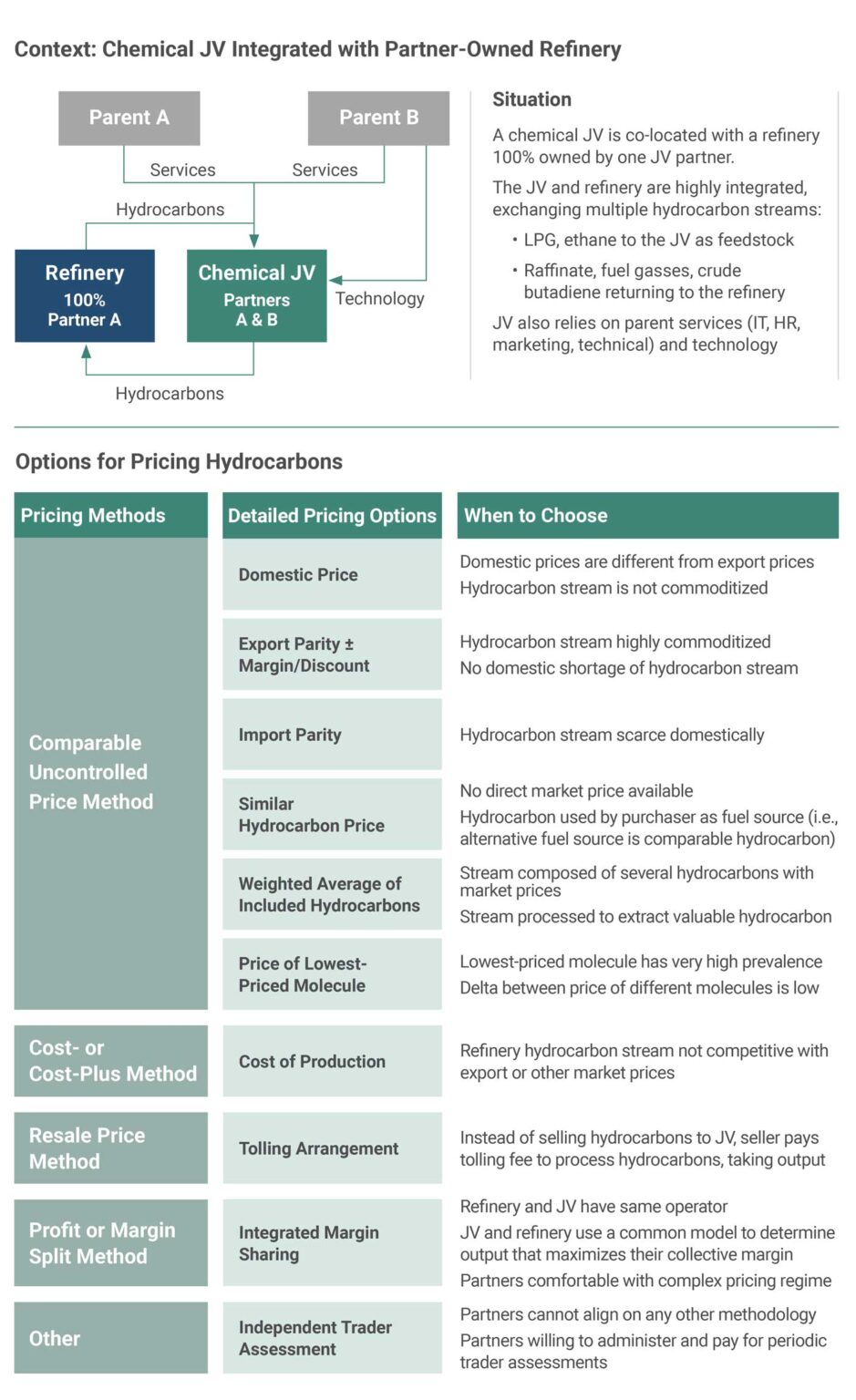

What methodology makes the most sense for a particular product or service will depend on a number of factors, including the type of product or service (i.e., commodity or specialized), the opportunity cost for the seller, and/or the replacement cost for the purchaser (Exhibit 4). The price for the JV-parent transaction is typically at or lower than the price the purchaser could obtain in the market (i.e., the purchaser’s replacement cost); otherwise, the purchaser may elect to buy elsewhere. Similarly, the price is typically higher than the price the seller would receive for selling into the market (i.e., the seller’s opportunity cost); otherwise, the seller would sell into the market. These generalizations, however, may not be universally applicable, particularly for larger transactions involving highly valuable rights or products due to the complexity of the comparable risks of the seller or purchaser. For instance, a partner may be willing to buy or sell at a discount in order to receive favorable terms other than price, a guaranteed supply, or other nonmonetary benefits. The options for JV-parent transaction prices should be determined for each individual item to be priced since the approach for one product or service – say electricity purchased from a partner – may not be appropriate for another – say IP purchased from a partner.

© Ankura. All Rights Reserved.

Once a parent company has identified one or more options for pricing a JV-parent transaction, they should assess such options using the following criteria:

JV-parent commercial relationships, including their pricing, are inherently plagued by conflicts of interest. Unlike other non-affiliated-party JV transactions where JV partners’ incentives are aligned to get the best deal for the JV, in a JV-partner transaction, the parent involved is no longer looking out for solely the best interests of the JV, but instead its cumulative interests as an owner in the JV and as party to the transaction.[2]This inherent conflict of interest can be particularly problematic for JV board members appointed by the parent company that will be party to a JV-parent contract. See “JV Directors Duty of … Continue reading These transactions unavoidably “divide the pie” between the JV and the applicable partner, causing tension about where the line should be drawn between the parent’s finances and the JV’s. This inherent conflict of interest tends to be first and foremost in the minds of partners negotiating affiliated-party prices. Parents should ensure prices are set in a manner that minimizes this conflict to the extent possible and creates a “fair” allocation of benefits and risks from the perspective of the JV and parent alike. Partners should also consider including mechanisms in JV-parent contracts or other JV agreements to manage these conflicts such as a requirement that non-conflicted partners approve JV-parent contracts, caps, and floors on prices; a right to renegotiate price under certain circumstances; or a requirement the price be within a certain percent of a benchmark price.

Parent companies should determine whether JV-parent transactions are subject to transfer tax rules, which will depend on the applicable parent’s ownership and control over the JV and the jurisdictions involved. Transfer-pricing rules are in place to prevent a JV partner, typically one with 50% or more ownership in the JV or control over the JV, from shifting profits from a high-tax jurisdiction to a subsidiary or controlled entity (including a JV) in a lower-tax jurisdiction. To prevent such arbitrage, tax authorities require transfers among affiliates to be on arm’s-length terms. While there is flexibility in what is considered “arm’s length,” JV partners should be aware that if transfer tax rules apply, pricing of JV-parent transactions will receive additional scrutiny, and the partners should work with tax and accounting professionals to ensure the partners’ selected price construct will not have unintended tax consequences.

Potential JV partners should also look forward to the administration and governance of the relevant related-party agreement. Some agreement terms require little or no ongoing attention. For example, prices for products pegged to an international index require little monitoring or recalibration, and long-term related-party agreements do not require frequent renegotiation. By contrast, other JV-parent agreement terms require constant or frequent attention. For instance, services provided at cost require the service provider to track costs and the service recipient to have audit and review rights to ensure costs are not inflated.[3]In some cases, antitrust laws may prohibit JV partners from sharing information, including potentially information related to affiliated-party transactions. See “Managing Competitively Sensitive … Continue reading Similarly, related-party agreements with short durations require frequent renegotiation and approval by the board or shareholders. Such administration and governance costs can drain JV management, JV board, and parent company attention and resources. Say the parties agree a third-party expert will determine the value of a particular component provided by the JV on an annual basis. Hiring, providing information to, and managing such an expert could be time-consuming and expensive. Parties should assess the future administrative burden and costs of various pricing options.

Partners should also assess how pricing constructs will play out over time. Are prices dynamic, changing with the market? Or, if prices are fixed, for how many years does the price stay constant? How do prices or JV-parent arrangements more generally change if there is a change in macroeconomic, market, or JV circumstances? And what will happen with respect to the JV-parent relationship if one or more parents exits the JV down the road?[4]See “Split Ends: How to Exit a JV by Untangling the Assets,” Lois D’Costa, James Bamford, Josh Kwicinski, The JV Deal Exchange, October 2016.

Partners should not only pay attention to the top-line price but also to other terms in JV-parent agreements to assess how such arrangements will play out in the longer term.

These assessment criteria can help JV partners identify and mitigate the pitfalls of various pricing options. However, merely developing JV pricing options and assessing them using this qualitative criteria is insufficient to identify and set the prices and terms for the many JV-parent transactions that help JVs function. In fact, this is just one step in a broader process.

The full process for identifying and setting JV-parent transaction prices starts before developing pricing options, when partners determine the scope of the JV and its relationship to its owners. The process continues until each related-party price is locked in and codified in an agreement (Exhibit 5). In between these bookends, partners identify pricing options, conduct financial and nonfinancial assessments, and negotiate for their preferred approach.

This process begins with defining the scope of the joint venture. The number, type, and materiality of JV-parent commercial relationships is highly tied to JV scope and the overall construct for the deal. For example, the JV may have a narrow scope of solely producing (not marketing) products, which are then marketed by one or more parents. In such a case, there may be a JV-parent transaction related to the parent providing marketing services to the JV. Or, the JV may have a broader scope – say producing and marketing its own products – in which case a JV-parent marketing agreement is not required. As the shape of the deal morphs, so do the number and nature of JV-parent transactions. Only after JV partners determine what JV-parent transactions are needed will they begin the process of pricing and negotiating the terms of such transactions.

Once the number and type of related-party transactions have been identified, a JV partner should individually identify the relevant pricing options for that transaction, taking into consideration the specific nature of the product or service exchanged and the overall purpose and model for the venture. As discussed above, in some situations, there will be a clear benchmark or price that is natural given the circumstances. In other cases, this requires more creativity and broader thinking.

Following the development of pricing options, the partner should individually assess these options qualitatively and quantitatively. Qualitative evaluations should involve a review against the four criteria discussed above, namely (1) ability to minimize inherent conflicts of interest, (2) compliance with applicable regulatory restrictions, (3) ease of administration and governance, and (4) long-term sustainability of the pricing option.

Quantitative assessment is also critically important at this juncture. A potential JV partner should develop models showing the impact of different pricing scenarios on such a partner’s bottom line, both at the parent company level and at the JV level.[5]See “Assessing Total Joint Venture Economics,” The Joint Venture Exchange, November 2008. These models should be dynamic so the partner can adjust pricing options and other assumptions and see the impact of different pricing options. In addition to testing pricing options using the model, a potential JV partner should use the model to test sensitivities and engage in scenario planning. What happens if the demand for the JV’s products is less than expected? What if the price for a key JV input increases? How do these changes affect JV-partner transaction prices, if at all? Thinking of future scenarios and how affiliated-party transaction prices would or would not change can help partners clarify those prices they are willing or not willing to accept.

Putting together the qualitative and quantitative assessments, the partners should align internally on their preferred pricing option as well as one or more fallbacks.

Armed with the knowledge from these qualitative and quantitative assessments, potential JV partners should then step up to the negotiating table to aim to convince their partners that their preferred approach is the best or most appropriate approach. Partners should seek to agree on a pricing option at a high level (e.g., domestic market prices) for each commercial relationship between the JV and a parent. Once a high-level option seems acceptable to both partners, the partners can dig into the details for the commercial arrangement. Such details may include what market index will be used as a reference or whether the parent must provide most favored nation pricing to the JV. Or they may relate to other terms of the commercial agreement. What is the duration of the pricing arrangement? Will there be minimum quantities required to be purchased? Are there caps on the price? Or a collar setting a minimum or maximum price? Do any systems or processes need to be put in place to administer or govern the JV-parent transaction?

Throughout negotiations, JV partners should be plugging various proposed prices into their dynamic model to assess the likely impact of such prices and adjust reaction to a proposed price accordingly. Similarly, they should be assessing various approaches against qualitative criteria. In addition, JV partners should consult tax and accounting counsel, preferably early in the process, to ensure price options being discussed do not have unintended tax consequences given applicable tax and accounting rules, including transfer pricing laws.

Negotiations may reveal that a commercial relationship between the JV and a parent is not the most economical or favored approach. In such cases, negotiations can change the overall deal construct, perhaps causing the JV to acquire a particular product or service from the market as opposed to a partner or cause the JV to bring certain activities in-house.

After one or potentially many iterations of negotiations, partners will coalesce around a preferred pricing construct for a JV-parent transaction. We recommend tentatively agreeing to such prices for each individual commercial arrangement. However, only lock in any individual material price once all material prices have been negotiated. Such an approach may allow a partner to accept an unfavorable price in one area – say the amount of a lease from the partner to the JV – if it receives a favorable transfer price in another area – say the price for the other partner to supply the JV with a component – that more than offsets the unfavorable price. This approach provides more flexibility when different partners have divergent expectations for particular transfer prices.

Joint ventures almost always involve some sort of ongoing commercial relationship between the JV and one or more parent companies. These agreements, in some cases, are critical to the JV’s success, or the success of a parent company. JV partners looking to negotiate the price of these arrangements can find themselves overwhelmed, particularly when there are many different JV-parent transactions that collectively determine JV economics and how “good” the deal is for the parent companies. But if dealmakers understand key considerations about related-party transactions, develop and analyze a range of potential options, and negotiate in good faith to find a mutually agreeable package of related-party transaction prices, they can create a JV that is set up for success – and that sets the parent companies up for success too.

James Bamford is a Senior Managing Director, Tracy Branding Pyle is a Managing Director, and Shishir Bhargava is a Senior Director in Ankura’s Transactions Practice, where they advise clients on joint venture and partnership strategy, transactions, governance, and restructuring.

We understand that succeeding in joint ventures and partnerships requires a blend of hard facts and analysis, with an ability to align partners around a common vision and practical solutions that reflect their different interests and constraints. Our team is composed of strategy consultants, transaction attorneys, and investment bankers with significant experience on joint ventures and partnerships – reflecting the unique skillset required to design and evolve these ventures. We also bring an unrivaled database of deal terms and governance practices in joint ventures and partnerships, as well as proprietary standards, which allow us to benchmark transaction structures and existing ventures, and thus better identify and build alignment around gaps and potential solutions. Contact us to learn more about how we can help you.